We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. #BlackLivesMatter.

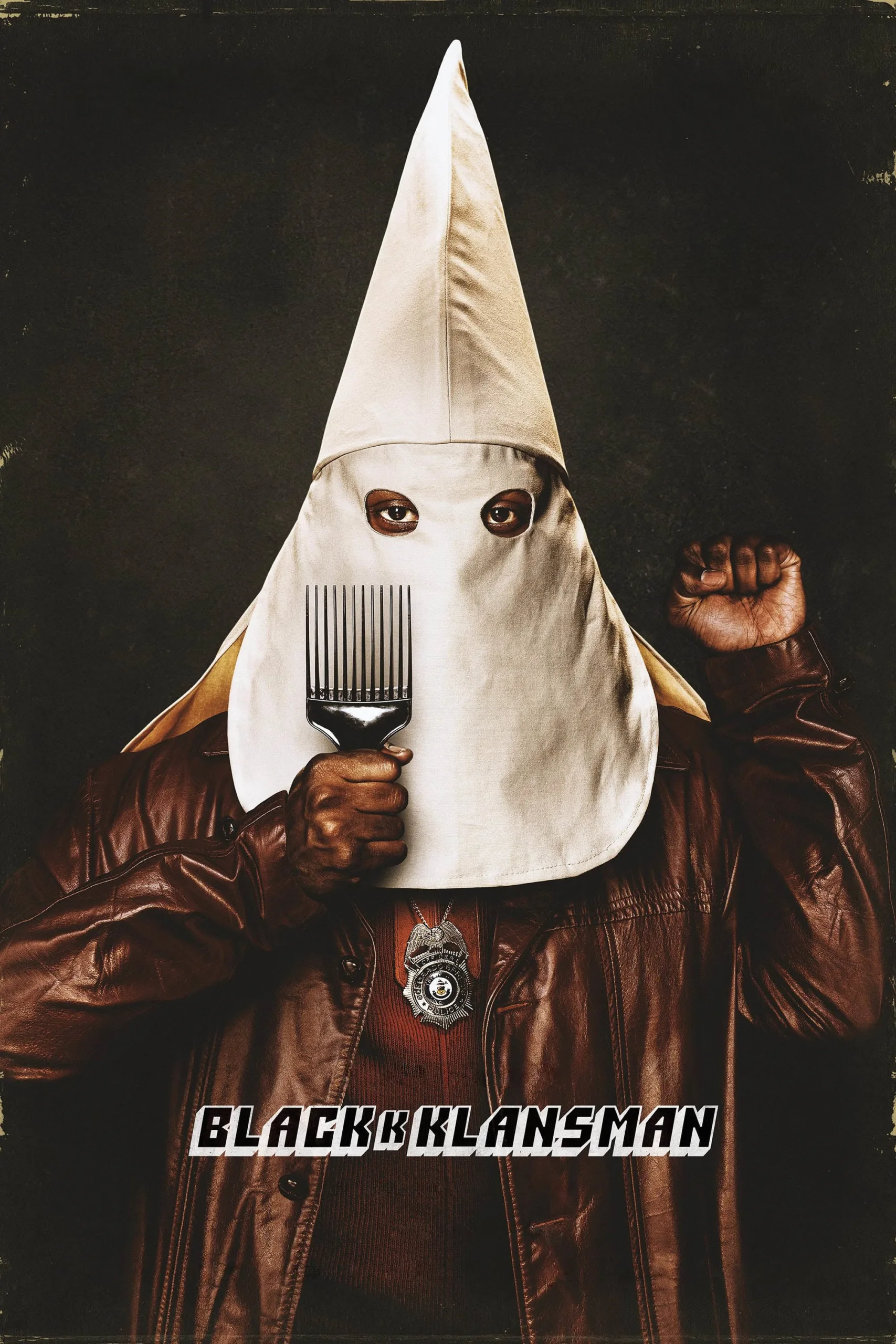

“BlacKkKlansman” presents racism as a dichotomy between the absurd and the dangerous; the film’s intentional laughs often get caught in one’s throat. Director Spike Lee and his co-screenwriters Charlie Wachtel, David Rabinowitz and Kevin Willmott adapt a tale of deception based on some “fo’ real, fo’ real sh*t” that was first covered in Ron Stallworth’s 2014 memoir. Stallworth was a Black Colorado Springs police officer who successfully infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan, going so far as to speak with David Duke on several occasions. Stallworth’s undercover police work, aided by an immeasurable assist from his White partner, Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) helped expose and quash an attack on Black activists.

