She is above all a lonely woman, because she chooses to do with her life what her society says no decent woman should do. She chooses to love who she will, and she wants to be an artist – to create sculptures out of clay, just as if she were a man. It is hard to say which of her choices is the most offensive. And when she goes mad, it is impossible to say whether the seeds of madness were there from the beginning, or whether she was driven to madness by a society that could not accept a woman who lived for herself.

Camille Claudel has until now occupied only the footnotes of late 19th century art. She was one of the mistresses of Auguste Rodin, the willful sculptor who is known to everyone, if only for “The Thinker.” She was often his model, and for a time she worked as his collaborator. She left behind many sculptures, which can be seen here or there, not much remarked, while Rodin’s work has been enshrined in the pantheon. She spent the last 30 years of her life in a madhouse.

The film “Camille Claudel” is more concerned with her personality and passions than with her art, and so it is hard to judge, from the evidence on the screen, how good a sculptor she really was.

This is not a movie about sculpture. Those who have seen her work report that some of it has a power that is almost disturbing – that there is an urgency in her figures suggesting she was not simply shaping them, but using them to bring her own emotions to life.

Certainly the pressures against an independent woman artist were sufficient in her late 19th century Paris that she would not have bothered to be a sculptor unless she absolutely had to.

The first time we see her, she is grubbing in the dirt of a Paris construction site, down there in a ditch like a burrowing animal, looking for good clay that she can use in her work. She straightens up and as she rubs the sweat from her face with a filthy hand, we see her as a very young woman with eyes that see more than this ditch she stands in: She sees, already, the figures she will mold from this clay.

She is played by Isabelle Adjani, who has been nominated for an Academy Award for her work, and one of the mysteries of this performance is how Adjani, now in her 30s, is able so convincingly to span this woman’s lifetime and seem to be the right age at all times.

She is certainly convincing in the early scenes as a young, open, determined woman who has somehow got it into her head that not only men should be sculptors.

