Albert Camus’ short story, “The Guest,” rather resembles Ernest Hemingway’s “The Killers” in that it uses an almost anecdotal storyline to illuminate major—hell, one might even say “existential”—themes. Camus’ work has only three characters: a police officer, his prisoner, and a schoolteacher the police officer charges with taking said prisoner to a court and jail a couple of hours away. The teacher’s refusal sets the tale in motion, demonstrating how choice is destiny, but sometimes choice is not an option. Hemingway’s somehow even sparser story focuses on its two title characters, and a man called The Swede, their victim, who offers his murderers no resistance; recounted second hand, the tellers of the tale ponder The Swede’s stoic acceptance of his fate.

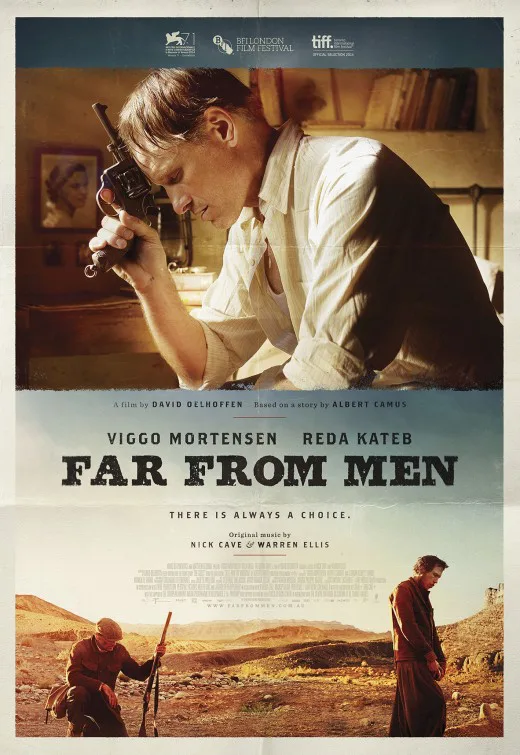

“The Killers” was made into a movie in the late ‘40s, one that extrapolated The Swede’s backstory in full. A pretty great film noir directed by Robert Siodmak and starring Burt Lancaster and Ava Gardner. But an almost entirely different animal in spirit than Hemingway’s great story. Similarly, writer/director David Oelhoffen expands the parameters of Camus’ story, set in Algeria in the early ‘50s, in “Far From Men”.

Schoolteacher Daru, a quiet, self-possessed man, is played by Viggo Mortensen; his charge, Mohamed, by Reda Kateb. This expansion of the story sees Daru escorting Mohamed even as he encourages the prisoner to break away. As the two men grow to trust each other, the impossibility of Mohamed’s situation is illuminated. Yes, he is guilty of a crime. The crime, he says, was the result of a him-or-me-and-my-family decision. Left to hang by themselves, though, his actions will create an endless and destructive cycle of recrimination. If he escapes, he insists, nothing will be solved. Only his own sacrifice will make things right. “Getting killed by the French is the only solution.”

Daru has a hard time grasping this. Their journey offers other challenges as it progresses. There is rain. The Algerian rebellion against French rule had begun. It hasn’t had much impact on the mountain village where Daru teaches, but Daru and Mohamed meet some soldiers on their trip, which provides an opportunity for some backstory. It also recalls, in a low-key way, an episode from Leone’s “The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly.” There is a very understated brothel, recollecting “The Last Detail.” There is a lot of stark natural beauty, captured very well by cinematographer Guillame Deffontaines. And there is…not a lot more, as it happens.

In addition to muffing the dénouement of the story on which it’s based, “Far From Men” is also the kind of movie in which sobriety and a stalwart sense of seriousness yield more inertia than profundity. Its solemnity never becomes actively oppressive, but it shuts out not just humor but grace. What it falls back on, rather than the troubling truth illuminated in Camus’ story, is the movie-standard gaze of compassion, here proffered by Mortensen, who, it must be admitted, does it well. His French isn’t bad either, although his character gets a backstory that explains its sometimes halting quality (French natives are worse sticklers for accents than American movie critics, as it happens). His work, and Kateb’s, are exemplary. It’s also pleasant to see the great Angela Molina, so memorable in Luis Buñuel’s final film “That Obscure Object of Desire,” pop up here in a small role. But the movie remains something of a Distinguished Slog.