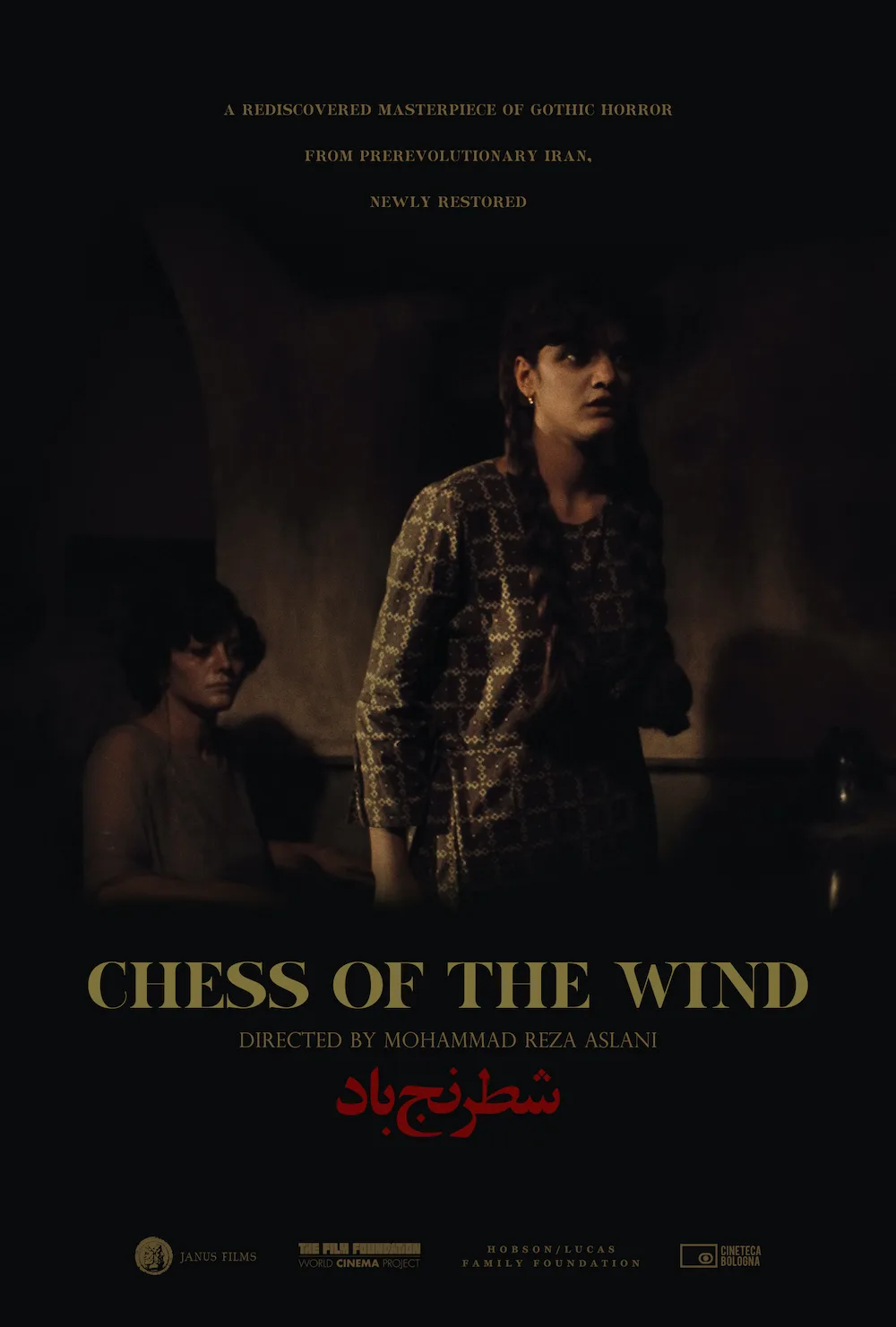

Lost films reappear from time to time and receive their critical due, places in the canon and, occasionally, a measure of popular acclamation. But seldom do we see a cinematic resurrection as astonishing and impressive as that of Mohammad Reza Aslani’s “Chess of the Wind.” Met with critical hostility and audience indifference when it premiered in Tehran in 1976, the ravishing period drama was banned by the Islamic Republic and considered lost until 2014, when the director’s son discovered a can containing a print of the film in a junk shop. Now restored under the aegis of Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, it enters theaters this week as that unlikeliest of revelations: a nearly 50-year-old masterpiece virtually unknown till now.

A poet and production designer who had made short documentaries, Aslani was just 32 when he launched his narrative feature debut with “Chess of the Wind” (it was shown at last year’s New York Film Festival as “Chess Game of the Wind,” a title that makes a bit more sense). Perhaps if he’d been older and more established, the film would have received a more attentive and appreciative reception, but its lack of contemporary renown still surprises, because even measured against the Iranian and international cinematic treasures of the ‘70s, Aslani’s vision is still breathtakingly distinctive, an incisively devastating social critique embedded in a complex tale of intrigue, greed, oppression, and murder. The film is also, and perhaps most strikingly, a stylistic tour de force.

