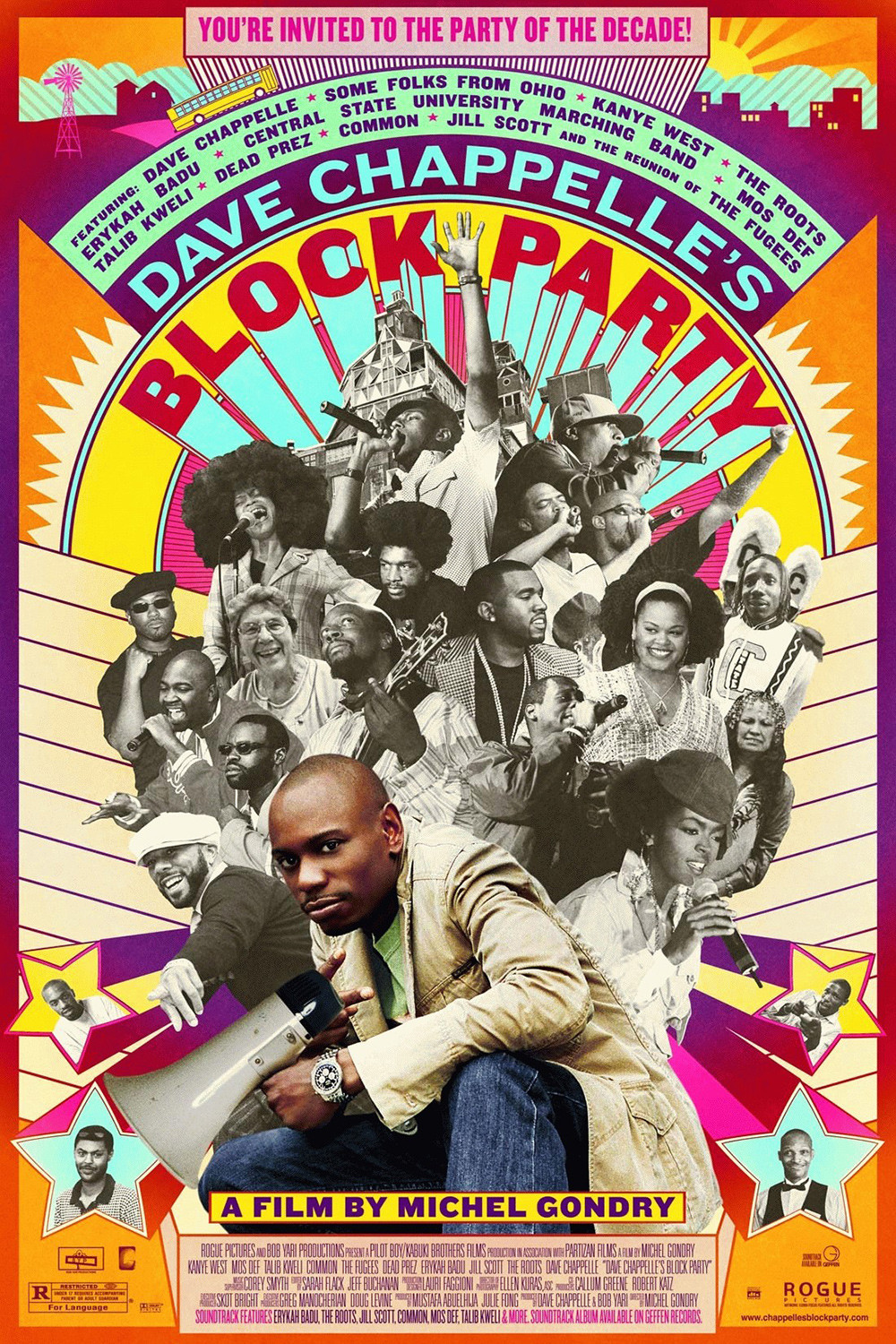

“Dave Chappelle’s Block Party” is a fairly disorganized film about a fairly disorganized concert, redeemed by the good feeling. Chappelle sheds like a sunbeam on every scene. I came away from the movie with three observations: (1) I find a lot of rap nihilistic and negative, but the musicians featured here seemed accessible and positive; (2) Nevertheless I was pathetically grateful when Lauryn Hill and the Fugees sang “Killing Me Softly With His Song” and when many of the others sang what used to be called songs. Thank God for melody. (3) Dave Chappelle appears to be a nice man, in addition to being a funny one, and the buried message in this movie may be: “Can I sign a $50 million contract and still remain the person I am happy to be?”

