Now that two movies have been made about a man living 24 hours a day on television, how long until TV actually tries this as a programming idea? “EDtv” arrives less than a year after “The Truman Show,” and although the two films have different approaches (“Truman” is a parable, “EDtv” is an ambitious sitcom), they’re both convinced that enormous audiences would watch intently as a man brushes his teeth, clips his nails and is deceived by a wicked woman.

Is this true? Would they? Much would depend on the nature of the experiment, of course. “The Truman Show” gathered its poignancy from the fact that its hero didn’t know he was on TV. “EDtv” is about a man who auditions for the job; as his brother points out, “How many chances do guys like us get?” The two movies offer us a choice: Would you rather be a hidden voyeur, or watch an exhibitionist? I’d rather be a voyeur. The star of a TV show like this is likely to show me more about human nature if he doesn’t know I’m watching. The kind of guy who would agree to having his whole life televised, however, is essentially just a long-form “Jerry Springer” guest. Anyone who would agree to such a deal is a loser, painfully needy or nuts. And since the hero of Ron Howard’s “EDtv” isn’t really any of those things, the film never quite feels convincing.

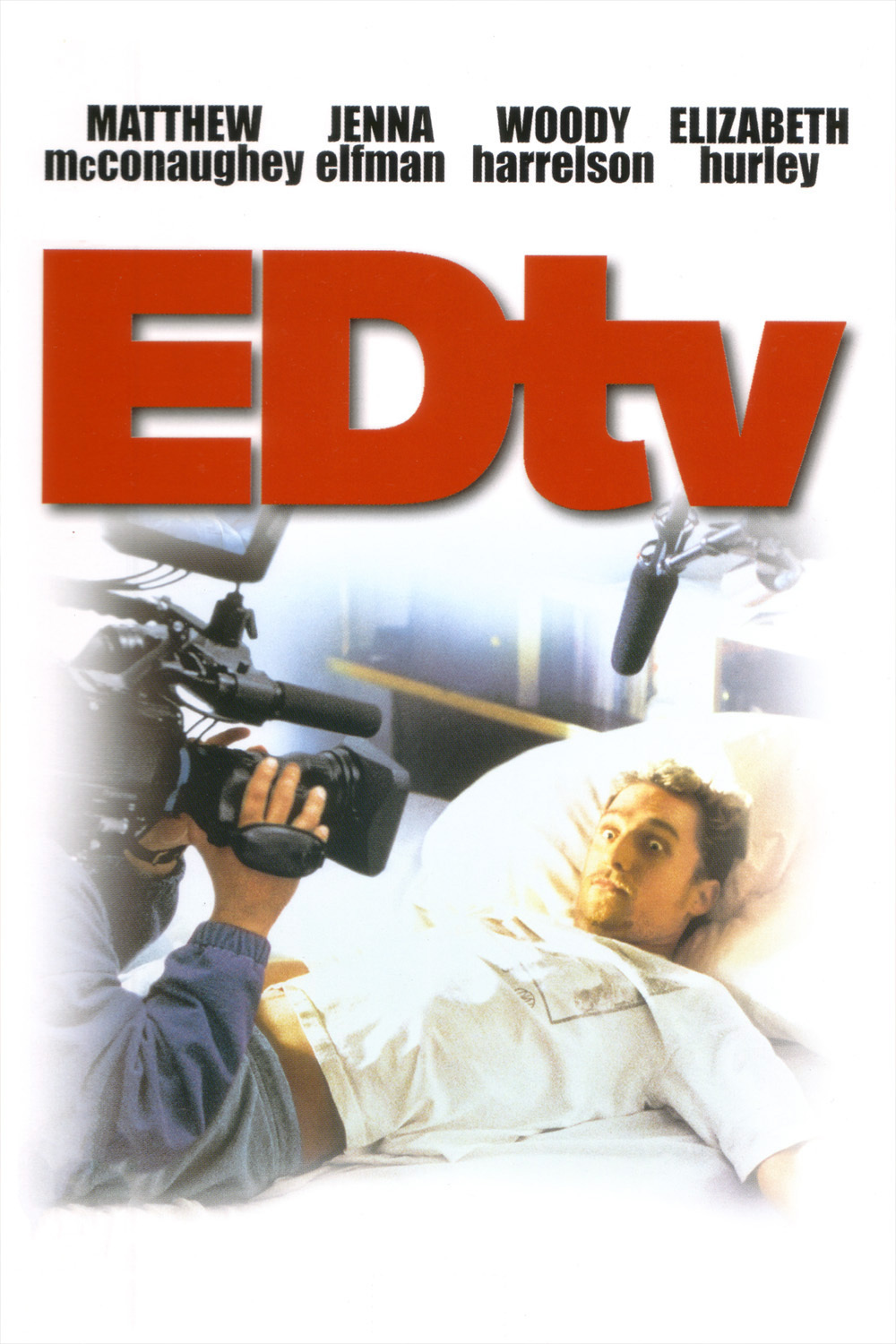

The film stars Matthew McConaughey as Ed Pekurny, a Texas charmer who is discovered during auditions by a desperate cable channel. He can talk “regular” or he can talk Texan, he says, demonstrating accents as a TV producer (Ellen DeGeneres) watches, enraptured. Televising Ed’s life is her idea; her boss (Rob Reiner) has his doubts at first, until she points out their current ratings are lower than the Gardening Channel (“People would rather watch soil”).

Ed is signed by the channel, which also gets releases from the people in his world, including his brother Ray (Woody Harrelson), Ray’s girlfriend Shari (Jenna Elfman), his mother (Sally Kirkland) and his stepfather (Martin Landau). The first hours of the new show are slow-going (including the toenail-clipping demonstration) but things pick up after it’s revealed that Ed and Shari are poised to start cheating on Ray (“I just kissed my boyfriend’s brother on television!”).

