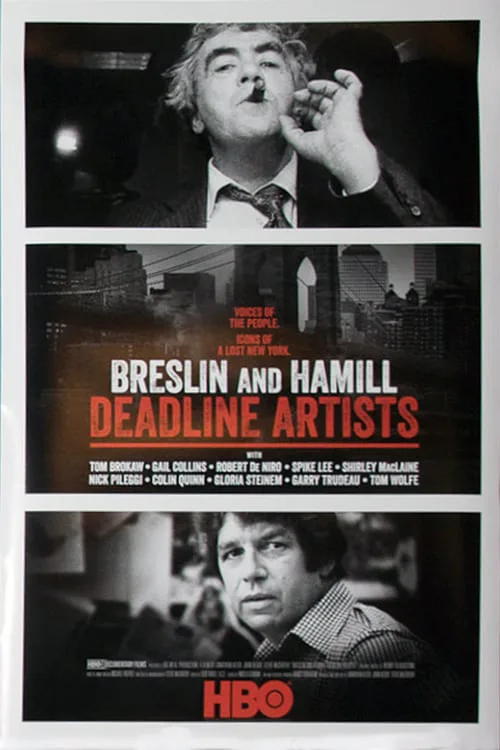

One of the numerous strengths of the HBO documentary “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists” is how its directors Jonathan Alter, John Block and Steve McCarthy propose that a former news cycle is repeating itself now. In one clip, disgraced vice president Spiro Agnew launches an attack on “the evil liberal media” and how it is poisoning and distorting the facts of the Nixon presidency, and one almost expects him to yell “fake news!” In another, someone casually mentions the impending demise of the printed newspaper before adding that this was back in 1972. And in a third, a much younger incarnation of a certain politician is shown spouting the same vein of divisive racial hatred as he is right now. The film slyly implies that we’re trapped in a news-based remake and makes us long for the writers who covered it first.

Those writers, Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill, should be familiar to anyone born and bred in the New York City area within the last six decades. They were larger-than-life newspapermen whose columns changed the way news stories were covered. Their words leapt off the page, spoken fluently in the dialects of their well-known personalities. Theirs was the era of the hard-drinking, deadline-making, truth-seeking, typewriter pounding (and oddly enough, always male) grouchy beat writers romanticized in entertainments like “The Front Page” and “All the President’s Men.” Despite a celebrity status that eluded most of their journalistic brethren, Hamill and Breslin’s prose remained in the trenches with the common man, always seeking empathy for the downtrodden while challenging the powers that be.

