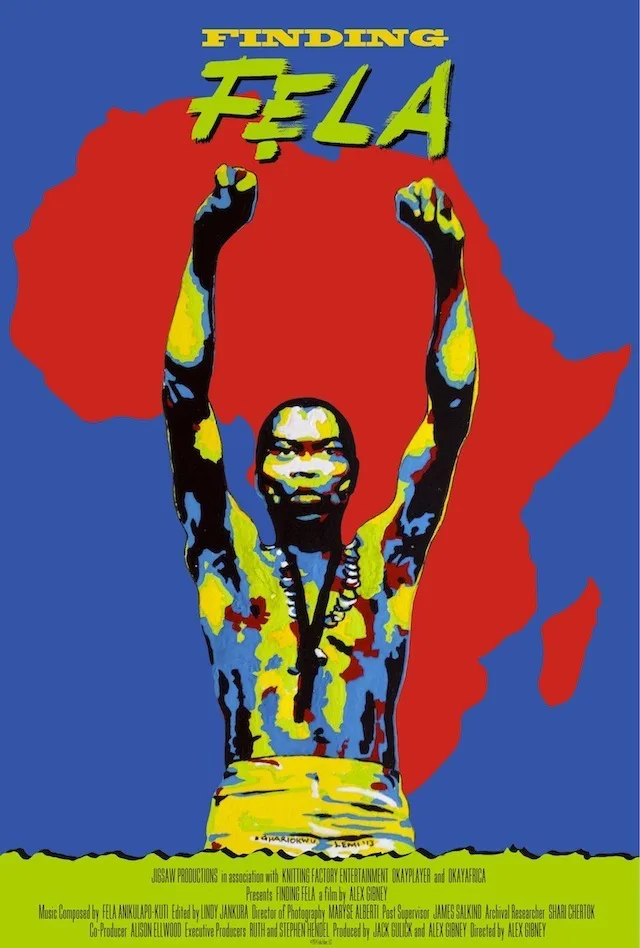

Documentarian Alex Gibney’s “Finding Fela,” about the legendary African pop star and political activist, feels like a rough draft for a very good movie.

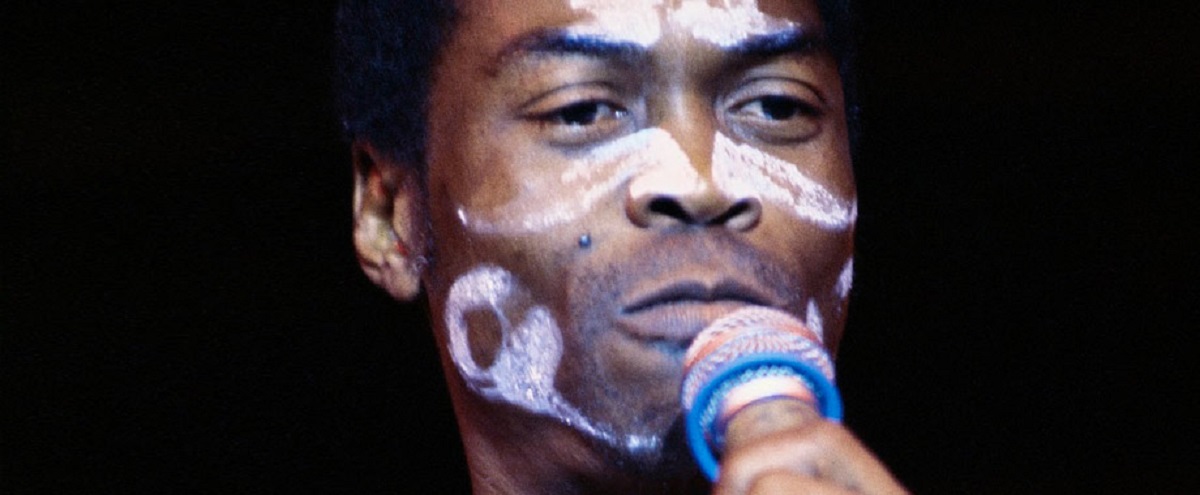

Parts of it are stirring because the subject matter is inherently noble. Fela Ransome Kuti, who died in 1997 at age 58, was multi-disciplinary songwriter, singer, bandleader and activist who invented Afrobeat music, hooked up with the Black Panther Party during a U.S. tour, then went home and mocked the dictatorial Nigerian government throughout the 1970s. He also formed a commune, Kalakuta Republic, that he declared a sovereign nation; started a nightclub called the Afro-Spot in the Empire Hotel in Lagos, and embraced the Yoruba faith, becoming a spiritual leader and even officiating at weddings.

Most of all, he was a great pop protester, working in a country where being that kind of performer required real sacrifice. Kuti was arrested or detained by police over 200 times during his career, and often the police actions were purely retaliatory harassment. Kuti’s music was compositionally bold but also danceable; commentator Questlove as being in the spirit of Bob Marley’s but requiring a “more sophisticated ear.”

But more than that, it was a vehicle for messages of pride and defiance against Nigeria’s repressive government, particularly its brutal police. Kuti teased them in songs such as “Zombie,” “The Mosquito Song” and “Go Slow” (about the horrendous traffic jams in the Nigerian capital of Lagos, which cops tried to speed up by beating any drivers who didn’t move quickly enough). The movie never attempts even a speculative answer to the question of why a notoriously thin-skinned and violent government allowed Kuti to mock them openly over so many years. And yet if you don’t know every detail of the story, this vagueness works in the movie’s favor; you worry that just around the next bend lurks the moment when the government finally gets fed up.

A life this packed with so much incident can’t help but be fascinating, especially when some of the incidents are personally harrowing. Kuti’s mother, the pioneering feminist and anti-colonialist activist Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, was thrown out of a window when police raided her son’s compound, then lapsed into a coma and died. Kuti also faced internal resentment and rebellion after his cousin emptied his bank account and his once-loyal bandmembers became increasingly disgruntled at having to play without being paid.

Was there enough existing film footage and still photography to fill out a feature-length documentary about Kuti without bringing in extensive backstage footage of “Fela!”, the Broadway music about him? Given the film’s two-hour running time, which wouldn’t be so onerous if the pacing weren’t so lumpy, I have to wonder. Gibney and his crew jump between a relatively straightforward documentary with talking heads and archival imagery and a backstage, “making-of” type documentary, about artists (including the show’s director-choreographer Bill T. Jones) analyzing Kuti’s motivations and mindset, the better to guide a show’s musicians and dancers.

The film barely settles into one groove before it’s unceremoniously torn out of it. Both documentaries are good (though the straightforward one, about the man himself, is rawer and more urgent than the backstage one, which too often feels like an extended ad for the still-touring musical); but you do often feel as though you’re watching different takes on the same subject glommed together. As a portrait of a great artist and activist, “Finding Fela” is worth a look, but it’s Gibney’s weakest work as a filmmaker.