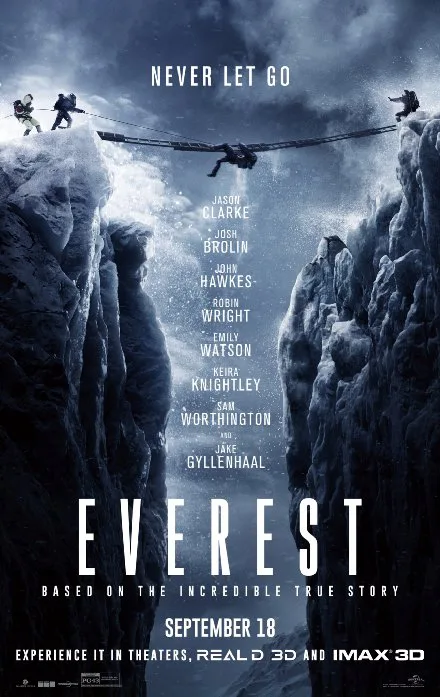

“Never Let Go” is the tagline on posters for this movie, based on the true story of an exceedingly ill-fated trek up the title mountain in 1996. “What The Hell Are You All Doing Up There In The First Place?” might be a more apropos. The transformation of massively risky mountain-climbing, as an activity exclusively for scientists and highly-trained explorers to an adventure-tourism endurance test for the rich and obsessive, gets taken care of here in a series of three title texts at the beginning of the movie, starting with the ostensible conquest of Mount Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary’s team. Beginning with some tantalizing/troubling glimpses of the heedless and colonialist aspects of adventure tourism culture, “Everest” then gets down to business. This movie, scripted by William Nicholson and Simon Beaufoy and directed, with meticulous regard for the elements and action, by Iceland-born filmmaker Baltasar Kormákur, is a detailed and realistic depiction of climbers—of various experiences—facing the worst possible conditions, at heights and climates that seem designed to shut a human body down.

Jason Clarke’s Rob Hall is an experienced climber and the head of a company called Adventure Consulting. He’s a good-hearted bloke who’s got a devoted team and a relatively diverse clientele. The climbers putting out big bucks (or, in some cases, as it happens not; Hall, we learn at one point, is even more good-hearted than he appears) for a spring jaunt up Everest include cocky Texas businessman Beck Weathers (Josh Brolin), good-natured workingman Doug Hansen, and very game Yasuko Namba (Naoko Mori) a petite powerhouse who’s topped six of the so-called Seven Summits and now wants Nepal’s Everest, the highest of the bunch. The conditions at base camp are hectic and slightly tense. A star journalist, Jon Krakauer, is part of Hall’s expedition, which has aroused the envy of a Hall’s pal Scott who’s now a rival climb organizer (played Jake Gyllenhaal, portraying the more hippie-ish side of the climbing gestalt). There are scheduling issues and various manifestations of pissiness between the teams that go up the mountains and prep climbing tools for their clients. Clearly, there’s a lot that can go wrong. Particularly if the weather turns bad.

There’s a resemblance here to both the story and the movie adaptation of the story told in “The Perfect Storm.” The characters involved are making a good faith effort—but good faith efforts by humans can only go so far. “Nature always has the last word,” one character observes early on. As the movie expertly depicts freezing conditions, approaching and full-blown storms, mini-avalanches hitting at just the wrong place and just the wrong time, and more, the movie provides an object lesson with respect to that adage.

As much as “Everest” trades in a kind of authenticity, it also trucks in the most banal of disaster movie clichés; for instance, one of the principal characters in the trek is leaving behind a pregnant wife. While this part of the story is as true as any other, the dialogue between the characters at the outset: “You better be back for the birth, [Full Character Name];” “You try and stop me,” practically screeches to the audience, “Start worrying about this guy NOW.”

What it all amounts to, finally, is an excruciating and dispiriting simulated recreation of excruciating and dispiriting real life events. While leaving the theater, I overheard several sets of people discussing the various actions some of the characters took and what they, the viewers, might have done in their stead. This occasioned some slight despair on my part. “You can’t stop what’s coming,” as someone once said in another movie starring Josh Brolin, and I rather doubt that the filmmakers’ aim in making this picture was to excite the vanity of its audience. The point, as far as I understand it, isn’t “You could live if you did things differently than X” but rather that even the best-prepared are not really prepared.

Not that I’ve ever been a “What’s the point?” kind of person in my aesthetic enthusiasms. But in spite of the excellent technical work and the efforts of a first-rate cast, “Everest” did not exhilarate or scare me as much as leave me flatly sad. A real-life footage coda to the movie suggests that the participants signed off on this portrayal, and in a sense it’s an apt and sensitive tribute. A good many accounts of the 1996 events have been told in book and movie form—Krakauer’s own highly-regarded book “Into Thin Air,” Beck Weathers’ memoir, and more. I myself worked on a piece for Premiere magazine focusing on the event from the perspective of David Breashears, who made the IMAX film “Everest” (1998) and who appears as a minor character here. I’ve not read Krakauer’s book, but perhaps I should. Coming out of this movie, the story remained upsettingly senseless to me, and an inapt one for a movie that. Despite its attempts at empathy, “Everest” often plays the cinematic thrill ride card.