During the dark war days of 1942, the U.S. government gathered a group of the most brilliant scientists in the nation and sent them to live in the dust and mud of Los Alamos, N.M., where the Army had hammered together a town for them overnight. Their mission on this top-secret base was to design and build an atomic bomb. They made an odd assembly, the intellectuals from Berkeley and Chicago, the refugees from Hitler, the tinkerers and craftsmen who were to physically construct the bomb, and all of their wives, children, lovers, pets, libraries, pianos and eccentricities. To weld them together, the Army assigned Gen. Leslie R. Groves, whose previous task had been to build the Pentagon.

Their endeavor was known as the Manhattan Project, and they were told they were in a race with Germany to build the first doomsday weapon. Germany surrendered before the bomb was finished, but it was used, of course, on Japan, and the shadow cast by its mushroom cloud still hovers over all of us today. “Fat Man and Little Boy” is a fiction based on the Manhattan Project, but it is thin and unfocused and hardly even suggests the enormous moral and practical questions that the scientists wrestled with in the New Mexico desert.

The movie labors under an enormous handicap: A much better, more intelligent and more exciting film has already been made about this same subject. It is “The Day After Trinity” (1980), a documentary by Jon Else that includes government footage from Los Alamos as well as interviews, then and now, with many of the men who worked on the bomb.

In my review of “The Day After Trinity,” I wrote that it “delivers more suspense than most of the thrillers I have seen,” and now that we have a fiction film to compare it to, that is even more clear.

