The world of the standup comedian is filled with a special desperation. He needs to win your approval at every single instant. If one joke goes bad, a silence falls, and up on the stage that silence sounds like a roar of disapproval. He will say anything to make you laugh. It should not be surprising, then, that standup comedy is the worst possible training for an actor. The case of Robin Williams is a good example.

On the stage, he is very funny. On television and in certain movies, where he is given a well-defined character and forced to play him, he is not only funny but can be moving, as he was in “Moscow on the Hudson.” But left to his own devices, he will go for the quick laugh every time and create a shambles out of his character, the plot, the movie and anyone within firing range. I wonder what he’s trying to do. Make the camera crew laugh? Consider “Club Paradise,” Williams’s new movie. He plays a Chicago fireman who wins a big disability settlement and moves to the Caribbean to run a shabby resort club. The movie opens with the big fire where he risks his life and is blown out of a third-floor window. After the credits, the rest of the movie takes place at the resort. The credits aren’t long, but they are long enough for the Williams character to drop every shred of credibility as a Chicago fireman.

He develops one of those Canadian quasi-British accents, starts with the one-liners, makes small talk with the British governor general, trades quips with soci ety people and looks as if he would use a whoopee cushion if he had one. There are scenes that play like he’s standing around trying to think of something clever to say. He sometimes seems to be the movie’s guest host instead of its star.

The film was directed by Harold Ramis, the onetime Second City resident. He made a big contribution to “Ghostbusters” as co-writer and star, but he has been more erratic as a director (“Caddyshack,” “National Lampoon’s Summer Vacation”). He comes out of a revue tradition, where you try for something terrific right now and forget about what lies minutes in the future. Maybe he encouraged Williams; in “Caddyshack,” it seemed to work when Rodney Dangerfield did his standup act.

What happens in “Club Paradise,” however, is that the movie lives so firmly in the moment that it never develops any energy for its story. There’s nothing for us to really care about. The screenplay is broken down into schtick so that characters can materialize, do their thing and evaporate. The most notable victim of this approach is Peter O'Toole, who plays the dissipated British governor-general of the island. He appears, gives us a taste of a potentially great comic character and then is never really exploited.

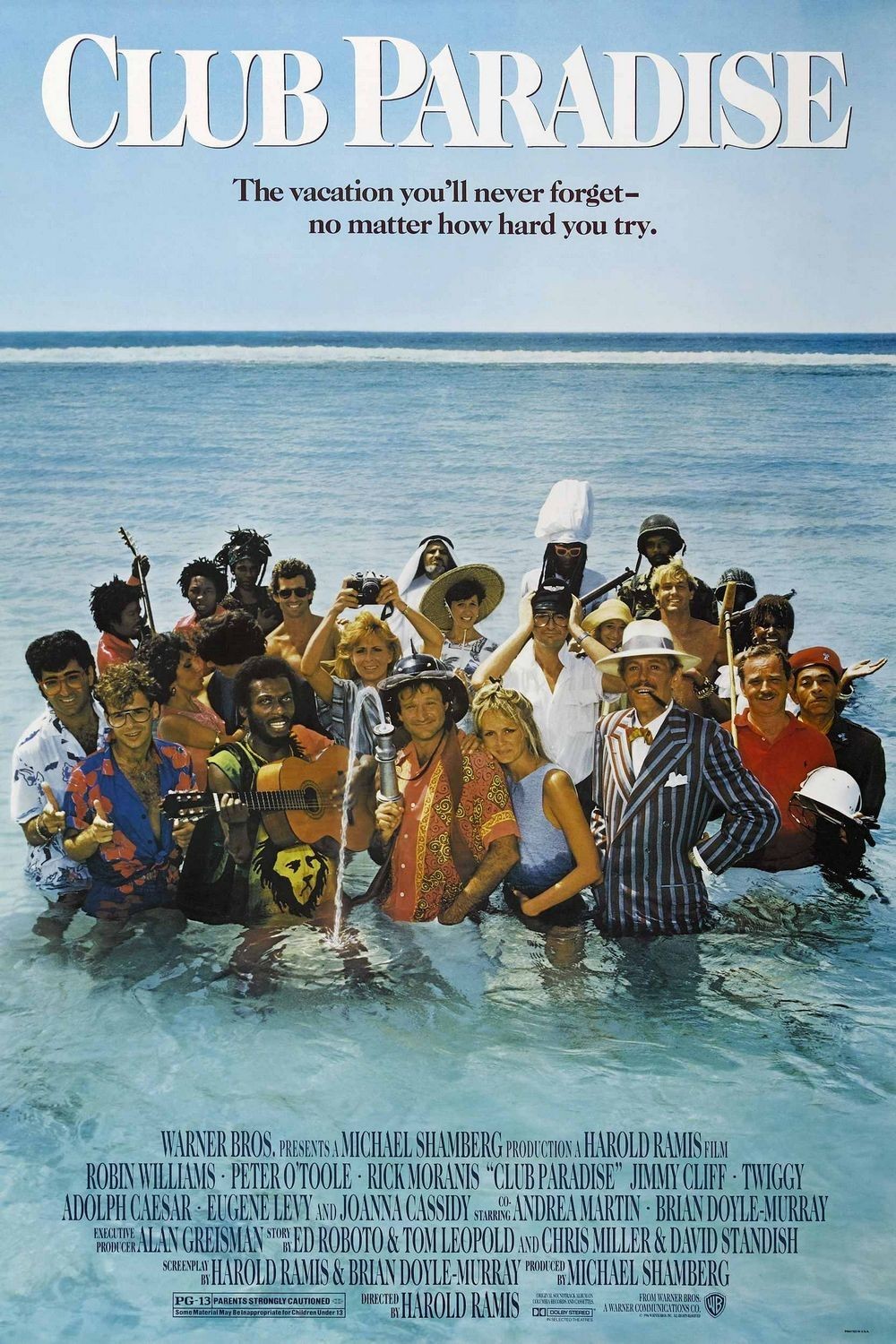

The situation: Williams plays host to a planeload of cut-rate tourists, who represent the usual cross section of ethnic types and behavioral hangups. Meanwhile, trouble brews on the island as an independence movement picks up steam. Jimmy Cliff, the reggae singer, plays an entertainer who is a leader of the movement, and Adolph Caesar is the pompous prime minister beneath O’Toole’s bleary-eyed figurehead rule. (This was the last performance by Caesar, the Oscar nominee for “A Soldier's Story,” who died late last year.) While the revolution brews, the tourists party.

Ramis’s cast includes a convention of Second City graduates: Eugene Levy, Brian Doyle-Murray, Joe Flaherty, Mary Gross and Bill Curry. They have their moments, especially Levy as an uncle who has brought his nephew along to the island and teaches him the fine points of lechery and voyeurism.

But the movie never really comes together, and I think the fault for that begins with Williams. When the star of a movie seems desperate enough to depend on one-liners, can the rest of the cast be blamed for losing confidence in the script?