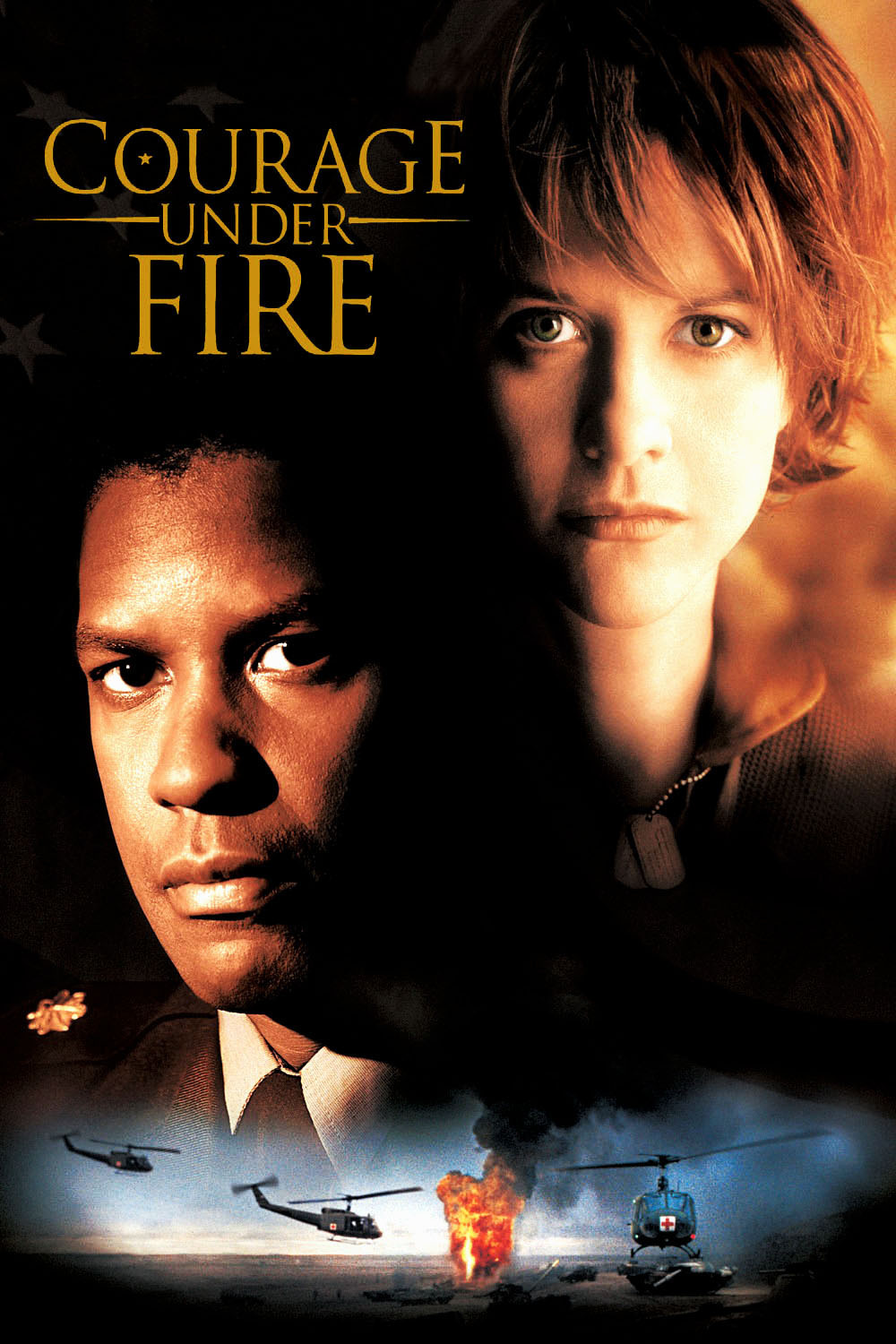

Eyewitnesses are notoriously unreliable, even when they want to tell the truth. As an Army lieutenant colonel reconstructs a battle scene in “Courage Under Fire,” he begins to suspect that some of his witnesses are lying. His assignment: decide on the suitability of the first woman ever nominated for a Medal of Honor. His problem: The White House is salivating over the media image of presenting the posthumous medal to the woman’s young daughter, in a ceremony in the Rose Garden.

The colonel, named Serling and played by Denzel Washington, is determined to do his job honestly and well, even though his own life is falling apart. During a night tank battle in the Gulf War, he was indirectly responsible for taking out an American tank with friendly fire. An Army investigation excused him, but now his sleep is fragmented by nightmares, he’s drinking too much, and he has moved out on his wife and children. The investigation is about the only thing holding him together.

The woman under consideration for the Medal of Honor is Capt. Karen Walden (Meg Ryan), who commanded a helicopter in the battle zone. After taking out an enemy tank by the refreshing improvisation of dropping a fuel tank on it, Walden’s chopper was shot down by enemy fire. Nearby American troops heard M-16 fire, apparently by the wounded Walden, that kept the enemy at bay the next morning, until her men could be rescued. For this she certainly deserves the medal–if that’s how it happened.

Edward Zwick and Patrick Sheane Duncan, the director and writer, construct their screenplay with a nod to “Rashomon” (1950), Akira Kurosawa’s famous film in which four defendants give their wildly different testimony about a murder. In “Courage Under Fire,” the witnesses are Walden’s own men. Ilario (Matt Damon), the medic, paints Walden as a brave leader sacrificing her life for her men. Monfriez (Lou Diamond Phillips), the gunner, says, “She was afraid, Colonel. She was a coward. That’s the bottom line on your Capt. Walden.” Another crew member, Altameyer (Seth Gilliam), languishes in a veterans’ hospital, confused by painkillers.

Serling, the Denzel Washington character, doggedly conducts his investigation by day and spends his nights boozing in hotel bars. He is being tracked by a reporter for the Washington Post (Scott Glenn), who suspects there was a cover-up of the tank destroyed by friendly fire. Serling tries to avoid him, but Serling is a man who desperately needs to tell the truth to someone, and the reporter is relentless.

These interlocking investigations all take place under the thumb of the unrelenting Gen. Hershberg (Michael Moriarty), who wants the friendly fire incident kept quiet and the Medal of Honor approved (there is urgent pressure from the White House). Hershberg turns the screws, threatening Serling’s Army promotion path and hinting at reprisals (“I know about the drinking”).

“Courage Under Fire” is Hollywood’s first film about the Gulf War, and one of the rare films to deal with women in combat. But it is not simply a war film; there are also personal issues involved, and the story does a good job of dealing with the relationship between Serling and his wife (Regina Taylor), who tells him she will wait for him–but not forever.

Washington’s role is the central one, and he handles it well, playing a man who sticks to procedure and self-discipline even in the midst of emotional chaos (before the tank battle, he leads his men in prayer, and then adds, “Now let’s kill ’em all!”). Meg Ryan‘s role is a different kind of challenge: In the flashbacks through the eyes of her men, she is seen in three or four entirely different styles of behavior. The movie doesn’t give us one Capt. Walden but several, for us (and Serling) to choose among.

Zwick’s direction handles the many conflicting story possibilities with great clarity. And the opening sequence, involving the mistaken tank attack, makes it clear how confusing battle is, and how differently it will be perceived by each participant. The end of the film understandably lays on the emotion a little heavily, but until then “Courage Under Fire” has been a fascinating emotional and logistical puzzle–almost a courtroom movie, with the desert as the courtroom.