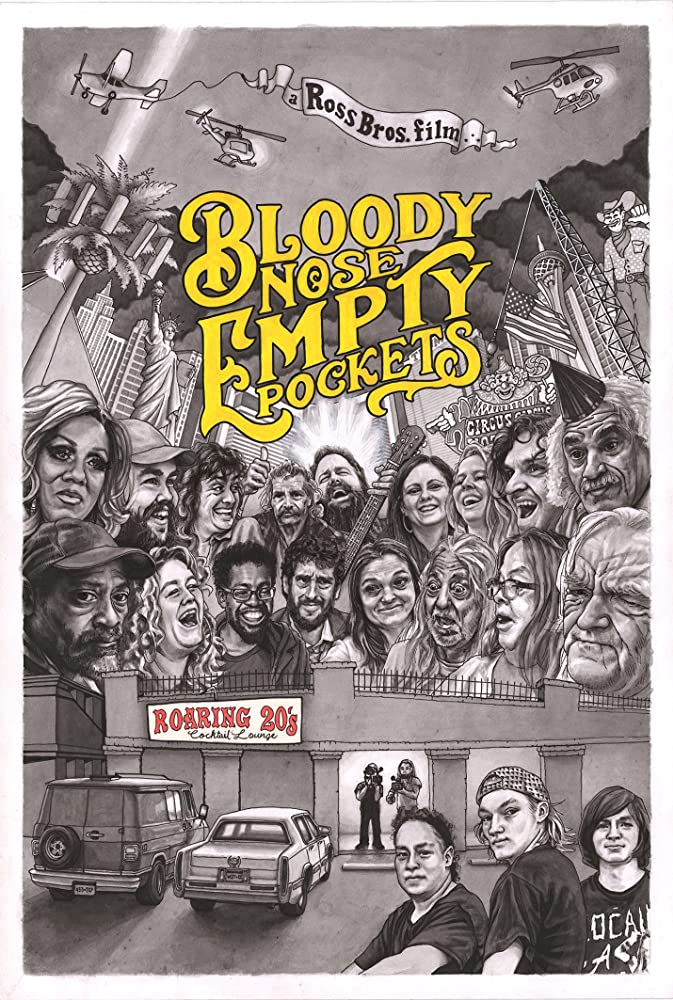

Bursting with humanity, grounded in humility, and in love with the poetry of faces, “Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets” is a classic indie film that will irritate or mystify some viewers while inspiring evangelical fervor in others. The rating at the top of this review tells you where this writer stands. Set on closing day at The Roaring 20s, a Las Vegas dive bar with basement rec room decor, this gem from co-directors Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross is a reminder that good films can be made cheaply as long as they supply the audience with remarkable moments. This one consists of nothing else.

An old intellectual boozehound with a craggy face and an ivory mane entreats a glamorous Black trans woman who’s stepping out for a while to make sure to come back so he can sing a duet with her. “Don’t threaten me!” she peals, and they both laugh. A Black Vietnam vet sits on a corner stool, lost in thought as conversation swirls around him; the camera zooms in until it’s close enough to see the trauma behind his eyes. The bartender, a bear of a man with a ZZ Top beard and shoulders wide enough for cats to sit on, takes a call on the house phone from a patron in the back who wants to know if he’s ever going to get that beer he ordered. Later, that same prank phone caller—a skinny, older white guy with granny glasses, a long grey ponytail, and semicolon posture—dances with the vet to a Michael Jackson song. Another caller starts his conversation with the bartender by asking how he’s doing (something nobody thinks to do) then asks he could please find Ira and tell him to stop drinking and go to work.

I could keep adding to this list, but if I did, you’d be here longer than the running time of Eugene O’Neill’s four-hour barroom epic The Iceman Cometh, a play that the Rosses have cited as a primary influence. There are bits and pieces of other works in here, too, notably “Trees Lounge“—the reigning US champion of dive-bar cinema, populated by Queens eccentrics and more than a few hardcore alcoholics—and “Big Night,” which builds toward a closing night party at a struggling restaurant, and likewise carves out space to note fleeting epiphanies, such as a woman slouched over a table after a night of magnificent feasting who says, through tears, that her mother was a terrible cook.

