There was a time in the 1970s when Lina Wertmuller briefly seemed to be the new hope of European cinema. After movies like “Love and Anarchy,” “Swept Away . . .” and “Seven Beauties,” she was even profiled in a famous New York magazine cover story by John Simon, who found her, as I recall, just about the best living director. Then she lost whatever magic she had, and the 1980s were a dismal time in her career.

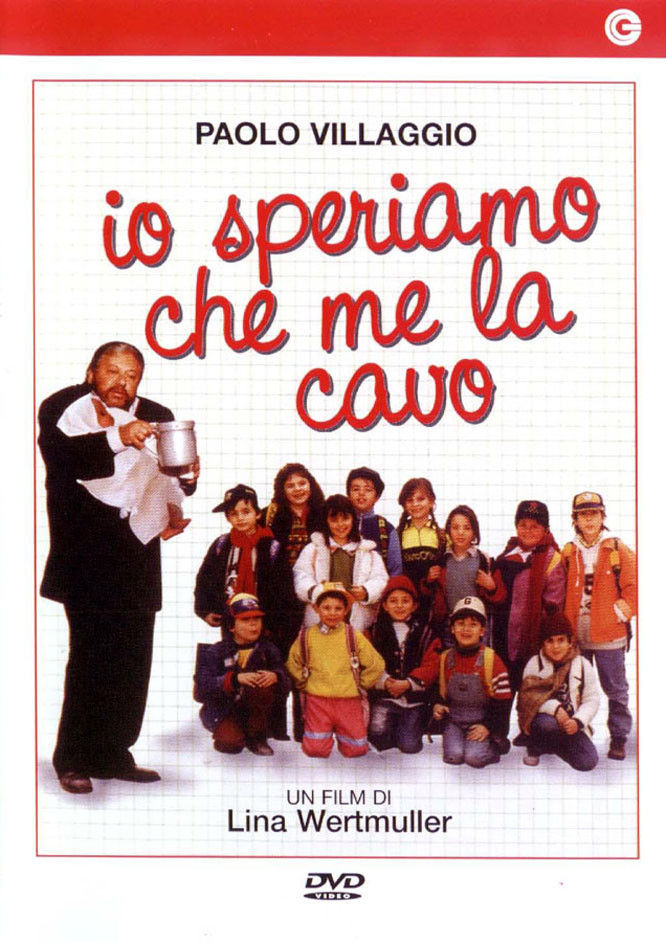

Now she is back with a movie like “Ciao, Professore,” which has undeniable qualities, although none of them are what made Wertmuller famous.

There is little sardonic wit, little irreverence, little satire here; the movie seems inspired more by the sentimental “Cinema Paradiso” than by Wertmuller’s early films.

The hero is the “Professore,” a grade school teacher from northern Italy who has been assigned, through a bureaucratic error, to the shabby De Amicis School in a poverty-stricken village near Naples, named Corzano. He immediately puts in a request to be transferred back to the more affluent district he is accustomed to, and meanwhile surveys the disaster area he has inherited.

No one ever seems to quite attend classes at the De Amicis school. The principal, an officious woman, is not even really in charge; the true power seems to be the janitor, who has Mafia connections and charges the children for such staples as toilet paper.

The Professor soon figures out that most of the boys in his class are absent because they are at work – either helping their fathers in the family businesses, or as free-lancers. He makes a tour of the village, collecting the children, pulling them out of shops and away from newsstands, and marching them back into the classroom.

Then he has to deal with the usual problems of an unruly class, and he employs such age-old movie cliches as (a) actually being nice to them; (b) being firm; (c) challenging the ringleader, and (d) getting them interested in their lessons.

The movie adopts the pious assumption that school is, of course, better for the children, but actually the village of Corzano seems such a riot of vibrant life that there were times when I wondered whether the children wouldn’t have been better off staying in the streets. Everyone seems to know everyone else’s business; the staircases outside tenements are stages on which life’s daily theater is played; and the children, especially the ringleader Raffaele (played by Ciro Esposito), seem bright with the wisdom of the city instead of dim with the lessons of dutiful students.

There is of course a crisis, a dark night of the soul, for the Professor. And a redemption. And a class trip (no school movie is complete without one). And the movie doesn’t end exactly as I would have anticipated; Wertmuller gets points for a conclusion that seems more real than manufactured.

But the movie seems somehow unfinished. All of the events are there, and the colorful locations, and the personalities of the characters.

But what is this movie about? With Wertmuller, we would assume some higher purpose than simply an Italian version of a story that has been filmed in every country on earth. Some twist, or angle.

But there is none. “Ciao Professore” is a sweet movie with some lovable characters in it, but there was a time when Wertmuller would have snorted in scorn at the simplicity of this material, and gone to work to make it her own.