Writer Robin Beth Schaer’s tweet about a soap dispenser went viral in 2019: “My friend & her husband lived in an apartment that had a soap dispenser installed on the edge of the kitchen sink. When they moved out after two years, he marveled to her: ‘It’s amazing how that dispenser never ran out of soap in all this time.’ Women’s work is truly invisible. She never told him the truth. He still thinks wistfully of that amazing, magical soap dispenser they had once.”

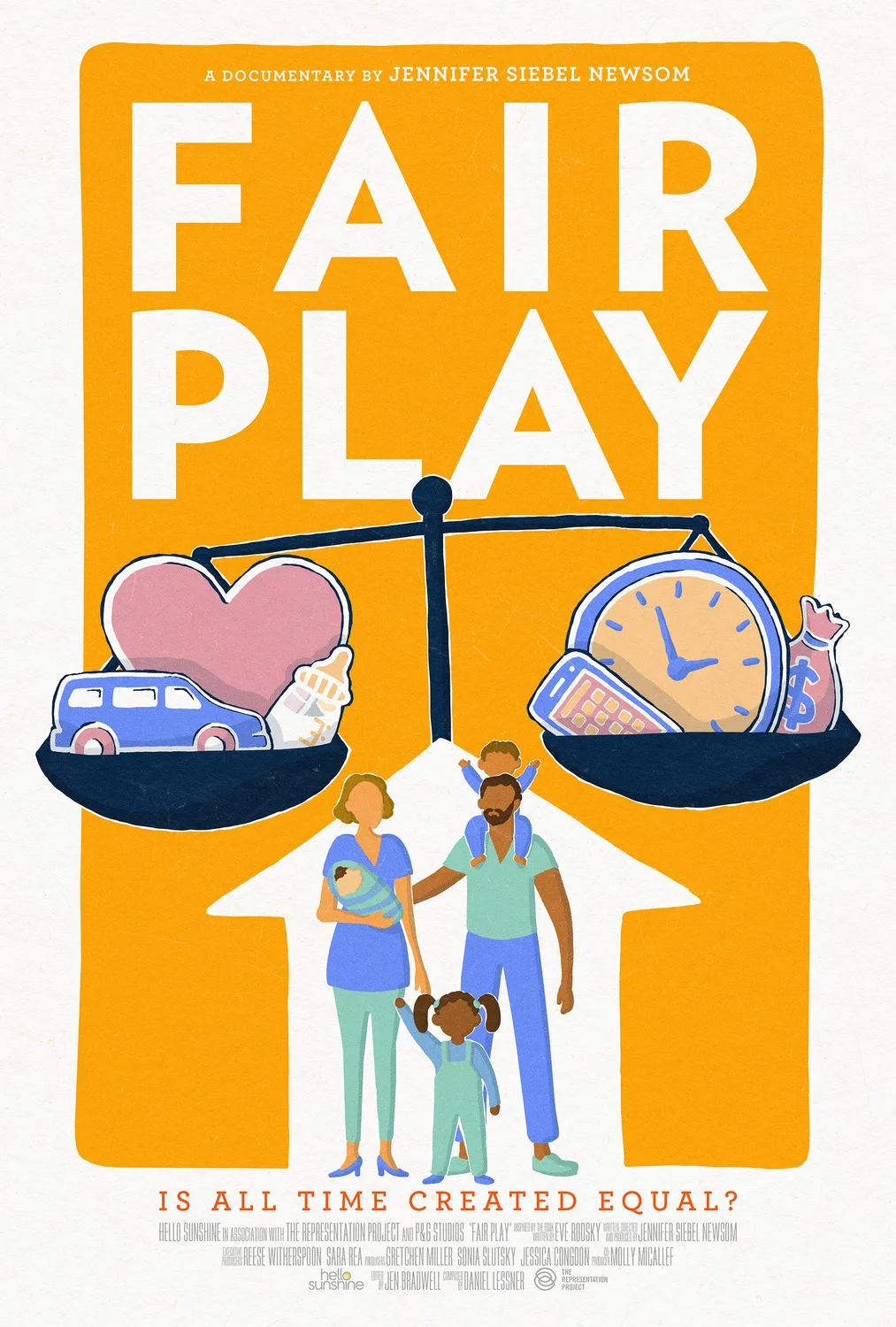

The tweet inspired many responses from women about what has been called “the second shift,” “emotional labor,” or “the mental load.” It is the feeling of frustration many women feel when they constantly carry the anxiety-ridden checklist mindset about children and housekeeping. “Fair Play” is a documentary based on the best-selling book written by Eve Rodsky, a Harvard-educated lawyer, about the disparity in domestic responsibilities. She describes herself as “working to change society one partnership at a time by coming up with a new 21st-century solution to an age-old problem: women shouldering 2/3 or more of the unpaid domestic work and childcare for their homes and families.”

Every couple Rodsky asks at the beginning of the film about the division of labor disagrees about how much the husbands do. One couple both insisted they did 70 percent of the child care. The wives are all good-humored but occasionally there’s an edge to their comments. “Eating the food doesn’t count,” one notes.

Here’s a hint: if someone describes what he does as “help,” it shows that he thinks it’s a generous voluntary impulse, not an essential continuing responsibility. Those who believe their contribution is picking up milk at the store when asked need to realize that the more exhausting part of the job is constantly being aware of when milk is needed, not to mention bread, cereal, cheese, fruit, peanut butter, signed permission slips, dry cleaning, allergy shots, and piano lessons. One husband defends himself by describing his office’s “traditional” culture, which meant that when his wife had a baby on a Friday night, he was back in the office Monday morning. He later notes that a part of that office culture is that most of the men are divorced.

The problem became clear to Rodsky when she and nine other women were supposed to have lunch together after a breast cancer march. All were in dual-career relationships and their husbands were home with the children. In 30 minutes, the women received 30 calls and 46 texts, asking questions like “Where is the gift for the birthday party?” and “Do the kids need to eat lunch?” The women all left for home so they could take care of things, some apologizing for giving their husbands more than they could handle.