The style of “Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets” mingles documentary cinema and improvisational drama with such ease that, after starting the film without reading about it first, I decided to resist the urge to find out which it was, so thoroughly convincing were the characters, the intricate soundtrack (which catches multiple conversations simultaneously, some occurring offscreen) and the fly-on-the-wall cinematography (also by the Rosses). It’s a gift to be able to birth a moment into being by finding the right camera subjects and letting them be themselves. Everyone involved with this production has the gift.

Still, I guess I have to take a sidebar here and tell you about something that didn’t bother me in the slightest, but that seems to have bothered a number of my fellow critics: the Rosses started out making documentaries and call this film a documentary as well, but it’s the result of auditioning barflies around the country, choosing the ones they found most fascinating, then spending two 18-hour days in a New Orleans bar with them, feeding them situations and topics, watching them make drama from it, then cutting the results together with exterior shots of Las Vegas (shot through eerie filters that evoke the irradiated Vegas of “Blade Runner 2049.”) Some of the performers have prior acting experience. Most don’t. The movie doesn’t identify which are which, and in most cases it’s hard to tell. I’ve read reviews of “Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets” that find something unsettling in this blurring of fiction and fact, and question whether it was deceptive of the directors to label the result as nonfiction.

I don’t think the question matters much when you think about how many different international cinemas throughout the decades—particularly Italy after World War II, and Iran in the late 20th century—made art by blending reality and fiction. These films wove their narratives around nonprofessional performers (and sometimes a few professionals skilled enough to fake amateurism) playing a version of themselves. But if it did matter, I’d point to the many shots in the movie which plainly acknowledge that the only “reality” onscreen is the record of a filmmaking experiment.

One scene starts with a closeup of a barfly looking into the camera before reminding himself that he wasn’t supposed to do that. A handheld lateral tracking shot follows the bartender as he walks behind the bar, the camera operator is not only visible in the wide mirror behind him, but stays in the shot so long (in a variety of mirrored surfaces; no matter how many times the poor guy repositions, you can still see him) that it’s impossible not to fixate on it. If the Rosses—who have been transparent about their production methods in interviews—were trying to fool anyone, they would have deleted those shots, and others like it. “Everything’s a fucking documentary,” Bill Ross told The Guardian. “Some people perform plays in front of the camera. We’re going about it slightly differently.”

Whether or not this is, strictly speaking, a “documentary,” it is certainly a movie that prizes documentary values: a record of a spontaneous occurrence. The framing is rough-and-tumble. You can tell it was a struggle to capture some of the wilder spontaneous moments without interrupting the performers’ flow—and that, faced with the choice of destroying a scene’s momentum and staying put and hoping for the best, they stayed put. The result finds beauty in simplicity. If you counted how many cuts there are in the film, you might not break three digits. But there are no ostentatious, Hollywood-slick shots—just instance after instance of the filmmakers finding the most interesting person in the room (who might or might not be the one doing the talking) and staying on them for a long time, to see what happens.

The vet quiets everyone else down and says he wants to tell a joke that’s really more of an aphorism about human nature, and a deep one at that, but his audience else gets hung up on his repeated mispronunciation of the word “few” (maybe result of dental issues or a speech impediment) and won’t let it go. The camera stays on the vet the whole time, crystallizing a moment that everyone has experienced at one time or another: a sincere attempt to connect, derailed by listeners who keep fixating on some minor, meaningless element. The bartender and several patrons watch “Jeopardy!” on the corner television, failing to get a single answer right. “Fuck this game,” the bartender says, prompting gales of laughter from the customers. “What are we watching this for, to feel stupider? Like I need to feel dumber today, I already gotta deal with you clowns! Alex Trebek, you son of a bitch—you got the answers right in front of you, man!” The camera stays in a static wide shot the entire time, letting you choose which character to look at, and heightening your awareness of how much these regulars have come to depend on each each other. Friendship is an intoxicant, too.