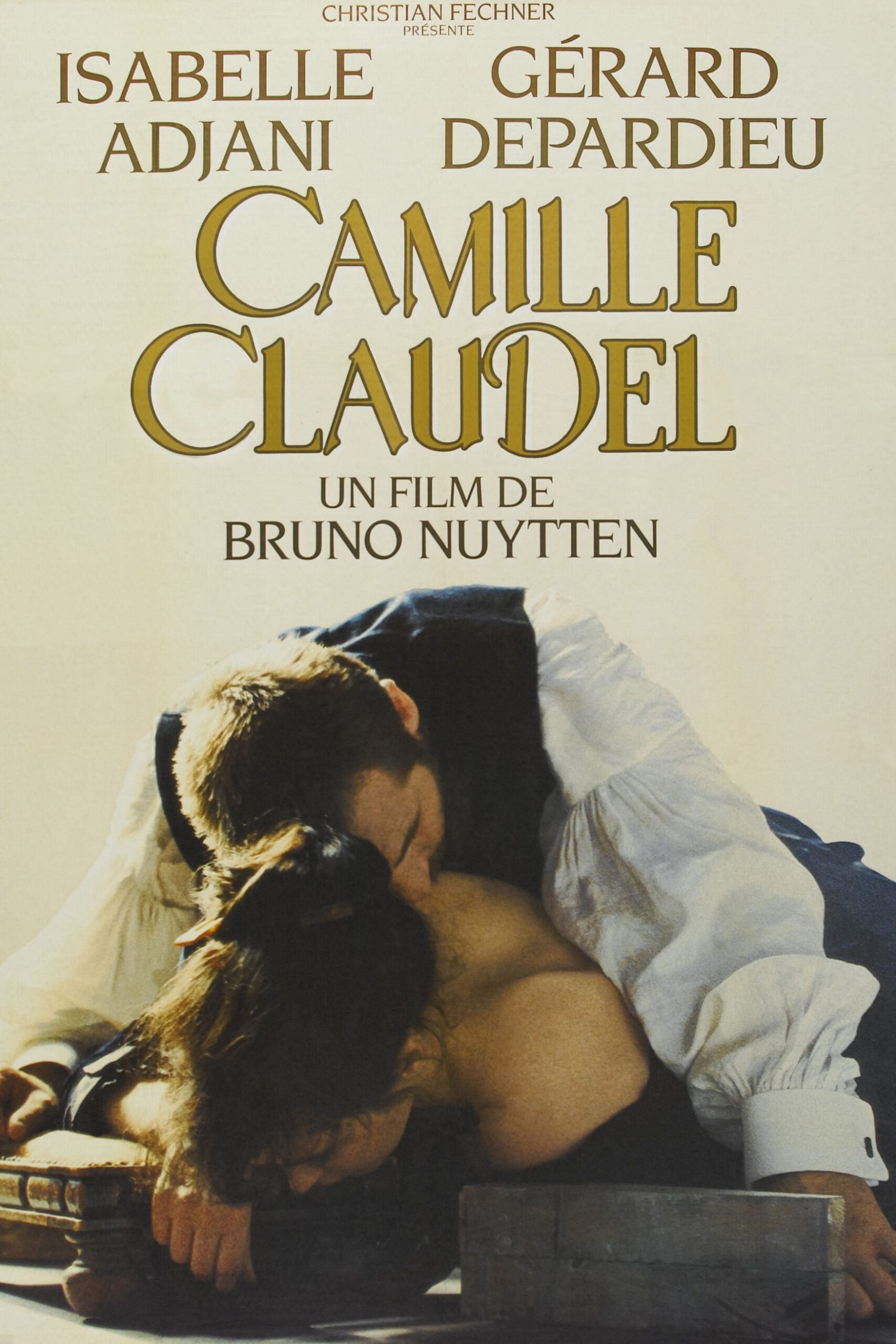

As an Academy student seeking a new teacher, she meets Auguste Rodin (Gerard Depardieu), who looms like a colossus over the art world of his time, not least because of his ability at self-promotion. Rodin was one of the inventors of the artist as celebrity, rejecting the myth of the lonely recluse in the wretched garret and consciously occupying the spotlight. At first he pays little attention to her, even though he has a reputation as a womanizer. She observes his longtime mistress, Rose Beuret (Daniele Lebrun), and wonders if they are married. She works on a piece of marble he has given her and creates a foot, a wonderful foot that he acknowledges as well-made. Then they fall into each other’s orbit, he is bewitched, they make love, she becomes pregnant, he will not leave Rose, and she begins the long descent into madness.

Rodin is simply not capable of being faithful to one woman. Nor is he much interested in a woman who dares to think of herself as his artistic rival. Such a woman can only be allowed to grow so far, to be encouraged so much, before she must be slapped back down into her place in his bed. Is this rejection what drives Camille mad, or is it the fundamental contradiction between what she is, and the time she lives in? We follow her gradual decay, as she moves into shabby lodgings and goes without food or fuel to pay for her art. This behavior concerns her parents, who begin to wonder if she has lost her senses, especially when she begins to drink and to neglect the impression she makes on people.

Adjani is possessed in this movie. It is not one of those leisurely costume dramas in which people in beautiful costumes move through elegant rooms. Her eyes always look haunted, and even in the moments of luxury and romance there is the suggestion in her body language of that feral creature down in the ditch, grubbing for clay.

She makes sculptures because she must – because the figures in her work are trapped within her, and if she does not release them she will burst.

Depardieu plays a Rodin who is genial, assured and malevolent. He will go only so far for a woman before he must pull back and he sure that his ego is served. Has there ever been another actor, in any language, who seems so unself-conciously assured in such a variety of roles? Depardieu works all the time, always well, and just within the last few years he has been not only Rodin but also the hunchback peasant of “Jean de Florette” and the love-struck car salesman of “Too Beautiful for You.” Artistic biographies are notoriously difficult to film, because what an artist does takes place within his mind, and the camera can see only the outside. Sculptors are at least a little easier to deal with than writers or musicians; instead of Balzac or Mozart furiously scribbling on a piece of paper, we can at least see the knife shaping the block of clay. But “Camille Claudel” is not really about sculpture anyway. It is about a woman who tried to place sculpture before everything, until she met a man who did the same thing.