The story is set in the early 1920s, the last years of the Qajar dynasty, which had ruled Iran since the 18th century and set new standards of decadence as its end approached. Aslani’s film premiered three years before the end of the dynasty that succeeded the Qajars, the Pahlevis, and no doubt Iranian audiences would have understood that the earlier era was meant to implicate the decadence of the current monarchy. In fact, many Iranian films of the 1970s were rife with feelings of gloom, discontent, and dissidence; the shadow of a widely unpopular Shah seemed to loom over the most engaged and daring of his realm’s artists.

To conjure the Qajars’ world, the former production designer made the inspired decision to set the film’s story in a mansion which is almost a character itself, one of the film’s most important. Sand-colored, with high columns, doors, and windows decorated with bright stained glass, this archetypal Persian pile is not only where the drama occurs; it’s also, in a sense, what it’s about—since the family inside is in a state of rapid collapse, the house represents both an ungraspable vision of stability as well as the wealth that all crave.

Significantly, that family is without a paterfamilias when the tale begins. The person ostensibly in charge is a tall, dark-haired paraplegic, Lady Aghdas (a stunning performance by Fakhri Khorvash), who spends much of the drama in a large, very mobile wooden wheelchair. Aside from a sympathetic maid servant (the debut film performance of Shohreh Aghdashloo, who later starred in Kiarostami’s “The Report” and won an Oscar nomination for “House of Sand and Fog”), the Lady is encircled by several human vultures due to the large fortune she has recently inherited from her mother. Chief among these predators is the imposing Hadji Amoo (Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz, the star of Kiarostami’s “Through the Olive Trees”), the Lady’s stepfather, who must contend with other male interlopers.

The world “Chess of the Wind” describes is a hierarchy, typical of sclerotic monarchies, as stratified as a layer cake. At the top are the formality-encased aristocrats, Lady Aghdas’ circle, including a group of ladies who look like wide-eyed exotic birds perched on a branch at a zoo. Beneath them are people—mainly men—trying to boost their social status by any means necessary; they are the desperate, driven, thoughtlessly amoral prototypes of many middle-class climbers to come. At the bottom of the scale are servants, musicians, and laborers. Repeatedly throughout the film we see a group of washerwomen laundering clothes in a fountain in front of the mansion and commenting, Greek chorus-style, on the lives in their world; they seem as unhappy as their nominal betters, only for different reasons.

These scenes of the washerwomen are symmetrical compositions, filmed in static unbroken takes from a middle distance, with the mansion’s façade in the background. When we’re inside the mansion a similar visual strategy is employed. Aslani’s camera often gazes straight-on at the mansion’s capacious entrance hall with its dual staircases. But however indebted these recurrent symmetrical compositions may be to traditional Persian painting, they also serve an ingenious purpose cinematic purpose since they offset and balance the elegant camera movements that evoke Alsani’s admitted admiration for Max Ophüls.

Visually, the film is a sumptuous feast from first frame till last. Inspired by Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon,” Houshang Baharlou’s exquisitely nuanced color cinematography renders the luxurious interiors of the mansion’s upper floors solely by candlelight or natural light; here, the hues of polished woods, tan walls and expensive fabrics dominate. No less significant in the drama, the house’s basement, the lair of crimes and secrets, is painted in hellish reds, purples and blacks. In all of these settings, Alsani uses the device—suggesting a debt to Bresson—of focusing closely on various objects like guns, pearls, or glass jars as they are handled by the characters. The technique, which seems to imbue the inanimate with its own spiritual potency, stresses the materiality of the forces that drive this family tragedy.

Although the twists and turns of the film’s story sometimes seem opaque—though repeated viewings bring out the drama’s complexity and richness—one writer aptly noted that “Chess of the Wind” is image-driven rather than plot-driven. And the expressiveness of the film’s visual elements extends to its aural dimension. While the sound design brings a kind of materiality to the breaking of glass, the cawing of crows, and the ticking of clocks, the inventive score by noted composer Sheyda Gharachedaghi embeds hints of traditional Persian music within a startlingly modernistic sonic framework.

“Chess of the Wind,” which meditates on a society where traditional spiritual and social values are being displaced by a corrosive materialism, emerged from a remarkable decade of moviemaking, 1969-79, known as the Iranian New Wave (a term sometimes erroneously used to refer to more recent Iranian cinema). As Aslani’s debts to Luchino Visconti and other Western filmmakers indicate, Iranian auteurs of that era were very aware of the most sophisticated currents in world cinema, even as they strove to develop their own individual and distinctively Persian vernaculars. Despite the brilliance of their work, they are still too little known outside Iran. Perhaps the surprise appearance of “Chess of the Wind” can lead to the rediscovery of a whole era of little-known masterpieces.

Now playing in select theaters.