This is not Lee’s first cinematic depiction of the KKK. In “Malcolm X,” he presented them riding “victoriously” into the night while a preposterously large moon hung in the sky. It’s a quick scene but its intentions are unmistakable: Lee is evoking D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” one of the most effective pieces of propaganda racism ever had, but he’s not paying it any tribute. Instead, the obvious fakery of the gorgeous, celestial backdrop behind the Klan served as a middle finger to Griffith and his film. Though the action in Lee’s scene is dramatically potent and played straight, the technique itself is parodic, as if to call bullshit on the notion that Griffith’s filmmaking prowess excused the vileness of what he depicted.

In “BlacKkKlansman,” Lee has more middle fingers to wave at Griffith’s alleged “masterpiece,” starting with the use of footage from “The Birth of a Nation” itself. We are shown it being screened at a Klan meeting, and it also figures in a pre-credits short film starring Alec Baldwin, playing the awesomely named Dr. Kennebrew Beauregard. As in “Glengarry Glen Ross,” he sinks his teeth into a ranting monologue, except rather than harping on steak knives and potential unemployment, this incarnation of Baldwin is peddling racism on a filmstrip. And he’s far from perfect at doing so; several times he stammers over his words or needs to be fed lines from an off-screen script person.

What Dr. Beauregard says is disgusting, yet it prepares us for the horrible slurs and comments we’ll hear almost non-stop for the next 135 minutes. Lee projects distracting images over Beauregard as he delivers his imperfect line readings, highlighting his incompetence to the point where you might ask yourself “who’d believe a thing this guy is selling?” But Dr. Beauregard will have plenty of buyers. They’ll forgive that he looks ridiculous because they believe, as Randy Newman once sang, that “he may be a fool, but he’s our fool.”

Next, we meet our protagonist, who is played by Denzel Washington’s lookalike son, John David Washington. Like his Pops, the younger Washington is beloved by Lee’s camera. From his first appearance, cinematographer Chayse Irvin caresses his handsomeness with a delicate touch that is curiously chaste for a Spike Lee Joint. As Ron Stallworth approaches the Colorado Springs Police Department building, the camera hangs above him as he walks into frame. With his impressive ’70s-era threads and an enviable halo of Afro-formed hair, Stallworth looks as if he has emerged from a funky, soul-filled ether. Using our viewpoint like a mirror, he pats his coif and stares directly at us with a confidence that will be repeatedly tested. His job interview serves as his first quiz.

“We’ve never had a Black police officer,” Stallworth is told. “So you’ll be the Jackie Robinson of the Colorado Springs police department.” This analogy is a loaded and telling statement; Robinson was ruthlessly taunted by baseball fans who hurled the ugliest rhetoric at him, to which he could offer no response lest he be seen as “uncivilized” by the White fans who didn’t want him there in the first place.

Police Chief Bridges (Robert John Burke) wants to ensure there will be no Negro insurrections if his officers get a little rowdy with the new recruit. “What would you do if someone here called you a nigger?” Bridges’ cohort asks Stallworth. “That would happen?” Stallworth asks incredulously. The response to this question provides the biggest laugh of the year.

How you look will lead to assumptions about how you should act, and what you should believe. This is an underlying theme of “BlacKkKlansman.” Stallworth wants to be an undercover detective, but as Zimmerman notes, no rookie has ever been given this work, and certainly not a rookie of color. However, after a tense stint in the records room, Stallworth is assigned to infiltrate a Black student group’s rally with activist and former Black Panther Kwame Ture (an electric Corey Hawkins). Chief Bridges’ intentions for this stakeout are outwardly racist—he doesn’t want the town’s Black folks to suddenly become radicalized and excited by the fervor of Ture’s speech—but Stallworth takes the assignment in order to connect with the community.

Stallworth’s stakeout is the film’s first brush with the concept of passing. After all, passing is a form of going undercover, albeit permanently. The rally introduces Stallworth to student group organizer Patrice (Laura Harrier), whose rightful suspicion about the cops will keep him passing as a civilian in order to woo her. But “BlacKkKlansman” really delves into the art of passing when Stallworth becomes involved with its most common form, that of an African-American passing for White. After seeing an ad in the paper for the Klan, Stallworth calls the number and convincingly spouts all kinds of offensive invective. The sight of a Black man talking about how much he hates Blacks plays up the absurd side of racism. As a result, Stallworth’s evil White persona gets invited to a meet-and-greet.

