Director Wayne Wang says his favorite image in “Dim Sum” is the sight of the shoes left outside the living-room door in the Tam household in San Francisco’s Chinatown. They are Western shoes, taken off as the characters enter a home that is still run according to Chinese values by old Mrs. Tam, a sweet widow with a strong but quietly concealed will. After the success of “Chan Is Missing,” his first slice-of-life about Chinese-Americans, Wang was looking for another story, and when he saw some shoes left outside a Chinese home, he knew he had his viewpoint, and only had to create his characters.

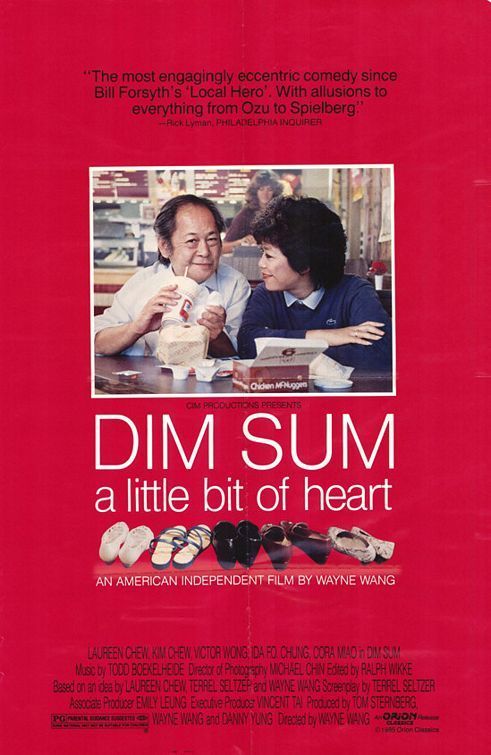

He has created some unforgettable ones, including Mrs. Tam (Kim Chew), a 60ish woman whose husband is dead and whose children have left home, all except for the youngest daughter; Geraldine Tam (Laureen Chew), the daughter, who says she wants to get married but feels she should stay with her mother, and Uncle Tam (Victor Wong), a jolly, worldly bartender who would marry Mrs. Tam if Geraldine would only get out of the way.

These three characters dance a subtle little emotional ballet during the film, as we gradually become aware of their true motives. Mrs. Tam is given to sadly shaking her head and bemoaning the fact that her daughter is 30 and still single, but there are clues that she enjoys the fact that Geraldine has stayed at home with her. That way, she will not have to deal with Uncle Tam, who, for that matter, may only be paying lip service to his desire to marry her. Meanwhile, Geraldine has a boy friend in Los Angeles who has been waiting patiently to marry her, and perhaps Geraldine uses her mother as an excuse to avoid the idea of marriage.

What is remarkable is the way Wang deals with this complex set of emotions, in a movie that is essentially a comedy. Some of the scenes in “Dim Sum” are as quietly funny as anything I’ve seen this year, especially Mrs. Tam’s birthday party, a long conversation she has over the back fence with a neighbor, and the way Uncle Tam effortlessly mixes his Chinese wisdom with the lessons he has learned as a bartender.

The movie is not heavily plotted, and that’s good; a heavy hand would spoil this fragile material. Wang’s camera enters quietly and observes as his characters lead their lives, trying to find a compromise between too much loneliness and too much risk. At the end, everyone is more or less happy, and more or less sad, and in this movie that is satisfactory.

Note: Although this is no doubt not what Wang had in mind, I couldn’t help thinking, as I watched “Dim Sum,” that the movie’s characters and situations could be effortlessly spun off into a wonderful TV sitcom.