This movie is sick. It pretends to be a warning against compulsive gambling, but it falls for the oldest dodge in the gambler’s book: “I only gambled enough to win back my losses.” Maybe I shouldn’t have expected anything more from an MGM movie that was shot on location at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. (To be fair, however, MGM is not scrupulous about its own image. In the movie, the MGM hotel manager happily sends a free hooker to the hero’s room.)

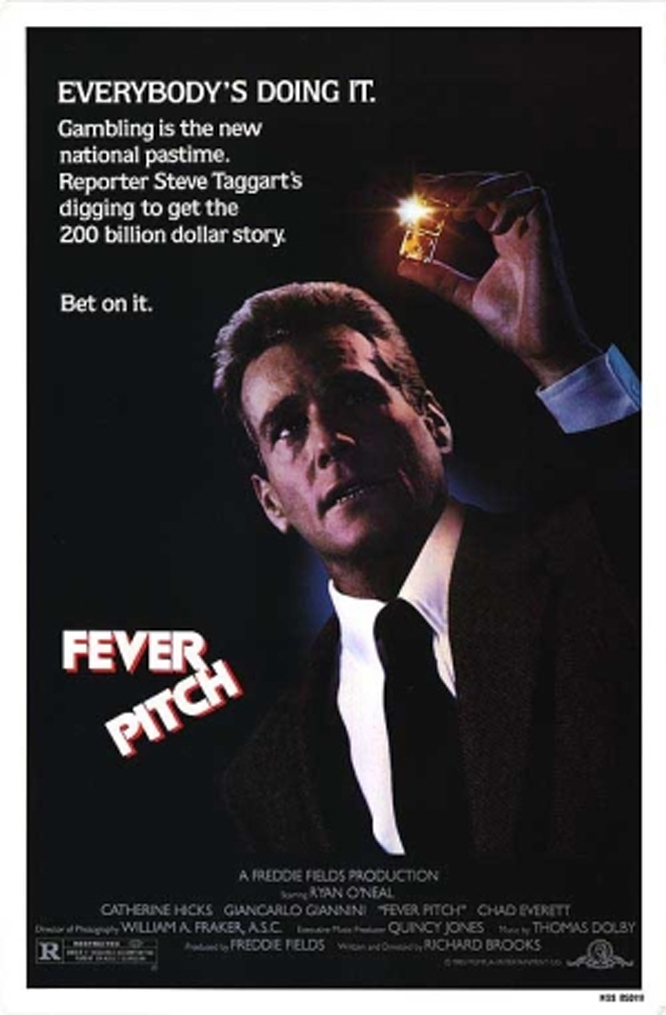

The movie stars Ryan O'Neal as a sportswriter who has been assigned to do a series on compulsive gambling. He is apparently on an expense account that would be adequate to do an expose on the Pentagon. He arrives in Vegas, checks into the Grand, and starts to interview the winners and losers. The only catch is O’Neal is a compulsive gambler himself, and he owes a gangster lots of money because of bets he’s lost on big games.

The movie is written and directed in an odd, dated style; it’s like a throwback to hard-boiled 1940s gangster films, but it has some touches of its own, like dialogue that sounds borrowed from pulp novels, and characters who disconcertingly start talking in rhymed couplets. The filmmaker is Richard Brooks, a veteran of many great movies of the 1940s and later, but this time he hasn’t found a style that suits his material. O’Neal looks and sounds so odd in this garish, neon-lit melodrama that he is hardly ever convincing.

The movie’s hyperkinetic editing style doesn’t help. Neither does a tortured flashback, in which O’Neal’s wife is trapped in a car crash while racing to bring him money so his poker cronies won’t break his legs. The crash takes her off the scene, and there’s a love interest between O’Neal and Catherine Hicks, as the casino waitress who doubles as the house hooker.

The opening segments of the movie are simply odd, distracting and unconvincing. It’s the movie’s final act that is sick. O’Neal finally grows convinced that he has a problem. He realizes he is a degenerate gambler and needs help. So he goes to a Gamblers Anonymous meeting, and finds the courage to stand up and identify himself as a compulsive gambler. He walks out with the leader of the meeting, who explains G.A. to him in a scene that sounds dictated by the film’s technical advisers.

Fine. He has a problem and he’s found a way to try and deal with it. But can you seriously believe that MGM, with its giant investment in gambling, would allow the movie to end with O’Neal cleaning up his act and returning happily to life outside the casinos? No way. After he leaves the Gamblers Anonymous meeting, O’Neal goes to the airport, where he tries his luck on a slot machine. He wins. This is obviously a sign that his luck has changed, right? So he takes his new nest-egg back to the casino, where during an incredible winning streak he parlays his new stake into the $89,000 he needs to pay off the mob and set up a trust fund for his daughter.

Once he’s won the $89,000, does he continue to gamble? He’s tempted. He holds the dice up in the air, and they glow like radioactive ingots. But then he hurls them across the room and leaves, determined never to gamble again. In other words, after he faced his addiction at the Gamblers Anonymous meeting, he improved to the degree that he only needed to gamble long enough to win back the $89,000 he needed. In real life, of course, he probably would have lost again, and gotten his kneecaps smashed.

If this movie had been a remake of “The Lost Weekend,” I guess it would have ended with Ray Milland leaving the A.A. meeting and getting drunk — but only just enough to get a nice buzz, of course.