Footprints in the sand lay inches away from the progressing waterline of the shore, which eventually creeps far enough to wash them from existence. These are the opening moments of Anthony Chen’s “Drift.” However, this meditative beginning becomes an omen for the film’s overall impact, which begins with intrigue and slowly but surely gets flooded away.

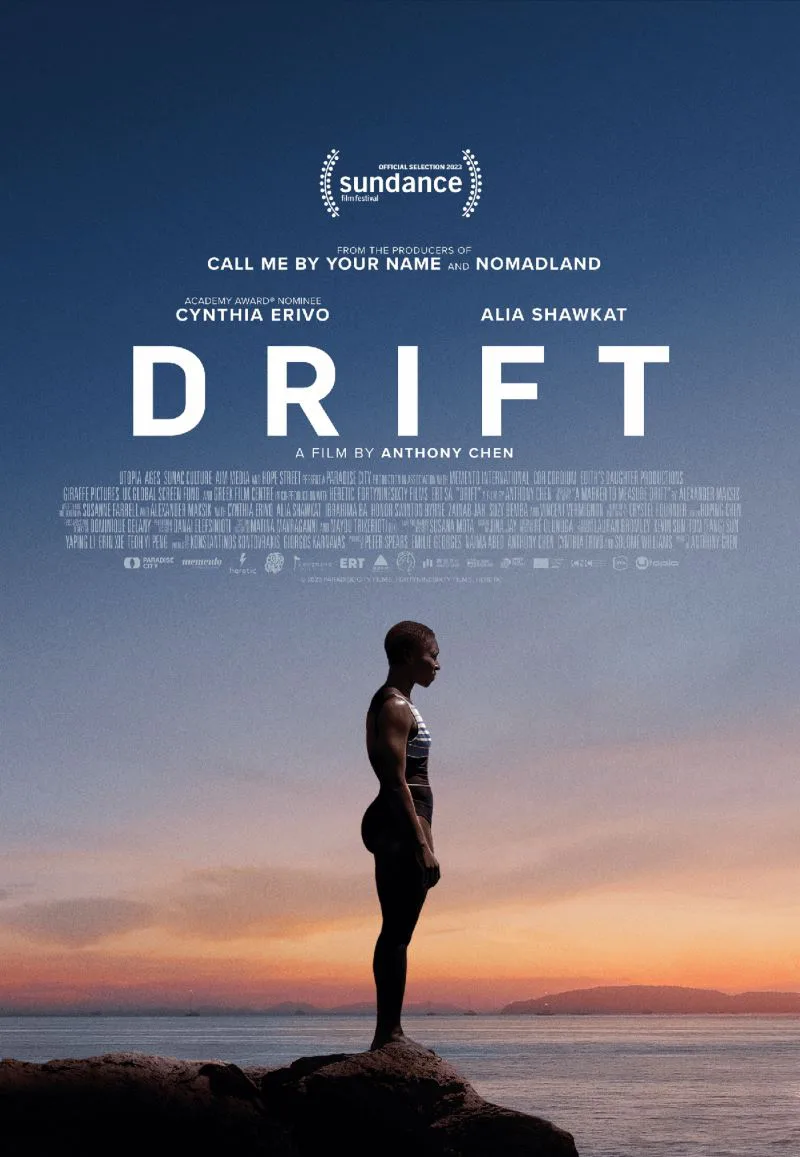

Jacqueline (Cynthia Erivo) is in flux—houseless (and away from home), alone, and vulnerable. She’s a Liberian woman who has found herself in Greece, offering foot massages to tourists on the beach in exchange for a few euros and tucking herself away into unoccupied corners of the waterfront at night to sleep. Chen’s film begins with very little dialogue, just quiet observation as Jacqueline treks through her day, scrounging for meals and aimlessly wandering through time. Through periodic flashbacks we eventually learn that Jacqueline came from a wealthy Liberian family but had been living in London. How did she get to Greece? When a curious tourist asks, Jacqueline replies, “Same as anyone. Plane, ferry … luck.” And that’s the end of that.

It’s simply not enough. Especially given that as these flashbacks progress, we learn that on a visit back home to Liberia, Jacqueline was forced to flee due to conflict, taking nothing but her traumatic memories with her. The film never gives any context as to what this war or conflict is. Unless you’re historically tapped in (or motivated to Google after the film has wrapped), you wouldn’t know about Liberia’s civil war, which ended in 2003. But “Drift” does nothing to establish itself within a time period. There’s no inkling of evidence to suggest that it isn’t present day, and this oversight is glib.

Jacqueline’s trauma is the center of the film, as is her Blackness, but no attention is meaningfully devoted to the details of either. The consequential suggestion is that there would be a lack of curiosity surrounding the context of her war-torn home, and the implication is the monolithic treatment of African countries in media as places ravaged by poverty, violence, or both, and that the depiction comes with no further questions asked. Jacqueline walks the beaches of Greece as a phantom to the privileged white vacationers and a hyper-visible figure to the city’s natives, who immediately clock her trying to sweep food at their restaurants or, as police, stop and question her.

Another African man, Ousmane (Ibrahima Ba) is a constant (at times to unbelievable degrees) popup in her days. Who is he? We don’t know, but he is always attempting to look out for her, even as Jacqueline’s hypervigilance sends her bobbing and weaving through the streets to escape him. The implied attachment is their Blackness, or more specifically Africanness, yet “Drift” treats him as a peripheral symbol or plot device depending on the scene. The true connection of the film comes in the form of Callie (Alia Shawkat), an American tour guide whose open and self-effacing demeanor inspires a relationship that cracks through Jacqueline’s defensive walls.

This relationship, and Jacqueline’s touch-and-go willingness to give in to it, is the most authentic aspect of “Drift.” Through it, we are allotted time with Jacqueline’s vulnerability, and learn about her through how she interacts with others as she slowly allows herself to be known. Given the relationships she’s lost, those of her family as well as her London girlfriend, Helen (Honor Swinton Byrne), “Drift” makes a somewhat eloquent statement about the plague of past lives on future ones and the stagnance that trauma can force. Shawkat also introduces a bit of levity to an otherwise dreary, slow trudge of a film, and scenes with her are a welcome respite. Erivo impressively fulfills the expressiveness required by the film’s limited dialogue, but her character feels cornered by the script’s desire to see her as meek, and even a bit helpless. While the flashbacks give us moments of Jacqueline’s joy, like train rides with her girlfriend or outdoor dances with her sister, they are fleeting and fractional moments compared to her present doe-eyed fear and reactive panic. Perhaps with less questions left unanswered, “Drift” would permit a more sympathetic lead, but the flatness and flippance of its context leaves everything on the surface.

Chen’s voyeuristic direction is a thematic complement to Susanne Farrell and Alexander Maksik’s script, but overall “Drift” has a development issue. It throws nuggets of plot with little information to support it, and between a frustrating lack of understanding and a blase visual style, “Drift” doesn’t compel much engagement. The sparse script is equally light on dialogue and history, crawling in every sense of the word. “Drift” implores you to notice how much effort it’s putting into making you feel, and by consequence, cheapens all of it. Further, in a scant story, it is the moments of dour violence that are treated with the most textual and visual gusto, leaving behind a taste of manipulation and exploitation in a film that claims to be more interested in human aftermath than traumatic impact.