Evel Knievel is the man who wants to leap across the Grand Canyon on a jet-powered motorcycle, a project that’s been delayed for a couple of years by the problem of getting an insurance policy. Or, as Variety reported in its inimitable prose: “Not yet decided is who collects should flight not prove horizontal.”

The problem with making a movie about Evel Knievel must have been similar. How do you end it without showing the Grand Canyon jump, especially since the real Evel is still alive? And, if you don’t show the jump, how do you end the movie at all — since the big jump seems to be Evel’s personal choice of locale when death, as it must to all men, comes to him.

I’ve given this question a lot of thought, ever since that Esquire article on Knievel appeared. Daredevils fascinate me, especially those who dare hopeless causes, and I’m still haunted by the fate of a man named “Red” (can’t remember his last name) who tried to go over Niagara Falls in a capsule made of tractor-tire inner-tubes and held together with nylon net. All they ever found was one of the inner tubes. Seems to me Red made his big try in about 1950, and he made it into a lot of my nightmares for a couple of years afterward.

My notion of an ending for “Evel Knievel” is a little odd, but see how you like it. We start with a long, slow sunrise shot of a giant quarter-mile takeoff ramp on one bank of the Grand Canyon. Thousands of observers have already gathered round, spreading their blankets and peeking into their beer coolers. On the other side of the canyon, there’s another huge ramp, with tons of sawdust all around it, where Evel’s going to land.

These shots should, of course, be shot in 70 mm. Panavision, like the opening panoramas of “2001,” and they should suggest the immense prehistoric calm of the arena. Even the thousands of fans, driving their Chevies and camper-trucks into monumental traffic jams, are tiny dots on the face of nature. Then we come in for close-ups of the fans, and we realize that Evel Knievel’s final jump is the occasion for Middle America’s first Woodstock. It is only fitting.

Then (after the obligatory shots of Evel talking with his wife, his taxman and his doctor), we get the jump itself. Evel takes off in a mighty roar of flame and dust and noise, all wrapped in his American flag leathers, and disappears from the end of the ramp and into the high blue sky. Then we cut to the other side of the canyon, and all the fans waiting over there, and we aim the camera at the landing ramp. Nothing happens for three minutes, and then the cast credits appear on the screen.

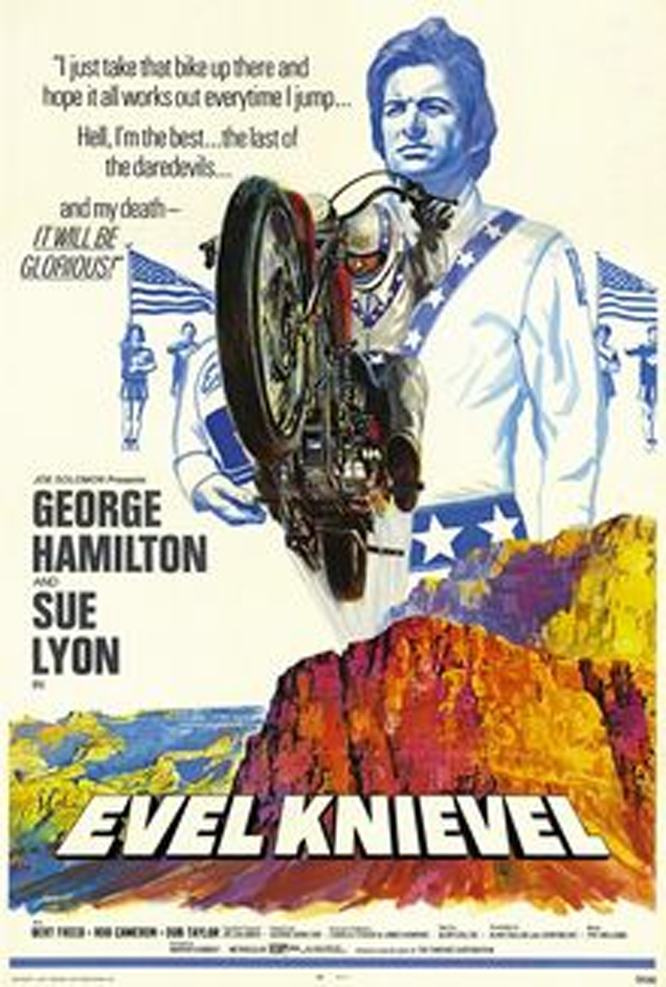

This is maybe a little gloomy way to end it but, to me, the life of Evel Knievel contains the same seeds of self-doom as a Dostoevski character’s. That’s what I miss in the current George Hamilton movie version, despite its generally interesting texture and its flicks of black humor. Evel Knievel is a man who, for unknown and probably terrifying personal reasons, has set out to methodically punish himself in a spectacular public way.

I was talking about this characteristic of Evel’s once with Joe Solomon, whose Fanfare Films produced “Evel Knievel,” and Joe said he thought maybe Evel’s mother had something to do with it. When Evel tried to jump the fountain at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas and broke about a dozen bones, Solomon said, Evel’s mother was inside the hotel — and didn’t even come out to look!

Well, what can you say? What can a movie say, for that matter, about such a uniquely driven man? George Hamilton and director Marvin Chomsky have tried a slice-of-life approach, with shots of the young Evel trying to outrun police cars, charging up the stairs of his girl’s dorm on a cycle, making his first stunt jumps with a rodeo, etc. They also do a couple of other interesting things. They make Evel a hypochondriac. He’s afraid of being X-rayed, terrified of polluted water, convinced that his fans will tear him apart (“A 14-year-old girl almost killed Elvis once”) and afraid, indeed, of almost everything in his life except his jumps.

This seems to fit, somehow. The movie Evel says he keeps high on terror: “Not fear — terror!” We get a notion of what he means when we see newsreel footage of the real Knievel taking that horrible spill at Caesar’s Palace and rolling over and over, tangled in his bike, for dozens of yards.