The portrayal of extreme poverty in cinema presents a minefield of double-edged challenges around ethics. How can filmmakers attain and maintain a respectfully realistic, emotional tone without indulging in miserablism or condescending to their subjects less fortunate than they? Lebanese filmmaker Nadine Labaki (“Caramel,” “Where Do We Go Now?”) successfully walks that tightrope with her soberly told tale in “Capernaum,” co-written by Labaki, Jihad Hojeily and Michelle Keserwany.

In “Capernaum,” the heartache of the underprivileged is on such interminable display that you feel the physical hurt in your bones. But the manner in which the filmmaker renders these pains somehow doesn’t feel exploitative or gratuitous—there is a nuanced matter-of-factness even in Labaki’s empathy that prevents it to ever become pity. If anything, the co-writer/director seems to know and care about the exact kind of kid she follows in “Capernaum,” a fighter who has no option but to remain independent, resourceful and tireless at the end of each exhausting day the sun sets on, with no promise of a brighter tomorrow.

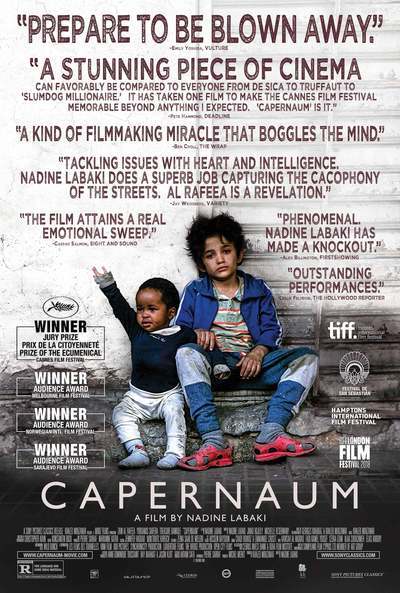

The miracle child in question here is Zain, played by the first-time actor Zain Al Rafeea with shocking conviction and level of emotional maturity. An unregistered twelve-year-old living in the deprived slums of Lebanon with his uneducated parents and crowded group of brothers and sisters, Zain is both a competent problem-solver and a perceptive observer. While these grown-up traits don’t necessarily sound tragic, they are heartbreaking assets to survey in action, as they get shaped against unique hardships no kid should ever have to experience. But the scrappy and intelligent Zain, with an old man’s toughened face and gestures sheltering his young eyes and exterior, is so buried within setbacks beyond his years that he doesn’t even recognize for a while that the innocence of childhood is something valuable he should be afforded.

We come to understand just how capable and sharp this unique boy is early on, when he instinctively grasps that his beloved sister, a pre-teen who just gets her period, would be sold to a suitor in exchange for some chickens. So he helps her sister clean up, steals sanitary pads for her from their local grocer and teaches her how to hide the traces of her blooming body. Despite all his efforts, he unfortunately loses his sister. So Zain runs away from home and one day, faces his desperate parents in court—a plotline that gets used as a structuring device while a part of the story gets told in flashbacks.

The lengthy speeches and on-the-nose explanations in courtroom scenes play didactically, going against the more honest “show, don’t tell” feature of Labaki’s film. They also interrupt the expressive narrative slightly; I found myself wondering why the filmmaker didn’t favor a chronological telling of the story and just resolve the final act into the court sequence. That hindrance aside, “Capernaum” is a relentless powerhouse when Labaki follows the misadventures of Zain as he finds a temporary safe haven under the protective wings of Rahil (Yordanos Shiferaw), an Ethiopian refugee who illegally works at a fair and mothers the impossibly sweet toddler Yonas (Boluwatife Treasure Bankole). Working on his exit plan out of the country while looking after baby Yonas after Rahil disappears (these are the film’s most soul-crushing scenes), Zain eventually falls back into the claws of his former clan.

There is an undeniable neorealist quality to Labaki’s work, bringing to mind not only the first half of Garth Davis’ “Lion,” but also the likes of Vittorio De Sica’s “Shoeshine” and Sean Baker’s “The Florida Project” (even though it falls short of the artistic command of these titles). Labaki builds the dead-end life Zain dwells in with watchfully measured details: every dried tear, every piece of hand-me-down clothing, all the mud and dust underscore the daily harshness of a world where babies wear chains (not only metaphorically) so that they can’t get themselves into danger or trouble while unattended. And thankfully, the filmmaker affirms to have no interest in misery porn by the end. In a final scene that will put a lump in your throat, she rewards Zain for his good heart, loyalty and unparalleled street-smart inventiveness. She also allows us to see this extraordinary survivor become a kid again. Or in all likelihood, for the very first time.