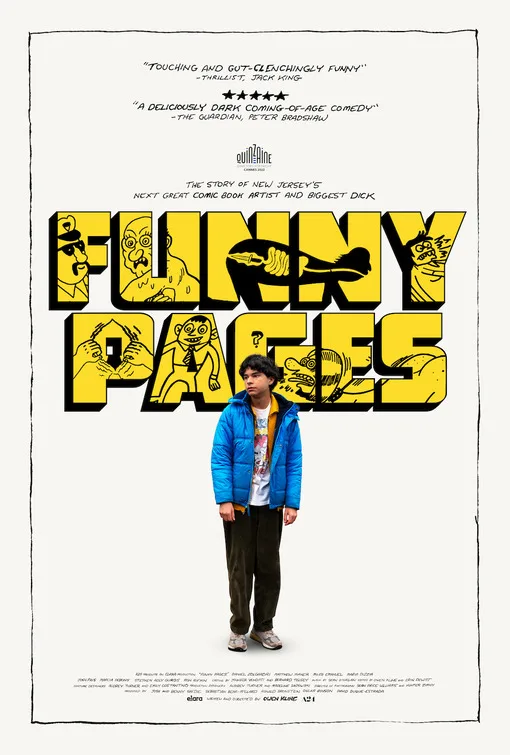

“Funny Pages” has a startlingly anti-inspirational attitude, while still being wrapped in the trappings of an inspirational movie. There’s a lot of pressure for narratives to assume certain forms: be inspiring, encourage self-empowerment, bask in the glow of a young person stepping into their own light, etc. “Funny Pages” sticks to its grim guns. All of the “inspirational” aspects are present in the film as ideas and concepts, perhaps even expectations since we absorb the lessons from “media,” but there’s an underbelly to those concepts, and the underbelly is the reality. I suppose it will depend on your worldview how “Funny Pages” will land. I personally find it refreshing, astonishing (in parts) even. “Funny Pages”‘ obvious antecedent is a movie like “Ghost World,” but it’s more like a teenage “Five Easy Pieces,” packaged in a coming-of-age narrative. This is Owen Kline’s first feature, and he knows this world—the world of comic book obsessives and hopeful comics artists—very well. Nostalgia is probably at work in the film—somewhere—but it’s buried under layers of grime and bitter disillusionment.

The movie hits the ground running. In the first scene, Robert (Daniel Zolghadri), a high school senior, sits in the office of his art teacher, an enthusiastic and messy Mr. Katano (Stephen Adly Guirgis). Katano is giving Robert an inspirational speech: he wants Robert to give up college and/or art school and start trying to get his work published as soon as possible. Send stuff out, get a portfolio together, and remember to always “subvert everything.” Robert’s work is profane (understatement), with grotesque women heaving gigantic bosoms, performing graphic sexual acts, in a wink-wink style, a crude version of Robert Crumb’s work. It’s clear Robert’s influences (maybe too clear?), and Katano is a big fan. He puts Robert to the test: he wants Robert to draw him on the spot, so he strips down to his socks and stands on his desk, displaying his big belly and everything below it, demanding Robert begin the sketch. Robert seems unfazed by this. To re-cap: Mr. Katano is a high school teacher.

This scene encapsulates “Funny Pages”‘ sneaky approach. On the surface, Katano seems like a good mentor. He’s encouraging, he believes in the kid, darn it! But then the mood changes. Is Katano a predator? Should we be alarmed? Katano dies suddenly, and Robert breaks into the school to “rescue” Katano’s artwork, and is arrested in the process. After the debacle dies down, Robert follows Katano’s advice, and drops out of high school, shocking his parents (Josh Pais and Maria Dizzia). Robert moves out on his own, and devotes himself—sort of—to pursuing his dream. (This reminds me of a line from Mike O’Malley’s “Certainty” [I should disclose that Mike is my first cousin]: a character, cranky about his wife’s out-of-the-blue desire to be a professional actress, grumbles, “Unfortunately, no one’s ever written a book that said ‘Don’t follow your dreams.'”)

The apartment Robert finds is in the frighteningly dilapidated Trenton, NJ, and it’s not even an apartment, but a couch in an illegal basement sublet, shared with two other men, the balding fussy Barry (Michael Townsend Wright), and his friend (it’s not quite clear the relationship) Steven (Cleveland Thomas Jr.). The two much older men share space and swap obscure cultural references, like the ups and downs of Paul Lynde’s career. This disgusting basement space is filmed with such vivid detail that a steamy hot stench emanates off the screen. The murky fish tank glows a mottled green: the fish are long dead. Everyone is drenched in sweat. There are no windows. Meanwhile, Robert gets a job working for the public defender who represented him in the Katano break-in case. This is Cheryl (Marcia DeBonis), who takes pity on the hapless boy who asks her if the court needs a sketch artist. She puts him to work typing down everything everyone says who comes into her office. Cheryl giggles at everything Robert says, and calls him “adorable.” It’s impossible to avoid the feeling that she’s projecting.

