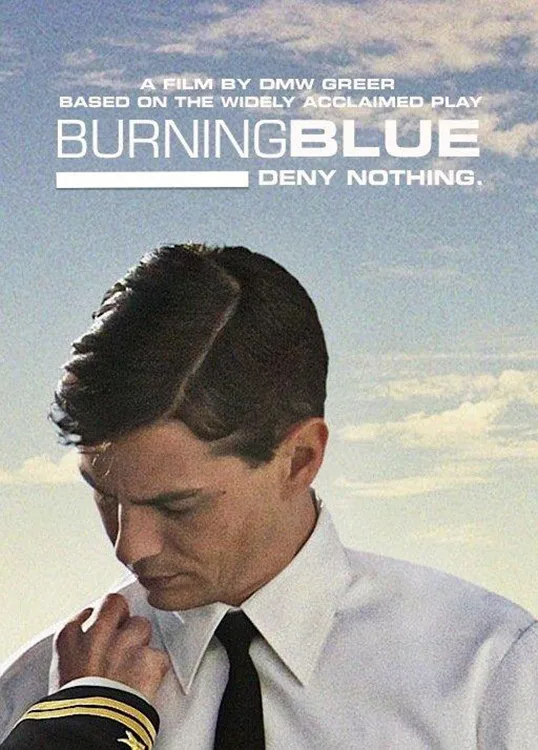

Because of “Burning Blue”’s Navy-pilots-in-love plot, “The Backlot” website referred to the film as “Brokeback Top Gun.” If only this were true. Instead, this shockingly amateurish film evokes memories of “Making Love,” the Arthur Hiller film about a married man coming to terms with his homosexuality. That film’s made-for-TV movie kid-glove treatment of this subject equates to head-shaking camp today, but is forgivable because “Making Love” was made in 1982. “Burning Blue” has no excuse to play coy in 2014, especially when its romance is supposed to play an integral part in the story.

DMW Greer’s adaptation of his 1995 play has honorable intentions. It wants to show how “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” ruined the lives of many who served in the Armed Forces. A straightforward, heartbreaking drama exists in this material. But Greer’s dialogue and plot points push far beyond the edges of melodrama. Rather than base the witch hunt on the mere speculation that a pilot may be gay, “Burning Blue” creates an investigation into members of one particular squad whose pilots keep dying on flight maneuvers. The series of events leads the Navy to think there’s “a gay cell” endangering its pilots. As absurd as that sounds, it’s actually believable that the Navy would think this. How “Burning Blue” gets here, and what it does afterward, is far more problematic.

It’s not a gay cell causing the accidents, it’s a straight pilot. Will Stephenson (Morgan Spector) selfishly wants to go into space, so he hides the fact that his vision is worse than Mr. Magoo’s. Complicit in this is Will’s BFF and co-pilot Daniel Lynch (Trent Ford), who takes blame for the non-lethal accident that opens “Burning Blue.” Since he could not see at a crucial moment, Will flew into a flock of birds, forcing he and Daniel to punch out of the cockpit.

The platonic relationship between Will and Daniel takes center stage, leaving little room for the romantic events that cause Daniel to out himself to the Navy. These events almost seem an afterthought, as NCIS already has enough “evidence” to nail Daniel and accuse Will: A naked picture of Will and his squadron in rather suggestive poses, taken while the crew was drunk in Italy. Greer is way too skittish to show this full-frontal snapshot onscreen longer than 2 seconds, so the pause button is necessary to see just how “incriminating” it is.

There’s more action in that photograph than in the affair between the engaged Daniel and the married Matthew (Rob Mayes). While spending a shore leave day together, Matthew and Daniel take a rather sweet tour of New York City, which culminates with them hooking up with two other people for a one-bed romp. Greer intercuts this poorly framed disaster of a sex scene with scenes of a shirtless Daniel and Matthew doing the funky chicken together at a gay dance club. An angry sailor, who had been punished earlier by Matthew for insubordination, sees this sweaty, shirtless boogie and becomes the star witness against Daniel.

“Burning Blue” is ambiguous about whether Matthew and Daniel sleep with each other. It is certainly not shown, and, outside of one kiss and a scene of Daniel running his fingers through Matthew’s hair, there is no physical interaction between them at all. Greer forces his actors to repeatedly stare longingly at each other from across crowded rooms, as if this were “Some Enchanted Evening.” Neither actor is up to the task of conveying this silent passion; their constant stares make them look constipated. When Matthew decides to leave his wife and endanger his career, the first question one asks is “Why?”

Even worse, the NCIS agent tormenting Daniel and his crew is the Javert of homophobia. He’s relentless, showing up comically in places one would not expect, as if he can telegraph where people will be. Wielding his camera like a weapon, he takes photo after photo of innocent activity to build his case. His body language screams “VILLAIN!” and his dialogue is a wellspring of purple prose. His appearances should be accompanied by a horror movie stinger. The interrogations by him and an African-American special agent are so poorly staged they have little suspense. The use of the latter character is particularly nauseating; after persecuting Daniel in scene after scene, he tells him “you’ll feel better if you accept yourself for what you are. It took me a long time to accept that I was Black.”

If you see “Burning Blue,” ask yourself what its last scene is supposed to mean. It’s a reunion between Daniel and the extremely homophobic Will. Will calls Daniel the F-word, but Daniel still wants a reconciliation between the two. Considering what Will has done to Matthew, this development is a jaw-dropper. Is this supposed to be some kind of victory for LGBT people?

Maybe this material worked in 1995; Wikipedia mentions that it opened to acclaim and awards. Today, it has an air of the old tragic mulatto movies that permeated the 1950s. Again, the intentions are noble; it’s the execution that will stick in your craw. Audiences deserve better depictions of the tragic aftermath of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” than this meek, dated Afterschool Special.