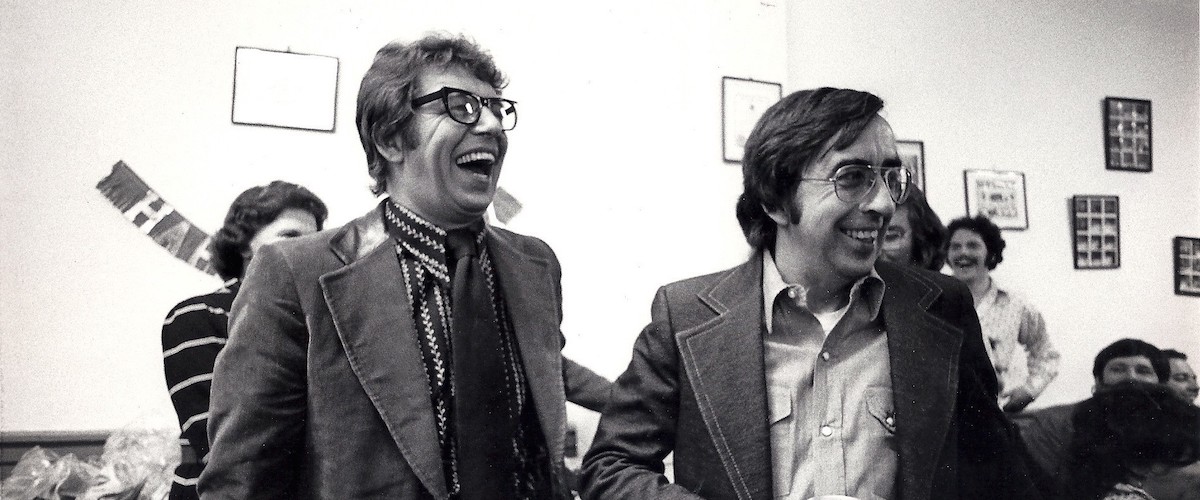

The two native New Yorkers appear onscreen in interview footage shot in 2015. They have an easy rapport, riffing off one another while exchanging stories of their heydays. In the timeline, Breslin’s column appeared first, the trendsetter sent to liven up things at “New York’s most boring newspaper,” the New York Herald Tribune. In 1962, Breslin’s style became so popular that other papers wanted their own version. Enter Pete Hamill, who was nothing like Breslin prose-wise, but whose heart and compassion bled as deeply into the newspaper ink as Breslin’s did. Hamill had been a reporter at the New York Post before manning the type of column he would write for decades.

In 1976, the duo were both under the auspices of “New York’s Hometown Paper,” the Daily News, which is where and when I discovered them. Before that, Breslin and Hamill crossed paths many times while working their respective beats, including on the day Senator Robert Kennedy was shot. Both men helped subdue Sirhan Sirhan. “I sat on his feet,” Breslin tells us. “You rode in the ambulance with him, didn’t you?” Hamill asks. Breslin says yes, reminding us that Kennedy was still alive en route to the hospital. “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists” also reveals that it was Hamill who convinced RFK to consider running, an action for which the current day Hamill expresses some regret. “I never became friends with another politician after that,” he tells Breslin.

The Kennedys haunt the documentary several times. Breslin wrote one of his most well-known columns a few days after November 22, 1963, a hauntingly beautiful interview with the African-American man who dug President Kennedy’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery. Snippets from that article (and many others by both men) appear on screen, with the late Breslin’s words (he died in 2017) being read by writer Michael Rispoli and Hamill reciting his own. Years later, Hamill would date Jacqueline Onassis, a story Breslin would use to very amusing effect in one of his own columns.

The talking heads in “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists” are a fascinating mix of relatives, actors, directors, former journalists turned best-selling novelists and other writers who either worked with the film’s subjects or were competitors. Spike Lee turns up to talk about Breslin’s work, but for some reason he’s absent when the subject turns to Breslin’s dealings with the Son of Sam, David Berkowitz, the subject of Lee’s film “Summer of Sam.” Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese supply color commentary as only they can. Earl Caldwell talks about the newsroom atmosphere at the tabloids, and how Breslin didn’t mind going to the rowdiest Black hangouts with him to get stories. And there are reminiscences by family members, many with language as blue as you’d find in a reporter’s local bar.

Some prominent women are also present, with informative quotes from journalist Gail Collins and Cibella Borges, a police officer whose story was prominently told by Breslin across numerous columns. Hamill and Breslin also speak of the mysterious Anne Marie, the woman who sat between the two in the newsroom. Anne Marie had a very particular set of investigative skills that I wouldn’t dare spoil here.

Though their names are in the title, the real stars of “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists” are the words they wrote. Several times, I was moved by the descriptions chosen by the filmmakers. It is here where I must disclose my own bias: I grew up in Jersey City, New Jersey reading their columns, and so many of the defining events of my lifetime (Nixon’s resignation, 9/11, the Central Park Five) were filtered through this prism. So I was most appreciative of this film’s construction, its focus on words and its warts and all treatment of its subjects.

At the end, we’re left with the burning question of whether history’s repeat will have journalists to cover it who are as good as those who witnessed it the first time. Strangely enough, this film has hope that it will. I remain pessimistic and sad, but so what? As Jimmy Breslin once said, we weren’t put on this Earth to be happy.