In a coincidence that strains the plotline to its breaking point, Wallace (Matthew Maher) barges into her office, looking for representation after being arrested for causing some sort of ruckus at a local Rite Aid. In the process of their initial conversation, Wallace mentions he once worked as a color separator (not a colorist, an important distinction) for a reputable comics publisher. To the opportunistic Robert, Wallace might be a “way in,” so he pursues Wallace as another possible mentor. This choice turns out to be catastrophic, another way “Funny Pages” follows Mr. Katano’s initial advice to “subvert everything.” Wallace is unpredictable, paranoid, violent, and totally unstable.

“Funny Pages” unfolds as almost a picaresque narrative, Robert tripping in and out of different environments, episodic, at times funny, at times not. There’s the comic book store where Robert hangs out, populated by unsmiling murmuring obsessives, the upscale Princeton home where Robert grew up, and the sublet-basement which looms over everything. Even Robert’s prickly friendship with another artist-hopeful named Miles (Miles Emanuel) is seen as episodic, rather than something stable. Miles is sweet and open, and Robert seems to only tolerate him because he can lord his own talent over Miles’ seeming lack of talent. Robert is a purist: he cares most about form. Miles cares about soul. Robert is not a good friend to Miles, but Miles is the only game in town. It takes a while to realize that Robert lives in almost total isolation. He has no other friends. He has no love interest, male or female. Wallace is the object of all his attention.

In another director’s hands, “Funny Pages” would be the story of a young isolated boy integrating himself into society: he eventually makes up with his parents, embraces Miles, and gets a shot at the big-time through Wallace. But here, down to the final shot, a subversion of the final shot of “Call Me By Your Name,” there’s a sense of emptiness and futility.

There are a couple of cameos by beloved character actors, namely Ron Rifkin as Robert’s housebound grandfather confused about the remote control, and Louise Lasser, an opiate addict, confined to a wheelchair, demanding Robert try to get her some Percocet from behind the pharmacy counter. These are one-offs, but their presence lingers. They are residents of a wider world, a world Robert passes through, while barely comprehending it, or caring to comprehend it.

I was first introduced to Matthew Maher’s work when I attended Annie Baker’s Pulitzer-Prize winning The Flick at the Barrow Street Theatre. Maher played one of the two ushers at a movie theatre in Worcester, Massachusetts, and his work was so resonant with buried anger and self-pity, but also a sense of moral righteousness, perhaps misguided, perhaps not, a sense that he was willing to go to the mat for what he thought was right. Maher is sometimes an uneasy presence, and this is in his favor. His performance in “Funny Pages” is key. Wallace’s presence in the narrative may be due to a coincidence that beggars belief, but he reveals the character’s nature right off the bat, and allows us the space to catch up.

Two cinematographers are listed in the credits—Sean Price Williams and Hunter Zimny—so it’s not clear who did what. The film doesn’t have a discernible visual style. (Whoever shot those basement sequences, however, deserves an award. The grossness is visceral.) Zimny doesn’t have much of a track record yet, unlike Sean Price Williams, one of the most gifted cinematographers working today. He shot the beautiful melancholy “Christmas, Again,” the jittery street-drama “Heaven Knows What,” “Queen of Earth” (and all of Alex Ross Perry’s films), as well as the Safdie brothers’ impressive “Good Time” (the Safdie’s produced “Funny Pages”). At a recent Bushwick-based film festival hosted by the artists’ collective AdultFilm, a short film called “Let’s Get Lost,” directed by Sam Stillman, was included in the program. Some of the images were of such swooning dreamy beauty I waited for the cinematographer credit at the end. It was Sean Price Williams. He’s a major talent. “Funny Pages” is, like its message, anti-beauty. Perhaps the visual approach was a conscious way to avoid nostalgia.

Kline makes an admirable attempt to refuse sentimentality a place at the table. But the ending feels unfinished, almost like it stops in mid-sentence. There’s “unfinished” like the haunting final shot of “Five Easy Pieces”—one of the best in cinema—where the landscape envelops the characters in nothingness, all of those 18-wheelers headed to nowhere, leaving from nowhere. What about the woman left behind? Where will she go? At the heart of these questions is a windy abyss of meaninglessness. “Funny Pages” tiptoes into the periphery of this kind of exploration, but falls short in sticking the landing.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.