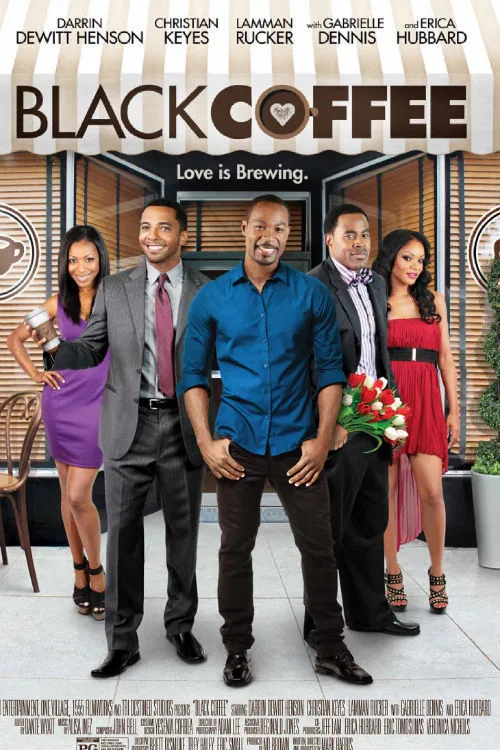

“Black Coffee” is the kind of movie where a character quotes the tired old warhorse “If you love something set it free (etc.)”, and it is treated like a profound and original statement. Someone also says “Whatever is meant to be will be” (multiple times) and that is also treated like a profundity. Directed by Mark Harris, “Black Coffee” starts with a quote attributed to “Anonymous” that goes on and on for a bit about what a “gifted man” deserves, a “gifted woman” and “God” being involved. That’s your first clue that you’re about to watch a movie with an agenda, and it’s the agenda that matters, not character, not story. It makes for a confused muddle, with characters who often behave in ways that have no correlation to actual human behavior, and language that exists in order to prop up the agenda. There is no subtext here. It’s all text. It’s too bad, because Gabrielle Dennis, who plays Morgan, the up-and-coming lawyer and love interest of the main character, is a beautiful and thoughtful actress who is doing her level best to play subtext where there is none. She actually manages to create a character who seems alive. She’s the only one.

From the first scene, which takes place in a bedroom, things feel off. Everything looks gorgeous, the furnishings, the bed sheets, the golden light, and there’s a slick matte quality to the image. Who are these people? How people furnish their homes gives an audience so much information about the characters. “Black Coffee” puts everyone in a generic “House Beautiful” environment. Robert (Darrin Dewitt Henson) leaves his sleeping girlfriend Mita (Erica Hubbard) in bed to go to work, but not before she sweetly kisses him goodbye and asks if he “left the check” for her on the counter. Robert goes into work and is summarily fired by his boss Nate (Josh Ventura). Robert works at a painting company, established by his father, but there were some business dealings that left the company in Nate’s hands, so Robert is now essentially an employee. Nate gives him no reason for firing him and the scene plays out in long awkward fashion, accompanied by baffling presentational acting choices. Is it supposed to be funny? How does Nate feel about being fired? He seems mildly annoyed, and that’s about it. Nate comes home to find that sweet-yet-money-hungry girlfriend he just left in bed packing up her car and moving out. She flashes her empty ring finger up at him, shrieking at the top of her lungs about how it’s been two years now and where’s her ring?

Robert, again, only seems mildly annoyed by this upsetting development. We don’t know whether or not to invest in Robert, because he barely seems invested in the major parts of his life himself. Robert has a sidekick, a cousin named Julian (Christian Keyes), who has a strangely lucrative business selling coffee to local businesses. Julian lectures Robert on how he needs to leave the “plantation” of white-owned businesses and start up his own. The title of the film, and this lecture (the script is full of similar lectures), is the clue to Mark Harris’ real agenda here (Harris also wrote the script). African-American entrepreneurship is a potent topic, full of possibility, which deserves better treatment (and was handled better in, say, “Barbershop“, which showed that investment back into the community through owning your own business is also investment in yourself.) But Mark Harris bashes us over the head with it. The entire script could be read from a podium in a lecture hall.

Julian offers the now-unemployed Robert a job delivering coffee to his clients, one of which is the aforementioned Morgan, an attorney who has just set up her own firm. When Robert drops off the coffee, he also decides to take that opportunity to not only offer his services to paint her new office but also hit on her. Morgan, thank goodness, seems like a real person, and treats the come-on like the inappropriate behavior that it is, but “Black Coffee” needs these people to be together, so eventually Morgan accepts a dinner invitation. She insists that it is not a “date”, and yet she shows up at his house in a skintight purple mini dress heavy on the cleavage. Any understanding of who Morgan is, any specificity of her character, is lost in that sloppy and opportunistic costuming choice.

Morgan and Robert begin a tentative romance, where all they do is talk about what a “real man” is like, and what a “real woman” needs. They discuss the meaning of the word “soul mate” with no irony. Morgan asks Robert if he is “a man of God”, clearly important to her, and she tells him that she thinks woman’s real role is to be her man’s “helpmeet”. Never mind that she has the gumption and smarts and bravery to go to law school, work as an attorney in a cutthroat business, and then actually set up shop for herself. All of that doesn’t hold a candle to being a “helpmeet”, apparently. Naturally, though, her words inspire Robert to start thinking about opening up his own painting business, so that he can be the “real man” that she needs him to be, so that she can “help” him. It gives their romantic scenes a whiff of pity from her side that is not sexy at all.

The plot gets extremely convoluted, involving Morgan’s ex-husband Hill (Lamman Rucker), whose behavior borders on stalker harassment, and yet then we are supposed to feel happy that he finds love, too, the big lug. The film gives Hill and his new love a long slo-mo montage of the two of them frolicking on a swing set in the golden sunset light, all as a sappy love song plays, the whole song! Hill has been shown to be a bully and a control freak, who treats Morgan as his property even though they are divorced, and nothing has been set up properly for that montage to have any emotional resonance. I’m supposed to feel happy that a veritable villain enjoys swinging on the swings and laughing in slo-mo?

The agenda here, outside of the positive idea that African-Americans need to be employers not employees, is a confused one and seems to be: Men need to be strong and take charge or women will not love them. But men also need to be vulnerable enough to work to better themselves so that their woman can have the glorious Godly opportunity to be a “helpmeet” to them. Mita is set up as a reprehensible character, a sneering gold-digging nightmare, and yet when a man finally bosses her around, she melts like ice cream on a summer day. Charming. Robert, under Morgan’s supportive influence, starts reading books on business-ownership, all as she looks on with loving (and somewhat pitying) eyes. (Gabrielle Dennis, as I mentioned, is a smart actress who seems to operate from a truthful place, and she can’t keep that truth out of her performance.)

“Black Coffee” means well. It has some interesting and exciting ideas, and a couple of funny lines (Morgan says to Robert, “How do I know you’re not a serial killer?” Robert replies, “Because I’m black.”) It features one good performance from Dennis, who struggles to show us a real woman doing her best to live up to her expectations for herself and accept love into her life again. But Dennis can’t save the whole thing. It’s too big of a mess.