“Donald Cried” is the micro-budget version of a studio man-child comedy, in which an uptight man closely interacts with a free-spirited friend—both of them immature. Low-key shenanigans, like goofy conversations with a couple of odd revelations, ensue. What this movie adds to the arrested development film is a reliance on dialogue, a withholding of large comic set pieces, and a strange title character. But for a movie that seemingly wants a pat on the back for doing things slightly different, it never feels like more than a malnourished Adam McKay movie that lacks even in laughs.

Jesse Wakeman, a co-writer on the project, plays the type of slightly condescending, selfish jerk that Hollywood would dump onto Robert Downey Jr. or a poorly-cast Paul Rudd, venturing back to his Rhode Island hometown to take care of some family business after his grandmother passes. The movie starts with the cringe it so desires in an assuredly unpleasant but cheap way, as his bland, pea-coat and scarf-wearing character (who lost his wallet on the bus) acts too busy for a real estate agent trying to assess his late grandmother’s property, and then asks a friend on the phone to wire him 200 bucks. Outside, he soon runs into his high school friend Donald, who still lives at home, and asks him for money and a ride to the funeral home.

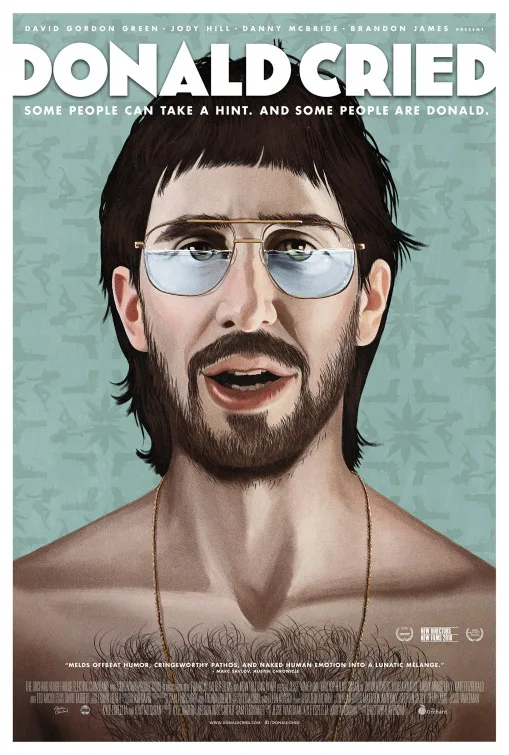

Played by co-writer/director Kris Avedisian, Donald is the one flavor to stand out in this venture, a tall, boyishly-excited dude with a baritone voice and a greasy mullet who talks about the past like how people excitedly recount action movies. He’s a full-force inventor of awkwardness, the way he doesn’t understand social boundaries (like in a cliche gag where he nonchalantly disrobes while uptight Peter is looking at him) or goes on a rant about how Peter’s banking job would be perfect for a future heist. But these characteristics are pitched by the script in such an extreme way, meant to force the awkwardness and test the audience’s sympathy, that he lacks the base of recognition of which his cartoonish nature could then grow from. Instead, he’s more familiar to other fictional characters, offering the expected subtext of sadness while smiling with his huge grin and big, tragic eyes.

The story, of which there is not much, focuses on Donald forcing Peter to hang out, often at Peter’s reluctance (even though Peter keeps asking for money, or a ride). Ultimately, “Donald Cried” remains character-based on these tough-sell fictional beings, observing how things have and have not changed for them. Allusions are made in select dialogue about the past, regarding the stuff they did as metal-heads, and the dead parents in their histories. In particular, Donald proves to have a fascination with Peter, to the point of possible obsession. This last facet might be a sustainably weird element if the story wasn’t so laid-back with the bigger picture.

Even if this were the first, or 50th, movie about the man-child, “Donald Cried” still doesn’t have the vision to make a strong statement. The location of a cloudy, snowy Rhode Island day is a great choice, and there are a couple of inspired visual ideas, like how Donald (in a colorful bathrobe) is introduced by sharing the frame with a garbage can. But there’s an air of sloppiness to this project, the way it often has a blown-out look, or that extended takes of them talking inside Donald’s van or in the snow seem less motivated by striking visuals than economizing serviceable performances. This is the kind of production where the lead actor’s name is spelled incorrectly in the casting credits, as the ending scroll here reads “Avesidian.”

There is something in here about male aggression and sadness, in the way that Peter will engage in rough-housing with the friend he rejects when pushed to like when they wrestle in the snow, or that Donald claims he “lives for” his stepfather beating him up and emasculating him. But in the true spirit of this profoundly uninteresting movie, “Donald Cried” can only shrug through its central notion that men will be sad boys.