“Corrina, Corrina” has its heart in the right place, and its characters are some of the nicest people I’ve met at the movies lately, but the movie seems to exist under a cloud of gloom, and I kept hoping for sunshine.

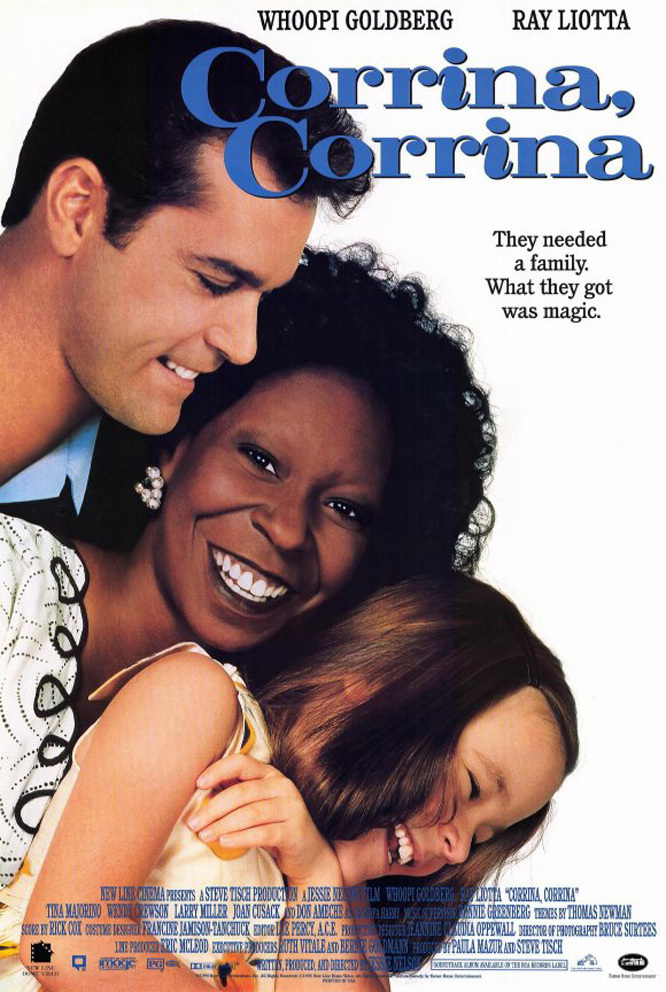

The story involves Manny Singer (Ray Liotta), a jingle writer for an advertising agency, whose wife has died, leaving him with a 7-year-old daughter named Molly (Tina Majorino). He desperately needs a nanny, and interviews several applicants, all deeply flawed in the ways Movie Reject Nannies always are, before settling on Corrina Washington (Whoopi Goldberg).

The time is 1959, and the movie implies that Corrina, a recent college graduate, can’t find any other job because she is black. She is overqualified for this one, but has many qualifications for being Manny’s partner in life, one of them being her suggestion to take the “t” off of “shouldn’t,” so it rhymes with “puddin,” and he wins the Jell-O account.

The Singer household is a cavern of gloom when Corrina first enters it. Molly has decided to stop talking, and Manny spends most of his time looking dazed and confused, and smoking too many cigarettes. Corrina smokes, too, and this leads to a lot of intimate cigarette behavior, in which the two adults, shy about communicating in other ways, light up together. They also spend a lot of time discussing jazz. (There is a running gag about how Molly is stealing their cigarettes because she heard a government health warning on TV; the movie would have been improved by the elimination of this subplot, with its cutsey payoff.) The opening hour of the film is morose and sad, as the two adults and the child create a series of small social embarrassments, awkwardnesses, and apologies. But Corrina is slowly able to win the little girl’s trust, and soon she is talking again. The plot contrives for Corrina to find herself staying over for dinner on several occasions, and Manny is surprised at her comments about music and literature. There are also well-written philosophical discussions between Corrina and Molly, who blames herself for her mother’s death. A family unit is obviously being formed here, and there’s a nice little moment when Manny is hurrying out the door and Corrina gives Molly instructions, and Manny blurts out, “Listen to your mother!” Molly smiles secretly at that, because she has determined that Corrina should, indeed, marry her daddy and move in full-time.

It takes the adults longer to figure that out, and the screenplay, by director Jessie Nelson, seems sort of shy about the emotional details. Liotta plays Manny as closed-off and absent, and Goldberg plays Corrina as prescient and tactful, and eventually the two find themselves in each other’s arms-but more through a logical decision, somehow, than because of love or passion.

The movie has a lively subplot involving Corrina’s home life; she lives with her sister and her sister’s kids, who become Molly’s playmates. The energy in this household provides some needed sunshine, but the movie also supplies the usual obligatory scenes in which Corrina’s sister, Manny’s mother and a nosy neighbor all express their disapproval of interracial romance. Those scenes seem almost pro forma; there’s no real emotional confrontation over the subject, and indeed the whole movie seems kind of muted.

There’s a lot I liked in the film, including the intelligence of some of the dialogue, but “Corrina, Corrina” seemed to be trying to do both too much, and too little. It deals with death, loss, healing, romance and communication, but in ways that are predictable, however well-handled. And it seems almost as shy as the characters about the charged issues of race and romance. After it was over I felt that, yes, it was warm and good-hearted, but there was more of a story there to be told.