Here’s where Flip Zimmerman enters the picture. There’s credible evidence that the KKK may be planning an act of violence during the appearance of another famous civil rights activist (whose identity I won’t reveal). Stallworth wants to get close enough to the Klan to thwart it. But his phone shenanigans can only take him so far; for personal appearances, he needs a more convincing guise. Zimmerman, a non-practicing Jewish man, gets the job. Billing themselves “The Stallworth Brothers,” the two share an identity while working the case. Zimmerman is the “face” of Ron Stallworth, and the real Stallworth is the suspicious Black man following him around in the shadows taking surveillance pictures. Just for fun, Zimmerman learns how to mimic Stallworth’s “White voice” by reciting lyrics by America’s true poet of Soul, James Brown.

With this undercover case, “BlacKkKlansman” becomes the story of two people engaged in the same bout of passing as a racist White person. Though Zimmerman, by virtue of the correct skin color, has what seems to be the easier task, he also bears the psychological brunt of having to pretend to be something that would despise his true identity. It’s here where Lee works that aforementioned dichotomy, often playing Stallworth’s phone interactions for laughs (especially when talking to an excellent Topher Grace as David Duke) but keeping a masterful, tense grip on Zimmerman’s scenes. There’s always a sense he’ll be outed, especially by the tenacious Felix (a scary Jasper Pääkkönen), who immediately pegs him as Jewish and never lets up on his suspicions. Eventually, the two tonal halves converge in a climactic race against time that is among the most harrowing and provocative work Lee has done.

While Washington is very, very good here, I was more fascinated by Driver’s character. I think it’s partially because I have firsthand knowledge of what Ron Stallworth went through as the sole Black person at his job. The open hostility, the jokes by his White counterparts, the assumption that your skin color determines your intelligence level—I’ve been there, done that and am still doing it. What drew me to Flip Zimmerman was the notion of him having to “pass” in an environment that also automatically made assumptions about his skin color. But his passing isn’t visual, it’s mental. As someone who never gave much thought to his Jewishness, Zimmerman cannot help but dwell on it all the time amidst the constant anti-Semitic comments of his newfound friends.

“Why don’t you think you have skin in this game?,” Stallworth asks his partner. Because Zimmerman has the capacity to dodge the hatred that would be directed at him should he choose to do so. But I have often wondered how much this act of self-preservation cost the person who pulled it off. For Zimmerman, there’s the ultimate goal of possible revenge against the Klan, or at the very least, an embarrassing exposure of their full ignorance. But for someone like a relative of mine who chose to live his life as a White man in North Carolina, the only goal was survival. How much of his soul did that cost, if any?

I believe Lee is similarly intrigued by Zimmerman. Unlike Stallworth, Lee never gives us a scene where Zimmerman fully feels respite nor relief from his role-playing once the case kicks in. At least Stallworth has a romance to distract him, even if he’s being dishonest about what he does for a living. There are two scenes in “BlacKkKlansman” where it feels as if Lee and editor Barry Alexander Brown let them run on too long, until you realize that these scenes are showing Black people in moments where they are not worrying about anything but the joy and the power of being themselves. By contrast, Zimmerman’s scenes with the Klan always feel awful even when the crew is supposedly enjoying themselves—these scenes can’t end soon enough.

“BlacKkKlansman” clearly wants to be the anti-“Birth of a Nation,” and I’m sure some less-enlightened people will consider it on that same level of racial propaganda. But what else do Lee and his producer Jordan Peele want to accomplish with this astonishing, funny and important film? The answer is most likely in the film’s coda, which shows footage from the incident in Charlottesville that cost Heather Heyer her life. In fact, this film opens on the anniversary weekend of those events. This raw footage, which arrives after perhaps the best use ever of Lee’s trademark people-mover shot, is both a massively effective, righteous trolling and a terrifying reminder that we are not so far removed from the period-piece world we have just witnessed. And Lee, a man who never gave a damn about what anyone thought of his politics, is fearless in speaking truth to power with this film. Lee dedicates “BlacKkKlansman” to Heyer’s memory, writing “rest in power” under a picture of her before ending his film with the only Prince song that could have ended it.

This is not only one of the year’s best films but one of Lee’s best as well. Juggling the somber and the hilarious, the sacred and the profane, the tragedy and the triumph, the director is firing on all cylinders here. “BlacKkKlansman” is a true conversation starter, and probably a conversation ender as well.