“What Dali has done and what he has imagined is debatable, but in his outlook, his character, the bedrock decency of a human being does not exist. He is as anti-social as a flea. Clearly, such people are undesirable, and a society in which they can flourish has something wrong with it.” So George Orwell pronounced, in 1944, in an essay that was ostensibly a review of Salvador Dalí’s autobiography. Orwell is so frequently (and in many instances inaccurately) cited these days as a kind of secular prophet and ideological saint that it’s often forgotten that he was also a bit of a prig.

Like many boys my age—okay, maybe not—I was a big Dalí fan in the late 1960s. I’m still awestruck by his 1931 painting The Persistence of Memory—yup, the melting clocks one—not just because of the genuine numinosity of the image but the craft. It really is meticulous, and on such a small canvas! It’s only nine by eleven inches. Its realistic components—the cliffs in the background—are beautifully detailed but not photorealistic. Rather, like the details in Rockwell—I think he’s good, too!—they’re poetically realistic. And while I’ve since grown to admire Max Ernst more than Dalí as far as surrealists go, I still dig the guy while acknowledging that his work, while maintaining a high standard of craft, didn’t reach the “real thing”ness of Memory too often throughout his subsequent career. But he never stopped irritating people.

By the 1970s, Salvador Dalí was more than a provocative painter. Like his pop art then-contemporary Andy Warhol, he was a brand. A self-willed one, too; years before his Surrealist confrere sought to condemn Dalí with the anagrammatic nickname “Avida Dollars,” which the artist practically embraced. He and his wife Gala cast themselves as monied socialites, and while they did not make the acquaintance of Don Henley—as this movie depicts, shock-rocker Alice Cooper was more their speed—they threw outrageous parties and paid outrageous bills.

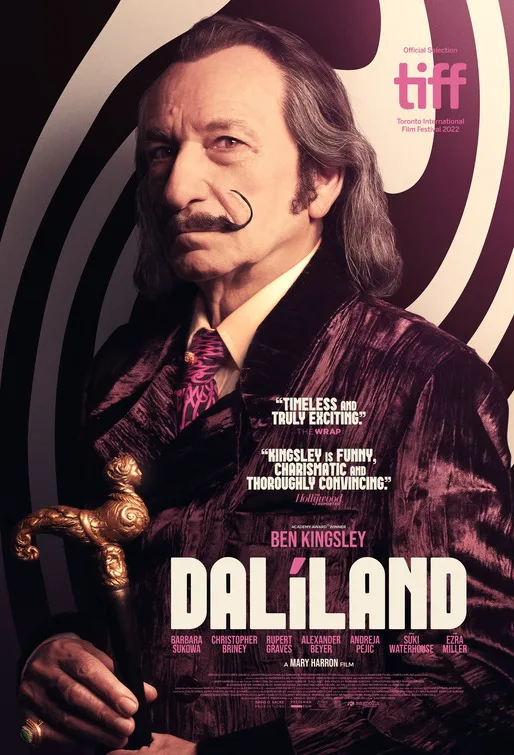

Or did not pay them, depending. “Dalíland,” directed by Mary Harron (“I Shot Andy Warhol,” “American Psycho”), shows the 1970s Dalí through the eyes of one James Linton. The frame story is the early ‘80s, after a disastrous electrical fire at a residence in Spain practically fries the now-widowed Dali. James, watching a report on television, is borne back into the past. Fresh out of an Idaho art school, now an assistant at the New York gallery repping Dalí, hunky James (Christopher Briney, who’s appealing and also, well, appealing) is sent to look after Dalí as he prepares for a show. Or is he meant to be a bait for Gala, who, James is told, has the libido of an electric eel? Hard to say. What is evident is that Dali’s social whirl is dizzying. There’s Alice Cooper, there’s Amanda Lear, the leggy model who may be a transsexual woman (played here by Andreja Pejic, who definitely is), there’s a guy called “Jesus” who’s really Jeff Fenholt, who’s in the Broadway company of Jesus Christ Superstar And there’s Dalí, who holds forth on whether he created God or God created him and tells of his plans to construct a globe-spanning giant penis as his “contribution to world peace.” He seems exhausting.

Dalí is portrayed by Ben Kingsley in the main story and by Ezra Miller in flashbacks to Dalí’s youth. Not to make light of Ezra Miller’s troubles, but one thing both actors have in common is, for lack of a better phrase, mad charisma. And Kingsley adds dimension to that in the scenes in which Dalí’s willful quirks and taxing eccentricities run headlong into the mishaps and infirmities of old age. As Gala, Barbara Sukowa is the stealth MVP of the movie, her wounded pride going in a straight line back to when she walked the street of Paris “until my shoes filled with blood” looking for a dealer to sell Dalí’s paintings. Now in a fierce state of ego decrepitude, she sponsors the no-talent Fenholt (who can’t even keep his electric guitar in tune) while grudgingly tending to her husband.

The smarts this movie sometimes shows tend to underscore how this is Harron’s most conventional biographical consideration. The script, by John Walsh, features a subplot derived from “Almost Famous” in which a female Dalí groupie (dubbed “Ginestra” by the artist—her real name is Lucy—just as James is called “San Sebastian” by his eminence) tells James, “My father thinks Dalí is a pornographer which I love,” before sexually initiating him into the clan. Ducking a date for dinner with Dad, she clucks, “I have to make an appearance, or else my father won’t keep paying my rent.” Ar ar ar. I know people of this sort existed and still do, but surely there must be fresher ways of writing them. Suki Waterhouse does her best with what she’s given. But still. The movie’s commonplaces don’t serve its singular subject—love him or hate him—all that well.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.