Strange, how a man once so reviled has gained stature in the memory. How we cheered when Richard M. Nixon resigned the presidency! How dramatic it was when David Frost cornered him on TV and presided over the humiliating confession that he had stonewalled for three years. And yet how much more intelligent, thoughtful and, well, presidential, he now seems, compared to the occupant of the office from 2001 to 2009.

Nixon was thought to have been destroyed by Watergate and interred by the Frost interviews. But wouldn’t you trade him in a second for Bush?

The confession wrung out of him by Frost acted as a catharsis. He admitted what everyone already knew, and that freed him to get on with things, to end his limbo in San Clemente, Calif., to give other interviews, to write books, to be consulted as an elder statesman. Indeed, to show his face in public.

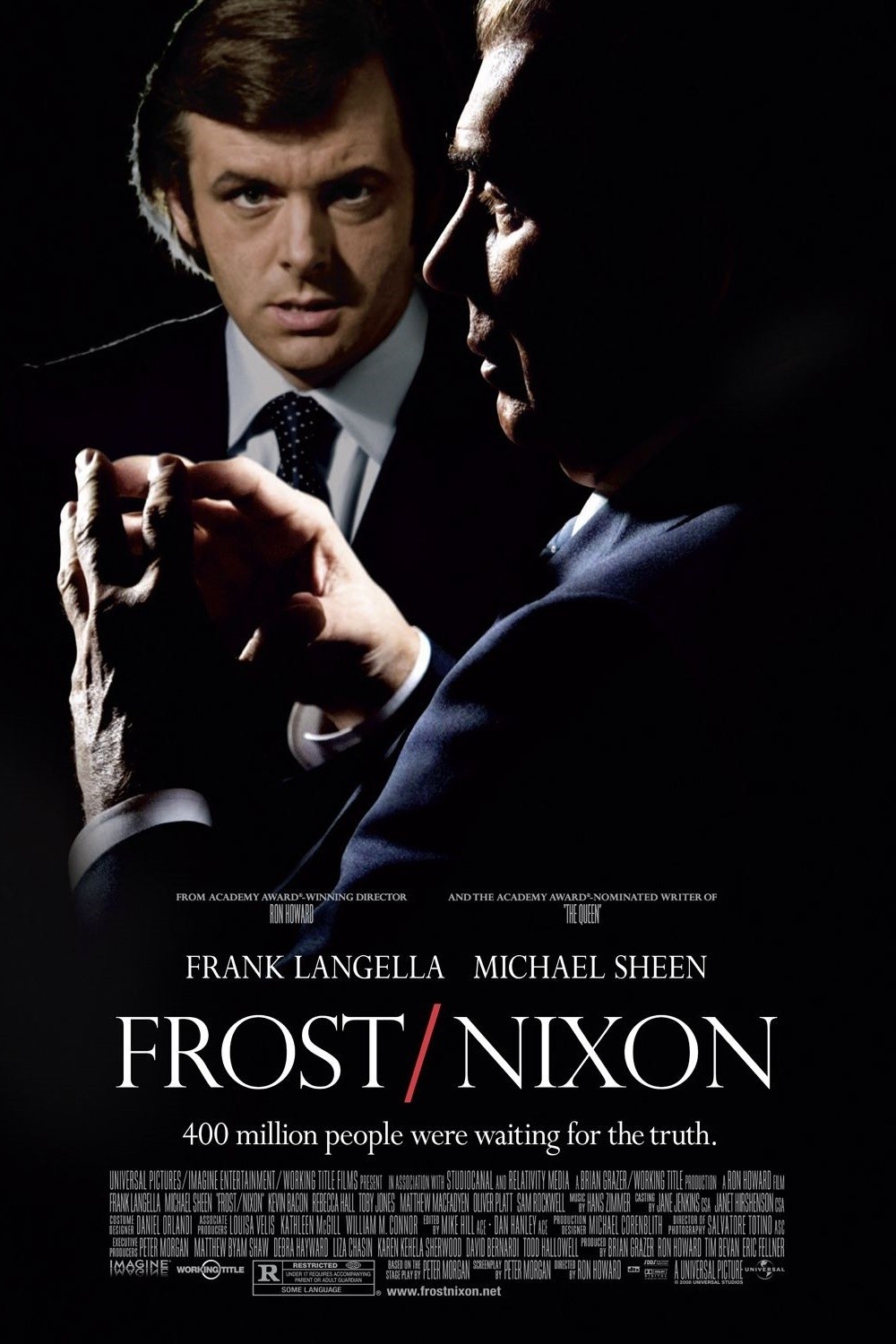

Ron Howard’s “Frost/Nixon” is a somewhat fictionalized version of the famous 1977 interviews, all the more effective in taking the point of view of the outsider, the “lightweight” celebrity interviewer, then in his own exile in Australia. Precisely because David Frost (Michael Sheen) was at a low ebb professionally and had gambled all his money on the interviews, his POV enhances and deepens the shadows around Nixon (Frank Langella). This story could not have been told from Nixon’s POV because we would not have cared about Frost.

The film begins as a fascinating inside look at the TV news business and then tightens into a spellbinding thriller. Early, apparently inconsequential scenes (Frost as a “TV star,” Frost picking up a woman on an airplane, Frost partying) are crucial in establishing his starting point. He was scorned at the time for even presuming to interview Nixon. He won the interview for two reasons: He paid the ex-president $600,000 from mostly his own money, and he was viewed by Nixon and his advisers as a lightweight pushover.

And so he seems during the early stages of the interviews (the chronology has been much foreshortened for dramatic purposes). He sidetracks Frost, embarks on endless digressions, evades points, falls back on windy anecdotes. Frost’s team grows desperate. Consisting of an experienced TV newsman named Bob Zelnick (Oliver Platt) and a researcher, James Reston Jr. (Sam Rockwell), they implore him to interrupt Nixon, to bear down hard, to keep repeating questions until he gets an answer. Frost was a man accustomed to being nice to Zsa Zsa Gabor. He didn’t have to be nice to Nixon. He had hired Nixon.

