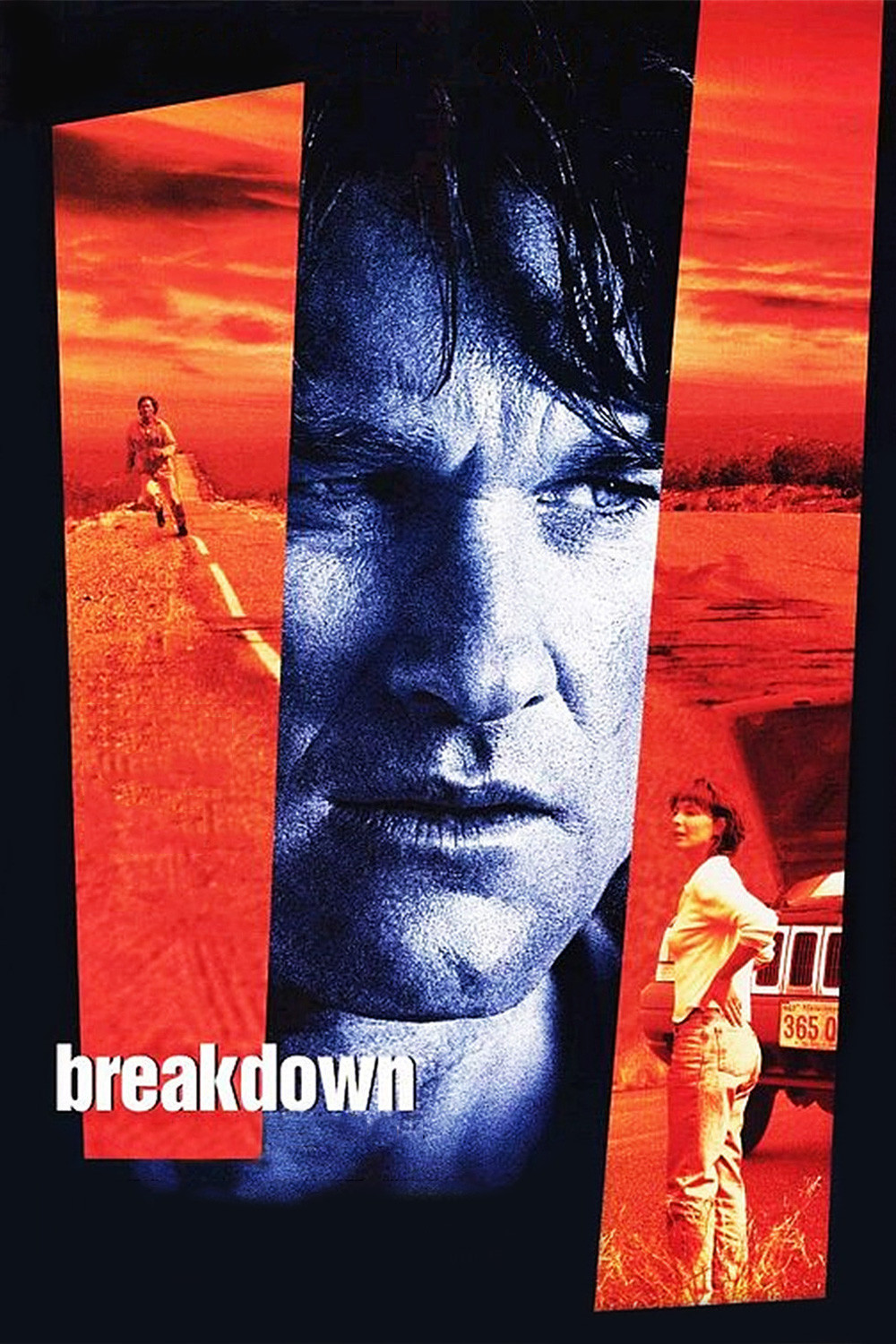

“Breakdown” is taut, skillful and surgically effective, the story of a man who finds himself trapped in a surrealistic nightmare. The story’s setup is more entertaining than the payoff; as Hitchcock observed, suspense plays better than action. But the film delivers–right up until a final moment I’ll get to later.

