“Camp X-Ray” has cinematic and moral intelligence. This debut feature by writer-director Peter Sattler about a female soldier stationed at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, is a quiet, patient drama that focuses on a handful of characters and plays out in a few key locations: a cell, a hallway, a prison yard, some offices. It articulates its observations and emotions through shots and cuts, and actors’ reactions. It’s also about culture clashes, patriotism, idealism, duty, and what it means to be a woman in a job defined by primordial ideas of manhood. It is not a perfect movie—a couple of developments feel shoehorned in, and the final leg squanders the goodwill built up in the preceding 90 minutes—but it’s ambitious, and it has soul. It’s one of the better mainstream American film portraits of what happened to America’s psyche after 9/11: the moral numbness that set in right away, and never entirely lifted.

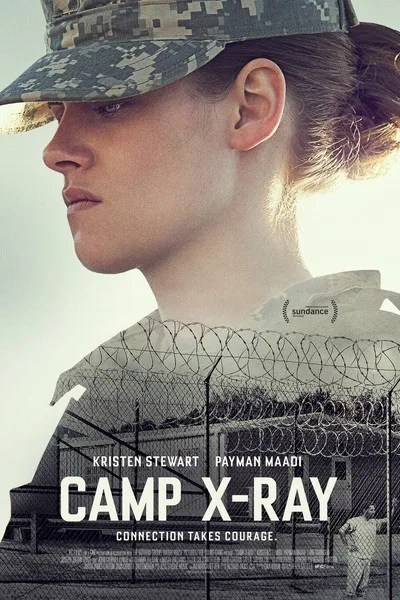

“Twilight” star Kristen Stewart carries the film on her slender shoulders. She plays the heroine, PFC Amy Cole, a young woman from a Florida town who enlisted in the Army to learn and grow, but now finds herself at Guantanamo—also as Gitmo, or Camp X-Ray—watching over prisoners. Sorry: detainees. It’s important to use that word instead of “prisoners” because, as Amy explains to a fellow soldier, “Prisoners are subject to the Geneva Conventions. Detainees are not.”

Amy’s trainer, CPL Randy Randsell (Lane Garrison), tells her right off the bat that it’s not a good idea to see the detainees as autonomous human beings, because that will get in the way of the job. He discourages her partly by playing on her insecurity as one of a handful of women at Camp X-Ray, a camp staffed mostly by burly male soldiers guarding cell blocks full of fundamentalist Muslims who don’t like being overseen by Americans generally, American women in particular.

Amy disregards Randy’s instructions and lets a stridently eloquent, English-speaking inmate named Amir Ali (Peyman Moaadi of “A Separation”) engage her in conversation as she rolls a book cart up and down the cell block hallway. The relationship between Amy, a strong-silent type, and Ali, a chatterbox provocateur, has a ‘70s-movie feel. The filmmaker lets Stewart act Steve McQueen-style, mostly with her eyes, body and hands. Moaadi jabbers and squirms and wheedles like a Middle Eastern cousin of Dustin Hoffman. Their first talk is faintly Kafka-esque: he’s read the first six Harry Potter books and has been begging for the seventh volume for two years. Amy can’t and won’t help him, offering him a two-week-old newspaper plus whatever else is on the cart. Their conversations about reading material do such a subtle job of exploring the film’s themes (they talk about Willa Cather’s “My Antonia,” a book built around a female pioneer, as well as Harry Potter) that it’s a huge letdown when the films pays these conversations off in a boringly conventional way.

Far better are the journalistic details: the magazines and newspapers on Amy’s book cart, with women’s faces blacked out; the way inmates wrap their Korans in small white blankets, and pass the time by drawing, doing puzzles, yelling at the guards and each other, and occasionally hurling feces in protest; the way that procedure, protocol and tradition rule everything, on both sides of the cell doors.

The first half of “Camp X-Ray” concentrates on showing us what it’s like to be Amy and do Amy’s job. Sattler often photographs her in ways that either disguise her femininity or complicate our reactions to it. The first time we see her, she’s silhouetted against the sun, backlit like a Clint Eastwood gunfighter. As the story unfolds, there are many close-ups taken from behind Stewart’s shoulders as Amy walks through the camp or down a cell block corridor, or sits in a chair in the mess hall or in her apartment, thinking. Our eye naturally gravitates toward her hair, which is pulled into a tight bun. The bun is at the center of the frame during so many important scenes that it eventually seems to stand for both Amy’s tightly wound personality and her workplace predicament. She gets flack for being sexually unavailable to men, but at the same time, she’s under pressure to “man up” and not show her feelings, because that’s what girls do. (Amy only lets her hair down once in the film, before Skyping with her mom.) “Are you a soldier, or are you a female soldier?” Randy asks Amy, when she recoils from an inmate’s humiliation-as-punishment. “’Cuz I don’t have these kind of problems with soldiers.”

Stewart is great in “Camp X-Ray.” Freed of her “Twilight” obligation to enact a horror movie version of fairytale-femme situations, she seems at ease (so to speak) as a tomboy. She mines a narrow emotional range with precision. Her performance is fat-free. There are silent film-quality close-ups where you can read every fluctuation in her mood even though she’s barely moving a muscle. This is a true movie star performance. When it fails to convince, it’s only because Stewart’s acting makes the heroine seem like such a distinct, real person that when Amy talks or acts like a standard conscience-stricken movie character, we can’t accept it.

“Camp X-Ray” spirals into conventional dramatics near the end, rushing through Amy’s epiphany and Ali’s despair, and turning into the hard-edged yet sentimental buddy film you hoped it was too proud to let itself be. But it’s still worth seeing for the caliber of its acting and filmmaking. Sattler and his cinematographer, James Laxton, compose striking shots that advance the story and comment on the script’s themes without becoming ostentatiously pretty. The movie makes great use of the camp’s coldly anonymous architecture, framing guards and prisoners within rectangles and squares and converging diagonal lines, and sometimes dwarfing them in long shots that have the geometric solidity of a Piet Mondrian painting. The editing, by Geraud Brisson, juxtaposes shots in cheeky ways, as when the movie crosscuts between a Muslim call to prayer and soldiers lining up for morning inspection: the sequence is capped by a shot of the the US flag flapping in the breeze, as if to suggest that blind faith in a nation’s goodness is its own kind of state religion.