Near the end of the insistently weepy “Fathers and Daughters,” Aunt Elizabeth (Diane Kruger, aged up with makeup) tells her niece Katie (Amanda Seyfried), with a weariness that can only be cultivated by a life of disappointment, that “men, they can survive without love—but not us women.”

Deeply questionable anthropological assertions aside, the scene’s framing and timing suggests we’re meant to take this as at least one of the film’s theses. Which is weird, because it’s definitely not the story the film tells as it shifts back and forth (largely seamlessly) between two timelines.

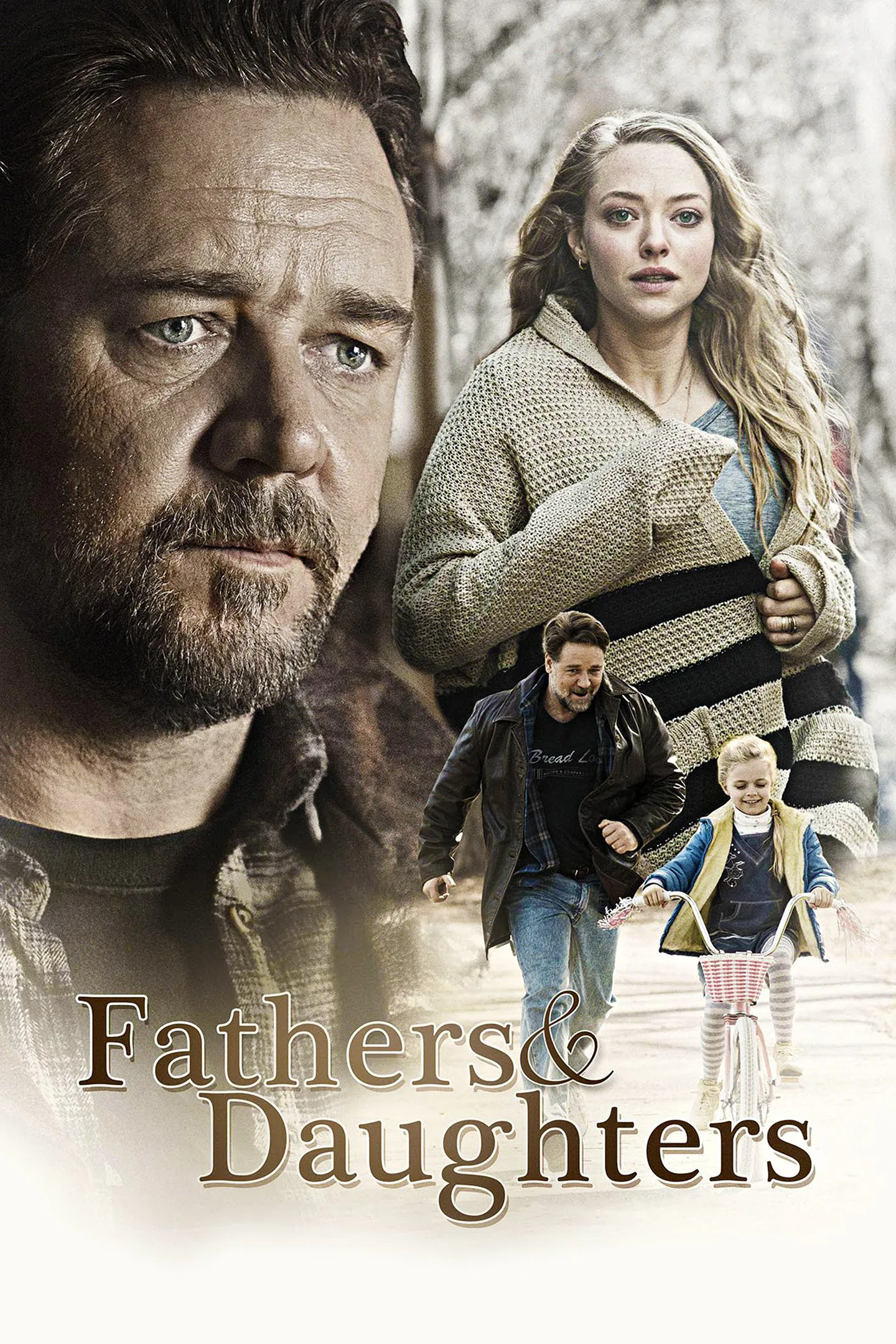

In the first, Jake Davis (Russell Crowe), a Pulitzer-winning novelist, loses his wife in a car accident. He was driving, and they were having an argument related to his years-ago infidelity, and their young daughter Katie (skillfully played by Kylie Rogers) was in the back seat. After the accident, trauma-related injuries coupled with a depressive disorder send Jake to an institution, and Katie goes to live with her Aunt Elizabeth—her mother’s sister—and Uncle William (Bruce Greenwood) for seven months. Jake returns and is informed by Elizabeth and William that they’d prefer to adopt Katie, doubting he can provide for her sufficiently. As you might suspect, they have some other motivations, too.

That kicks off the rest of the action, and the film cuts between this history and thirtyish Katie, now a Ph.D. student studying psychology and working with a young girl, Lucy (Quvenzhané Wallis), who hasn’t spoken since her mother’s death. Katie also self-medicates by hooking up with men in bathrooms and at bars and drinking, a behavior she tells her therapist helps her “feel something.” (She’s a budding psychologist and she has emotional attachment problems, and that’s ironic, get it?) Then Katie meets Cameron (Aaron Paul), who idolizes her father and, as it turns out, is a loving and longsuffering boyfriend. Katie is scared of commitment and tries to drive him away. Will love win out?