Kurt Russell and Kathleen Quinlan star as a Massachusetts couple driving to California through the deserts of the Southwest. They’ve made two mistakes, as a character later helpfully explains: driving a brand-new red Jeep and having out-of-state plates. In the middle of nowhere, the car breaks down, or so they think, and they are left at the mercy of the locals.

The locals do not come well-advertised. Early in the film, the Jeep nearly sideswipes a dusty black pickup driven by a stringy-haired goon (M.C. Gainey) who looks like he belongs back home in the swamps of “Deliverance“. He later accosts them at a gas station, and Russell floors the Jeep in an attempt to put highway space between them. That may be a mistake during the new car’s break-in period; it has an engine meltdown in the desert, and they seem to be at the mercy of the goon until a helpful semi driver (J.T. Walsh) happens along.

Now I will move carefully to conserve plot details. Walsh offers them a ride to a nearby diner, Russell chooses to stay with his car, and Quinlan accepts the offer so she can phone a road service. But when Russell later arrives at the diner, no one there has seen his wife. And when he stops the truck driver for a highway showdown with a deputy sheriff on hand, Walsh convincingly argues he has never seen the woman. Russell narrowly avoids being arrested, and is left standing beside his car in the middle of nowhere, baffled and angered by the disappearance of his wife.

The situation at this point resembles the opening dilemma of “The Vanishing” (1988), a brilliant Dutch-French thriller (accept no substitutes; the 1993 U.S. remake is a pale shadow). In that one, a couple paused at a highway rest stop, the woman walked inside and was never seen again. There is a moment here when Russell stares at a wall of missing persons posters in the local sheriff’s office, and realizes how common it is for people to disappear into thin air. (The sheriff cheerfully quotes discouraging statistics.) What happened to his wife? I will tell no more than necessary, but stop reading now if you want total suspense. If “Breakdown” had the courage of “The Vanishing,” which was a chillingly nihilistic film, we would never find out–or, we would discover things we would rather not have known. But this is an American thriller, and so it is preordained that Russell will find himself on a desperate solo struggle to find his wife and save her. (If you can’t guess that, the previews provide a large hint with a shot of him hanging onto a speeding truck’s undercarriage.) In the course of his quest, there are two scenes that don’t work as well as they should. One is a scene in a small-town bank, which shows Russell behaving so awkwardly that opportunities for suspense are lost; the director, Jonathan Mostow, seems to have realized that and cuts away from the bank abruptly without concluding the sequence.

Another is a scene where Russell, being pursued by villains, unwisely drives his nice new Jeep down an embankment and into a river. In the Jeep commercials, it would power across to the other shore, but in the movie, it floats downstream, allowing him to discover, in the vastness of the landscape, a single tiny doughnut wrapper that provides an unnecessary clue.

Those scenes raise questions. The others do not. For most of its length “Breakdown” functions so efficiently that we put logic on hold and go with the action. Russell makes a convincing, dogged, weary Everyman, and the J.T. Walsh character is given some shades that are interesting (including his relationship with his wife and son).

I’m recommending “Breakdown,” but I have a problem with the closing scene I mentioned above. It involves a situation in which a villain is disabled and powerless–yet a coup de grace is administered. There is (or was) a tradition in Hollywood thrillers that the heroes in movies like this kill only in self-defense. By ending as it does, “Breakdown” disdains such moral boundaries.

I noticed, interestingly, that no one in the audience cheered when that final death took place. I felt a kind of collective wince. Maybe that indicates we still have an underlying decency that rejects the eye-for-an-eye values of this film. “Breakdown” is a fine thriller, and its ending is unworthy of it.