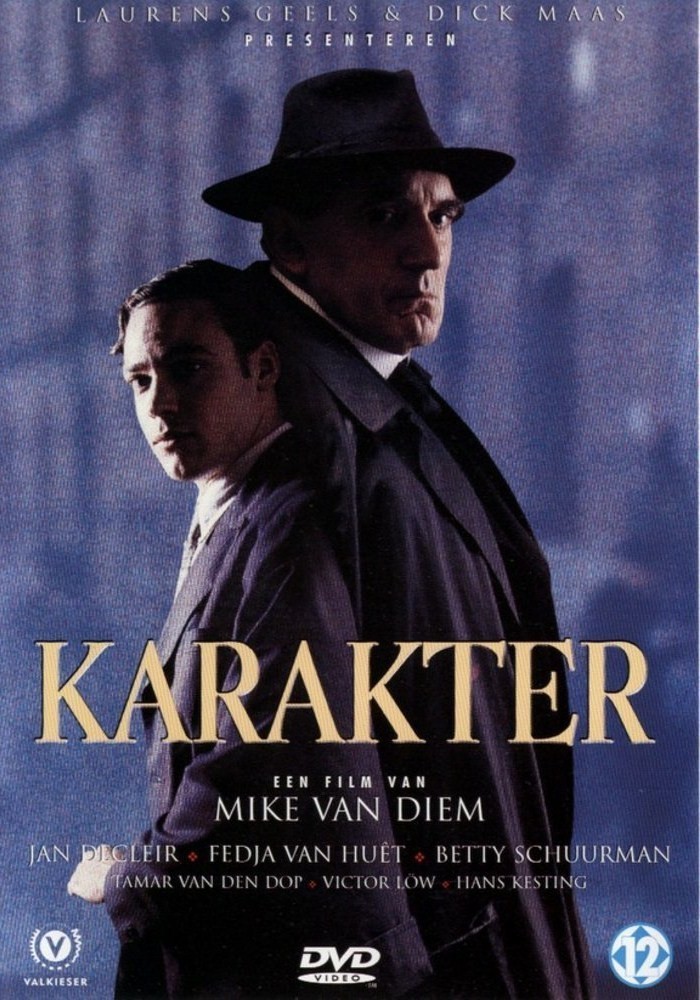

“Character” oozes with feelings of spite and revenge that grow up between a father and the son he had out of wedlock. It is dark, bitter and fascinating, as all family feuds are–about hatred so deep that it can only be ended with a knife.

The Dutch winner of this year’s Academy Award as best foreign film, it involves the character of Dreverhaven (Jan Decleir), a lone and stony bailiff who exacts stern measures on the poor. One day, and one day only, he enters the room of his housekeeper, Joba (Betty Shuurman). That visit leads to a pregnancy. The man doesn’t send his housekeeper into disgrace and abandonment, as we might expect; she freely chooses such a state, preferring it to the prospect of becoming Dreverhaven’s wife. “When is our wedding?” the stern man demands of her, from time to time, but she does not answer.

The boy is named Katadreuffe (Fedja van Huet). In school he is taunted as a bastard, and his mother is shouted at in the streets. He grows up with a deep hatred for his father. We learn all of this in flashbacks; the film opens with a confrontation between father and son, and with reasons to suspect that the boy is guilty of his father’s murder.

The film is based on a 1938 novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk. It evokes some of the darker episodes of Dickens and also, in its focus on the grind of poverty and illegitimacy, reflects the twisted stories of family secrets by that grim Victorian, George Gissing. It is essentially the story of a young man growing up and making good, by pluck and intelligence, but all of his success comes out of the desire to spite his father.

“Today I have been made a lawyer. You no longer exist for me! You have worked against me all my life,” he tells his father in the opening scene. “Or for you,” the father replies. For reasons concealed in his own past, he believes that to spare the rod is to spoil the child, and indeed calls in a loan just three days before the son’s final examinations, apparently hoping to cause him to fail. “Why don’t you leave our boy in peace?” Joba asks Dreverhaven in one of their rare meetings. “I’ll strangle him for nine-tenths, and the last tenth will make him strong,” the old man replies.

The film is set in Rotterdam, in sets and streets suggesting its gloomy turn-of-the-century shadows; I was reminded of “M” and other German Expressionist films in which the architecture sneers at the characters. The boy finds work in a law firm, rises to the post of office manager and even falls in love, with Lorna Te George (Tamar van den Dop). She perhaps likes him, too, but he is so mired in self-abasement that he cannot declare his love, and he bitterly looks on as she keeps company with another man from the office. When he encounters her in a park some years later, he tells her, “I shall never marry anyone else. I have never forgotten you.” For a man like him, masochistic denial is preferable to happiness.

The film is filled with sharply seen characters, including Katadreuffe’s friend, an odd-looking man with an overshot lower jaw, who tries to feed him common sense. There are scenes of truly Dickensian detail, as when the father evicts a family from quarters where the rent has not been paid–going so far as to carry their dying mother into the streets himself. (He says she’s faking it; he has a good eye.) The opening scenes, which seem to show a murder, provide the frame, as the young man is cross-examined by the police. The closing scenes provide all the answers, in a way, although there is a lot more about old Dreverhaven we would like to know, including how any shreds of goodness and decency can survive in the harsh ground of his soul.