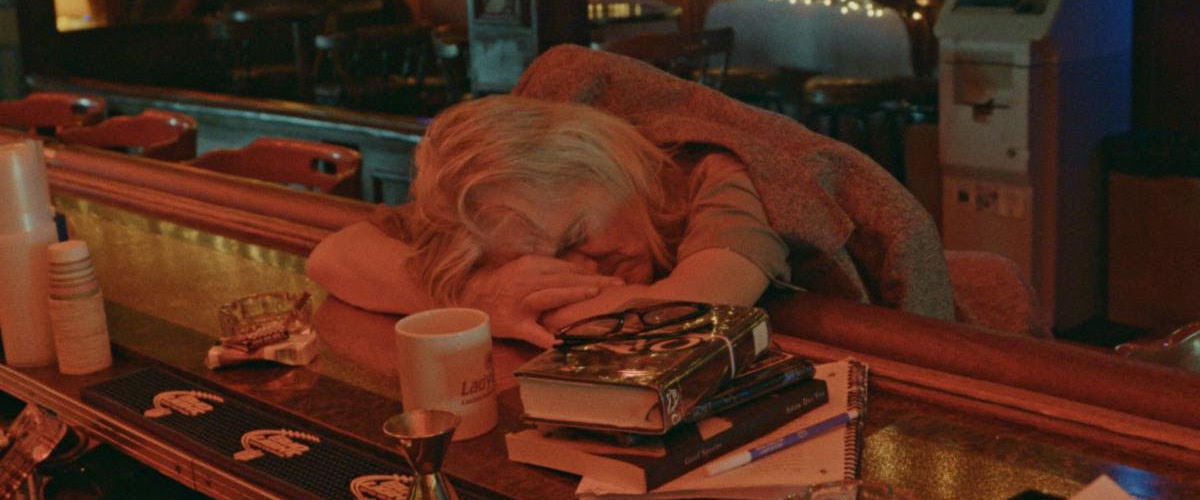

Other times, the filmmakers’ ability to concentrate—to really look and listen to their characters—cracks a moment open and releases deeper meanings. My favorite finds a drunk, drooling patron standing in the open doorway of The Roaring 20s as Michael, the intellectual barfly, urges him to go home. Most of the shot is obscured by an interior door frame and, more so, by the bartender’s back and shoulders. Michael is squeezed into a v-shaped gap in the blackness, like he’s part of a paper collage. Michael’s sometimes-not-visible face, the drunk’s disembodied voice, the bartender in the foreground, and the rectangle of merciless, blown-out sunlight backlighting the action combine, evoking primordial dread. It’s as if one being is urging another to leave the womb, or give in to death’s release, while we bear witness.

The movie keeps doing this: finding a moment—small, big, happy, horrible—and staying in it until feels like it’s time to move on. The filmmaking and performances are operating on the same wavelength. Performers and crew agreed to try something, then went to a bar and did it and filmed it. This commitment to a vision—not just a filmmaking vision, but a vision of life—gives the project a philosophical spine. The range of thoughts and emotions released by that vision is the reason the movie exists. That scene in the doorway is a metaphor for the film you’re watching, and for everything. “Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets” is about people who have come to think of their favorite watering hole as a place of refuge, and are so frightened by the certainty of losing it that they spend their final hours there pretending it’s just another day. And isn’t that what everyone does, each day of their lives? You go through one doorway and leave through another. You don’t remember what came before. You can’t know what comes after. And in between: days, hours, seconds.

As Michael points out in a monologue, most people don’t have a lot of control over what happens to them, even when they loudly insist that they do. Admitting this can be paralyzing at first. You move past it by realizing that what matters most is what happens while you go about your business in that in-between space. It’s all a series of moments. The finest ones are centered on other people. And the greatest gift one person can give another is to appreciate them.

This movie appreciates every person that passes in front of its lens. It throws spotlights on magic moments even when the people they’re happening to don’t know they’re happening. It sees people’s potential even if they’ve never capitalized on it. It sees their pain when they can’t admit or describe it. It sees their struggle when they try to hide it. It’s a documentary of compassion.

Now playing in a virtual run through at Film at Lincoln Center, with a rollout to follow