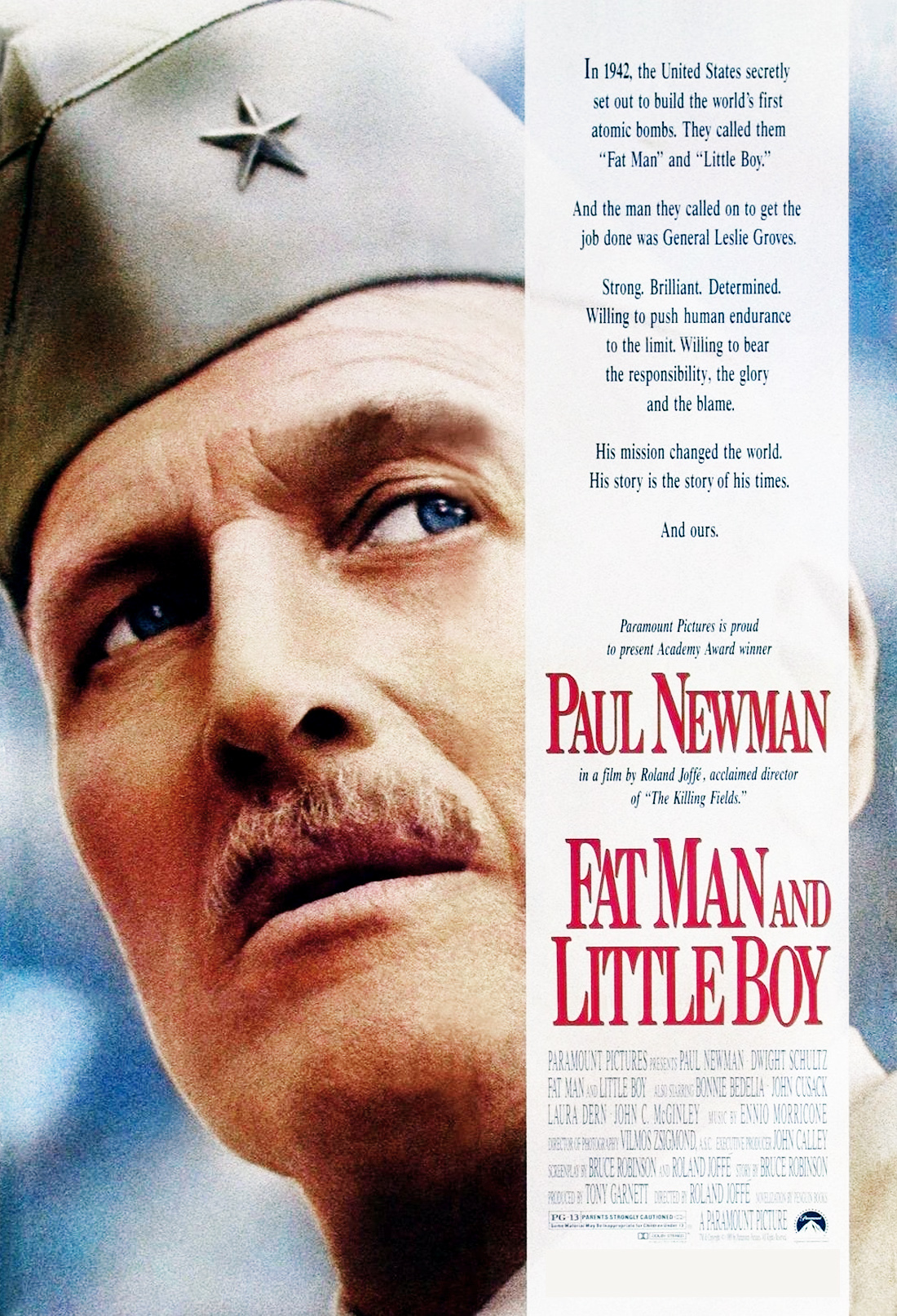

The story of the birth of the bomb is one of high drama, but it was largely intellectual drama, as the scientists asked themselves, in conversations and nightmares, what terror they were unleashing on the Earth. “Fat Man and Little Boy” reduces their debates to the childish level of Hollywood stereotyping, giving us a simplified personality conflict between Gen. Groves (Paul Newman) and J. Robert Oppenheimer (Dwight Schultz), the scientific leader of the undertaking.

Gen. Groves is portrayed as a saner, gentler version of George Patton – gruff, barking orders – and Oppenheimer is seen as a brilliant but unworldly intellectual. Since the two men do not really violently disagree on anything, their conflict reduces itself to emotional speechmaking, which, when carefully listened to, is not really about anything.

“The Day After Trinity” paints a picture of the community that grew up in Los Alamos, where the music of Glenn Miller and the popularity of the martini helped to break the tension after the day’s work. “Fat Man and Little Boy” simplifies this, too, by showing the social life but not the tension. Most of the scientific details in the movie are reduced to scenes like the one where a young scientist (John Cusack) triggers an experiment, holds his breath, and then relaxes when the world does not vaporize. After work, the scientists attend cocktail parties that seem to exist only to introduce minor characters, or they sit around holding earnest (but very brief) discussions that are so simplified by the screenplay that they sound like parodies.

The usual romantic subplots don’t contribute much. Oppenheimer is torn between his left-wing, security-risk mistress (Natasha Richardson) and his adoring wife (Bonnie Bedelia), who essentially thinks he is the greatest man alive and deserves anything he wants. The Cusack character also has an adoring woman, a local nurse (Laura Dern) who whispers that she loves him as he dies of radiation poisoning. But the movie is cobbled together so ineptly that Cusack’s death scene is intercut with the night of the first bomb test and is so thoroughly upstaged that it never really gets the emotional reaction it deserves.

This movie, written by Bruce Robinson and the director, Roland Joffe, can’t even steal successfully. In “The Day After Trinity,” there is gallows humor as a scientist remembers that he and his colleagues placed bets before the first atomic explosion on whether it would destroy the world, or only New Mexico. They thought there was a real possibility the first nuclear explosion would rip the fabric of matter and expand wildly out of control. If “Big Man and Little Boy” had simply recycled the dialogue and the incredibly exciting events of that day, it would have had an ending. Instead, Joffe is unable to deliver a climax even as the bomb explodes; he shows it reflected in the goggles of a character, and then cuts to what looks like special effects footage of nuclear flames.

Much of the imagery in “Fat Man” is obviously inspired by the earlier documentary footage, including such details as what the first bomb looked like and how odd it was suspended in a tower in the desert.

The look of the film is nevertheless all wrong. Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography bathes everything in muted browns and golds and maroons, so that New Mexico looks like outtakes from “The Godfather” when it should look stark and bright in the Southwest sunlight, and painted with bold O’Keefe colors.

As for the performances, they are mostly hapless. Newman is unable to generate any particular tone for his Gen. Groves – no wonder, since the character has been written as a schoolmaster and scold – and Schultz’s Oppenheimer lacks the quickness and fire of the real man, and seems curiously muted and befuddled. Many of the scientists at Los Alamos were young, it is true, but were they as young as the actors who play them here? Wearing their fedora hats and rimless glasses and smoking cigarettes, some of these actors look like high school kids playing adults in the class play.