Think of a concert film and you think of a camera bolted to the floor in front of the stage and shooting straight up into the singer’s nostrils, which are half-concealed by the microphone. Those films are all right as recordings of song performances, but as cinema they stink. Some directors have broken out of the mold by making documentaries about the event of a concert; the best of those films is still Michael Wadleigh’s “Woodstock” (1970).

Here Michael Ritchie, whose background is almost entirely in dramatic features (“Down-hill Racer,” “The Candidate,” “The Bad News Bears”), tries a new approach. There are times in Ritchie’s Divine “Madness” when he seems to be trying to turn a live Bette Midler stage concert into a Hollywood genre musical. He opens as if “Divine Madness” is going to be a traditional concert film. Bette charges on stage, the audience cheers, there’s an electric performance feel. But from that beginning, Ritchie subtly moves into the material until there are times when we almost forget we’re watching an actual concert performance.

Ritchie’s first decision was to declare an absolute ban on visible cameras. At no moment during Divine Madness do we see any cameras or any members of Ritchie’s crew onstage, even though twenty cameras were used to shoot the performance. Ritchie and Midler used a week of rehearsal to choreograph the camera moves and time them to Midler’s own abundant energy. So instead of looking beyond the performer and being distracted by cinematographers carrying hand-held cameras and sneaking around in their Adidas, we see only the stage, Midler, and her backup singers, the Harlettes. Ritchie also uses camera techniques that are rarely seen in concert films. There are, for example, crane shots in this movie, shots where the camera swoops up to look down on Midler or to circle down and toward her. That’s especially effective during the Magic Lady sequence, in which Bette portrays a sort of dreamy bag lady on a park bench. This sequence comes closest to capturing the feel of a studio musical. That’s not to say that “Divine Madness” loses the impact of a live concert performance. This movie is amazingly alive and involving, and Midler, who has become one of the great live performers, has an energy that steamrollers through an incredible variety of material.

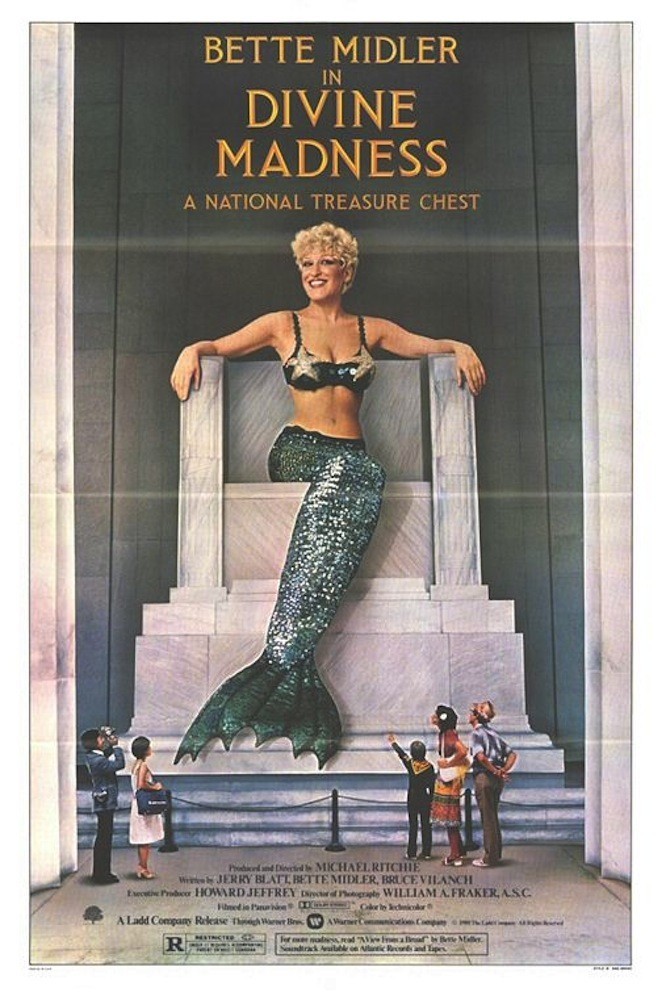

When you think about “Divine Madness” after it’s over, you realize what a wide range of material Midler covers. She does rock n’ roll, she sings blues, she does a hilarious stand-up comedy routine, she plays characters (including a tacky show-lounge performer who enters in a motorized wheelchair outfitted with a palm tree), she stars in bizarre pageantry, and she wears costumes that Busby Berkeley would have found excessive. That’s one reason “Divine Madness” doesn’t drag: Midler changes pace so often that there’s never too much of the same thing.

Is there a weakness in the film? I think there’s one, a curious one. I don’t think Ritchie intercuts enough close-up shots of the audience. That may seem like a curious objection, since I’ve already praised “Divine Madness” for sometimes feeling more like a movie musical than a concert documentary. But you can use people in an audience as characters. Richard Lester did in the original Beatles film, “A Hard Day's Night” (and who can ever forget that blond girl weeping and screaming?).

With a Midler concert, the audience is part of the show. Intercutting selected audience shots with the stage material could have set up a nice byplay in some of the numbers. But Ritchie keeps the audience mostly in long shot; it looks like a vast, amorphous mass out there in the dark. Since the film was actually edited together from three different concert performances, maybe he was concerned about matching audiences. But close-ups would have eliminated that problem.

No matter, though, really. Bette Midler is a wonderful performer with a high and infectious energy level and a split-second timing instinct that allows her to play with raunchy material instead of getting mired in it. She sings well, but she performs even better than she sings: She’s giving a dramatic performance in music, and Divine Madness does a good job of communicating that performance without obscuring it in the distractions of most concert documentaries.