I can’t be sure how much of the film’s relationship between the two men is fictionalized. I accept it as a given in the film because this is not a documentary. The screenplay by Peter Morgan is based on his award-winning London and Broadway play, which also starred Langella and Sheen. What Morgan suggests is that even while Nixon was out-fencing Frost, two things were going on deep within his mind: (1) a need to confess, which may have been his buried reason for agreeing to the interviews in the first place, and (2) identification with Frost, and even sympathy for him. Nixon always thought of himself as the underdog, the outsider, the unpopular kid. “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore,” he told the press when his political career apparently ended in his loss of the 1962 California gubernatorial election.

Now look at Frost. Although he had a brilliant early career in England, which Nixon may not have been very familiar with, he is shown in the film as a virtual has-been, exiled to Australia. You can count on Nixon and his agent Swifty Lazar (Toby Jones) to know that Frost had failed to find financial backing, was paying Nixon out of his own pocket and would be ruined if he didn’t get what he clearly needed. Then factor in Nixon’s envy of Frost’s popularity and genial personality. In one revealing moment, Nixon confides he would do anything to be able to attend a party and just relax around people. Nixon also questions him closely about his “girl friends.” Frost represented Nixon’s vulnerabilities, his shortcomings and even some of his desires.

This all sets the stage for the (fictionialized) scene that is the crucial moment in the story. A drunken Nixon calls Frost late at night. The next day, he doesn’t remember the call, but like an alcoholic after a blackout, he has an all too vivid imagination of what he might have said. At that day’s interview, he’s not only playing their chess game with a hangover, but has sacrificed his queen.

Frank Langella and Michael Sheen do not attempt to mimic their characters, but to embody them. There’s the usual settling-in period, common to all biopics about people we’re familiar with, when we’re comparing the real with the performance. Then that fades out and we become absorbed into the drama. Howard uses authentic locations (Nixon’s house at San Clemente, Frost’s original hotel suite), and there are period details, but the film really comes down to these two compelling intense performances, these two men with such deep needs entirely outside the subjects of the interviews. All we know about the real Frost and the real Nixon is almost beside the point. It all comes down to those two men in that room while the cameras are rolling.