Thomas Vinterberg’s “Dear Wendy” is a tedious exercise in style, intended as a meditation on guns and violence in America but more of a meditation on itself, the kind of meditation that invites the mind to stray. Mine strayed to the fact that the screenplay is by Vinterberg’s Danish mentor Lars von Trier, and the movie, although filmed on three-dimensional sets, feels as artificial and staged as Von Trier’s “Dogville” (2003). Once again, a small group of people inhabit a small space, can all see each other out the window and live in each other’s pockets.

The movie is set in Electric Park, a set in which two rows of buildings face each other and a third row supplies the end of the street. Towering overhead is the elevator for the mine shaft; the locals were mostly miners, but the mines are nearly played out. Dick (Jamie Bell), the orphaned son of a miner, lives with his protective black housekeeper, Clarabelle (Novella Nelson), and his life lacks purpose until he goes into a store to buy a toy gun.

The weapon, as it happens, is real. Dick is a pacifist but falls in love with the gun, which he names Wendy. Much of the movie consists of a letter he writes to Wendy, about how he loved her and lost her, and how everything went wrong. He descends into an abandoned mine for target practice, finds he has a psychic bond with Wendy (he can hit a bull’s-eye blindfolded) and soon enlists other people his age into a secret society named the Dandies.

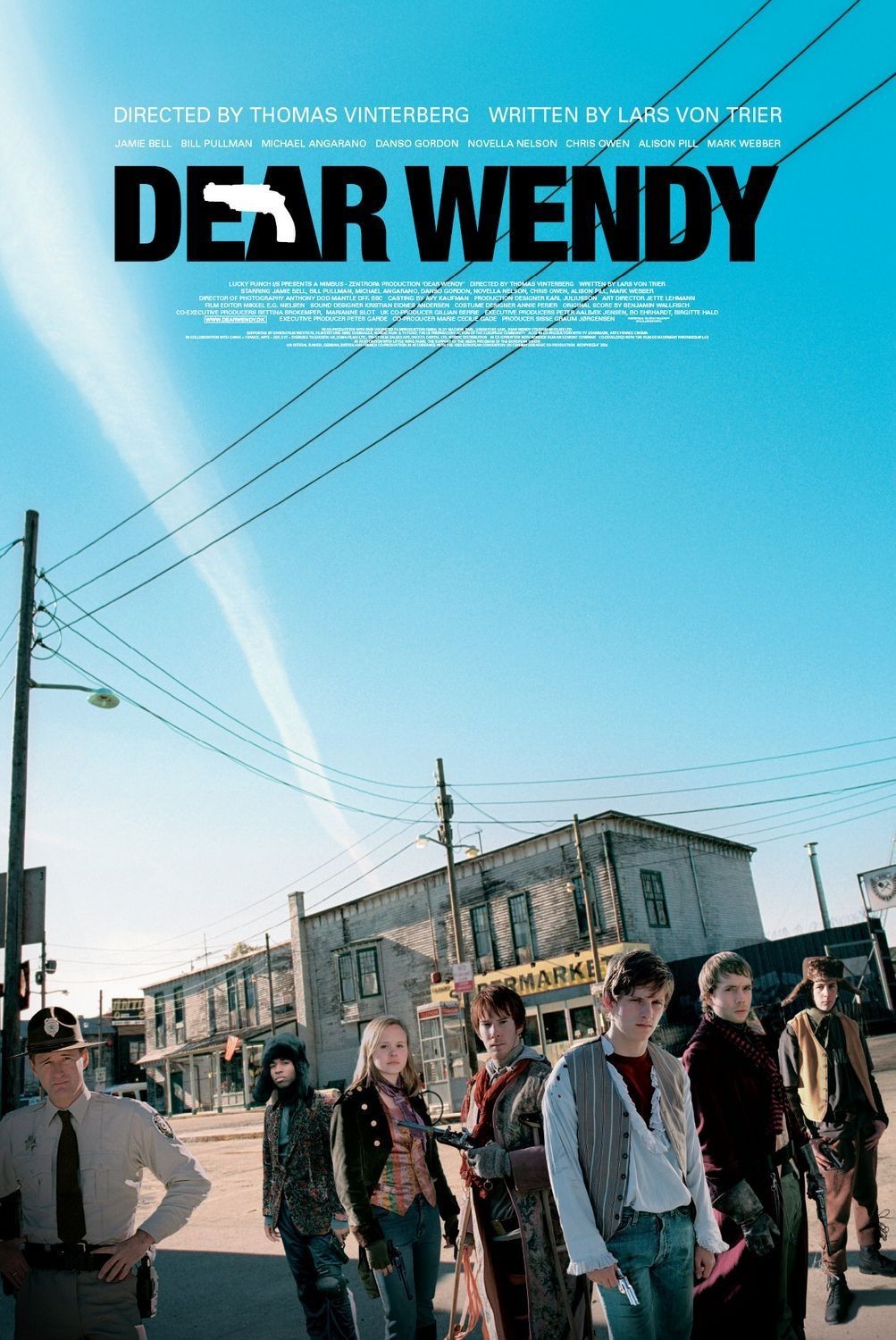

They meet in the mine, which they redecorate as the “Temple,” and begin to dress in oddments of haberdashery, like fools or clowns. They have the obligatory unlimited supply of candles. They take a vow of non-violence. Then Clarabelle’s grandson Sebastian (Danso Gordon) appears on the scene, fresh from jail. The local sheriff (Bill Pullman) suggests that Dick “could be like Sebastian’s friend, and keep an eye on him.”

Sebastian is black because he is Clarabelle’s grandson, of course, but also because as the only young black man in the play, he is made into the catalyst for violence. This is the Vinterberg/Von Trier version of insight into America, roughly as profound as the scene in “Dirty Love” where Carmen Electra holds a gun to a man’s head simply because she likes to act black and thinks that will help. To call such reasoning racist is tempting, and yet I suspect in both movies the real reasons for it are stupidity and cluelessness.

Right away there is trouble. A romantic triangle forms, as Sebastian holds Wendy tenderly and Dick gets jealous. Sebastian helpfully supplies all of the Dandies with guns, and then a challenge emerges: Clarabelle visits her granddaughter at the end of the street every year and has become afraid to leave the house. The Dandies devise an ingenious scheme to protect her from danger during her one-block walk, despite the fact the town seems to contain no danger. I am reminded of a guy I knew who said he carried a gun because he lived in a dangerous neighborhood, and another guy told him, “It would be a lot safer if you moved.”

What happens during Clarabelle’s progress down the street I will leave for you to experience if you are unwise enough to see the film. As the Dandies plan their operation, Dick draws a diagram of the town that looks uncannily like an aerial view of the chalk outlines on a sound stage floor that Von Trier used to create Dogville. Odd, that the Dogma movement from Denmark, which originally seemed to call for the use of actual locations exactly as they were, has become more stylized and artificial than German Expressionism.

It is true that America has problems, and that many of them are caused by a culture of guns and violence. It is also true that a movie like David Cronenberg’s “A History of Violence” (or I could name countless others) is wiser and more useful on the subject than the dim conceit of “Dear Wendy.” Apart from what the movie says, which is shallow and questionable, there is the problem of how it says it. The style is so labored and obvious that with all the goodwill in the world you cannot care what happens next. It is all just going through the motions, silly and pointless motions, with no depth, humor, edge or timing. Vinterberg has made wonderful films like “The Celebration” (1998), filled with life and emotion. Here he seems drained of energy, plodding listlessly on the treadmill of style, racking up minutes on the clock but not getting anywhere.