Rodsky applies her systems analysis skills to document the differences with a massive spreadsheet. The film has some statistics to back up her assessments, along with commentary from various experts, including Melinda Gates. We also meet some people struggling to create more balance, including Rodsky, her husband, and two couples she is advising. California Congresswoman Katie Porter speaks about her experiences as a single mother to underscore the systemic “family-hostility” of US laws on parental leave, child care, and minimum wage. She pointedly calls out her colleagues, the older white male lawmakers, for assuming their own experiences are the norm. Same-sex couples, with less burden of gender expectations, genially provide a road map for negotiating domestic responsibilities.

There is some diversity of race but not much of class or economic level in the film. The only family that is not financially comfortable are immigrant farmworkers. When that husband cuts back on his hours to spend more time with the family, there is no indication of the impact on the family of the reduction in income. There is little discussion of how families who can afford help remove some of the endless pressure of housework, other than comments from Ai-jen Poo, president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, on how these workers are chronically underpaid.

It is not clear who this movie wants to speak to. Women do not need to be persuaded that too often there is a discrepancy in the emotional burden of caring for home and children. If it is men who need to be persuaded, the discussion of the improvement in men’s physical and mental health (and more sex!) when they form a truer partnership at home should probably have been at the beginning. If the intention is a “An Inconvenient Truth”-style contribution to public policy discussions, the optimism about finding a more equal ownership of issues (like when we need milk) through couples communicating better ten minutes a day is unlikely to make that case. For one, it overlooks the common response that the partner who cedes some of the authority often finds it surprisingly hard to stop giving orders.

The film’s good intentions are evident, but its assemblage of experts and statistics is more lecture than movie. There is too much focus on families of comfortable or better means and too little focus on the impact that these conflicts have on the other members of the family. Children need good examples of respectful partnership, cooperation, and compromise. We all say we want our children to be happy. The best way to do that is to give them an example of parents who know how to be happy.

Now playing on AppleTV+.