Despite its title, “Fathers and Daughters” is only interested in one father and one daughter, and in one idea: that your childhood experiences help shape your relationships and actions in adulthood. That’s not a particularly provocative idea—when John Mayer has written a song about it, you know it’s over—but then, there’s regrettably nothing very provocative about “Fathers and Daughters.” Each plot point plods along with utter predictability. You know as soon as Jake enters an institution that he’ll have trouble keeping Katie when he gets out, just like you know as soon as you see Katie hooking up with a guy at school that the film will characterize her actions as an effort to exorcise some demon. (The only surprising thing about the movie is that William and Elizabeth aren’t childless.) With each big scene, the film signals hard via swelling music and self-consciously meaningful one-liners that you’re meant to feel here.

The thing is, sometimes you do. Melodrama can have its merits when the players are good, and “Fathers and Daughters” is top-heavy with acting talent. The father-daughter chemistry between Crowe and Rogers feels natural whether they’re hugging or fighting, and Seyfried’s expressive performance transforms a role that seems borrowed from a Lifetime potboiler into something much more empathetic. Brad Desch’s screenplay for “Fathers and Daughters” made the Black List in 2012, and director Gabriele Muccino (“Seven Pounds,” “The Pursuit of Happyness”) has ample experience with this sort of material. It’s lavishly shot and styled. It’s nice to look at.

Which leads us back to Aunt Elizabeth’s suggestion that men don’t need love to live, but women do. “Fathers and Daughters” strongly suggests the latter is true—Katie’s promiscuity is slowly killing her—but that the former isn’t at all. Both Jake and Cameron refuse to live without love. You could argue that Elizabeth is wrong, but the statement just hangs there in the air, left unrefuted and uncontested, as if it speaks for itself.

It’s the lines like these—statements that sounds profound, but mean next to nothing—that really sink “Fathers and Daughters.” If it didn’t so obviously want to be a Serious Adult Drama, leaned into its own melodrama with zest, it could have been pretty good. As it is, it feels like a misfire that’s trying just a little too hard to be Oscar bait. But in some ways that’s what makes it watchable: put great actors in a middling film, and you’ve still got some fine performances to watch. Pair “Fathers and Daughters” with a bottle of wine and a friend on a rainy night, and it will work just fine.