The movie is a documentary about Chappelle’s sudden inspiration to hold a rap and comedy concert at a free block party in Brooklyn. The location would be kept secret to avoid a mob scene, and the audience would include people from the block and others who were bussed in. And by bussed in, I mean from Dayton, Ohio, which is about 20 miles from Yellow Springs, where Chappelle lives. The film opens with him handing out tickets good for a bus ride, a hotel room, food and admission to the concert. He offers them to the nice lady who runs the shop where he buys his cigarettes, and to a couple of young men on the street, and to a man who says he is too deaf to hear the music, and then, in an expansive mood, he invites the entire Central State College Marching Band. (The two young men from Ohio stand on a rooftop and say now they really feel they’re in New York, because in the movies everybody is always standing on rooftops.)

That some of the lucky ticket winners are white and even middle-aged is part of the point: He wants them to come to a rap concert in Brooklyn, and he wants it to be a rap concert where everybody will feel at home. In this connection the musicians do not reflect a gangsta image, use lyrics that are not particularly hostile or angry, and employ the N word, the F word and the MF word only about every 20 words, instead of every fifth word.

On the stage is an all-star cast, including Mos Def, Erykah Badu, Kanye West, Talib Kweli, Dead Prez, Jill Scott, the Roots, Bilal, and Lauryn Hill with the reunited Fugees. If I told you I knew who all of them were, I’d be lying. The women (Badu, Scott, Hill) seem to please the crowd more than the men, maybe because their material leans more toward jazz and R&B. Mos Def is a surprise, because a day earlier I’d seen him co-starring with Bruce Willis in “16 Blocks,” a movie where his character talks incessantly in a high-pitched screech; on stage with Dave, he’s got an entirely different personality, a different voice even, and seems cool, authoritative, likable. Kanye West you know about, and he wears his superstardom lightly.

There is an audience for rap and, let’s face it, I am not a member of that audience. That’s why I was surprised to enjoy so many of the performances in the film. Not that I am likely to become a convert. As I write this, I’m listening to the Dianne Reeves soundtrack album from “Good Night, and Good Luck,” and it is wonderful. Not that you are likely to become a convert. Maybe we can meet in the middle.

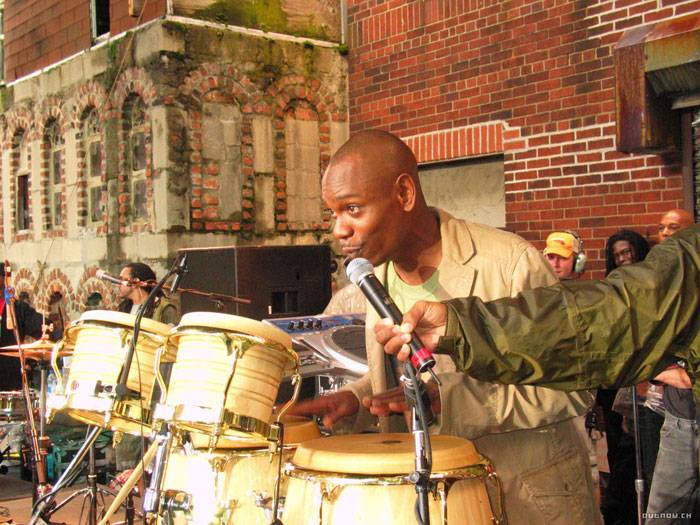

The concert doesn’t exactly proceed like clockwork, and it doesn’t help (or hurt much) that it rains. Chappelle is on stage most of the time, does a lot of spontaneous comedy, makes the crowd feel good. There is a lot of backstage footage of Chappelle talking about how the concert will go, how it is going, and how it went. He has a theory about musicians and comedians: All comedians wish they were musicians, and all musicians think they are funny. “I’m mediocre at both,” he says, “but have managed to talk my way into a fortune.”

It’s that fortune that seems to be the problem. The concert was held on Sept. 18, 2004. It was on Aug. 3, 2004 that Chappelle signed his infamous $50 million contract with Comedy Central. In this movie, long before his “disappearance” and his confessional with Oprah, you can see those millions nagging at him. His block party seems like an apology or an amends for the $50 million, an effort to reach out to people, to protect his ability to walk down the street like an ordinary man.

Having watched Chappelle on his show, on “Oprah” and now in this movie filmed at the dawn of his life as the $50 Million Man, I get a sense for how he feels. There is something about a $50 million contract that feels wrong to him, that threatens to build a wall between his personality and the way he likes to use it. His Comedy Central show is (was?) so funny because he worked without a net. He was willing to try anything. He didn’t obsess about whether it worked. Here he makes some ominous comments about executives and you intuit he’s saying that the Dave Chappelle Show will never work if anyone other than Dave Chappelle has a license to provide input.

As for the movie, I’ve seen better comedy films and better concert films. It noodles around too much and gets distracted from the music. Michel Gondry, who directed, makes good fiction films (“Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind“) but is not an instinctive documentarian and forgets that even a fly on the wall should occasionally find some peanut butter. As the record of a state of mind, however, the film is uncanny.