The movie strikes an uneasy bargain between being about television and just being a straightforward romantic comedy. After a few set-up scenes, we never have the notion that Ed’s whole life is being shown on TV; the alleged cinema-verite approach has an uncanny way of always being there for the right moments, with the right camera angles. And when they’re needed for story conflict, new characters arrive; Ed’s birth father (Dennis Hopper) appears for some touching confessions, and when a USA Today poll shows that viewers are bored with Shari, the producers arrange for a British sex bomb (Elizabeth Hurley) to appear on Ed’s viewfinder.

The juiciest character is Ray, played by Harrelson as a man always on the edge of someone else’s success. After it’s announced on TV that he’s a lousy lover, he actually produces a defense witness–a former girlfriend who testifies, “I’ve had worse.” The character I never quite understood was Shari, who becomes totally disillusioned with the idea of having her romance telecast, even though she’s so oblivious to the cameras that she dumps Ray and embraces Ed in full view of millions during the first few days.

The movie has a lot of TV lore, including programming meetings presided over by Reiner, whose enthusiasm for “EDtv” grows as DeGeneres loses hers. The story arc is obvious: TV is bad for invading the privacy of these lives, and we’re bad for watching. Still, Ray was right: The brothers had nothing going for them before, and now Ed is rich and famous. If he doesn’t have the girl he loves, at least he has Elizabeth Hurley as a consolation prize. The story keeps undercutting its own conviction that TV is evil.

I enjoyed a lot of the movie in a relaxed sort of fashion; it’s not essential or original in the way “The Truman Show” was, and it hasn’t done any really hard thinking about the ways we interact with TV. It’s a businesslike job, made to seem special at times because of the skill of the actors–especially Martin Landau, who gets a laugh with almost every line as a man who is wryly reconciled to very shaky health (“I’d yell for her, but I’d die”). After it’s over, we’ve laughed some, smiled a little and cared not really very much.