There’s an opening overhead shot of the Brazilian rain forest, dense and limitless. As a tourist boat slides along a river, indigenous tribesmen materialize on the banks to regard it reproachfully. They hold bows and arrows and don’t seem fond of these visitors. But hold on; one of the young men has a layered haircut with a blond top.

As recently as the 1970s, when Herzog filmed “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” in such a forest, these Indians would have been “real.” But the time is the present, and the forest a preserved facade shielding fields that have been stripped of trees and devoted to farming. If they want, the Indians can pile into a truck and hire out as day laborers. But all of their traditions center on the forest and its spirits, and this new life is alienating. Some simply commit suicide.

This is all true, as we have been told time and again; meanwhile, the Brazilian government remains benevolent toward the destruction of the planet’s richest home of life forms and crucial oxygen source. Indians have been stripped of ownership of their ancestral lands and assigned to reservations far from the remains of their parents; it is the same genocide the United States practiced, for those with power in Brazil have not developed a conscience in the years since.

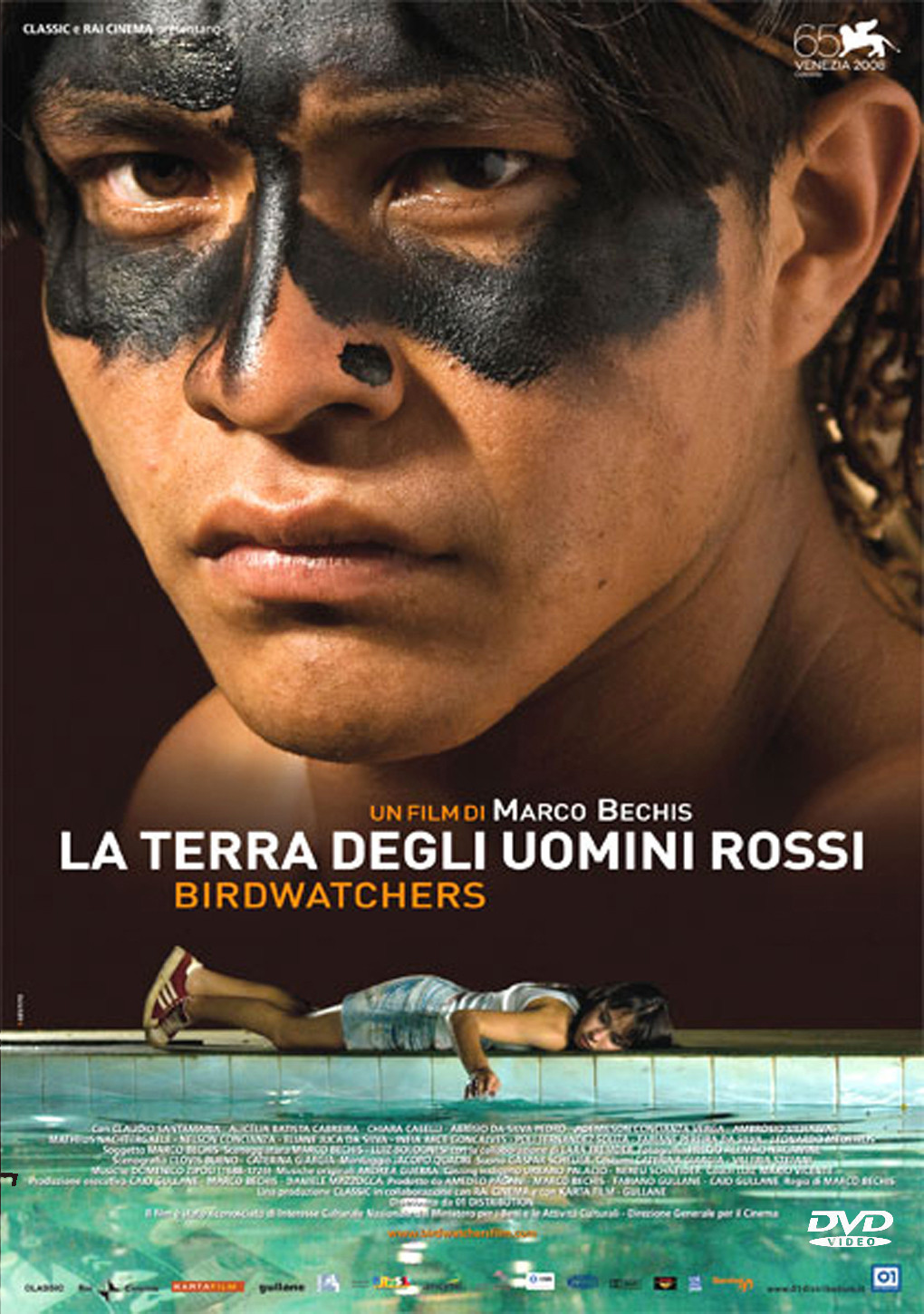

Marco Bechis’ “Birdwatchers,” now receiving its U.S. premiere at Facets Cinematheque, is a ground-level drama involving a Guarani tribe that packs up one day, leaves “its” federal land, and builds shelters of tree limbs and plastic sheets on farmland that once was the tribe’s. This goes down badly with the farmer, who with his family lives in a spacious home with a pool and (Indian) servants.

The film portrays the descendants of colonialists very broadly; its strength is in the directness of the performances by Indians. I assume their performances are informed by actual life experience, because Bechis shot on location with local non-actors. They’re cohesive in the group, grow depressed when separated from it, are attuned to spirit omens (or believe they are, which amounts to the same thing). Without conversational preludes, they say bluntly what they mean: “I want to be with you” or “you must leave here and never return.”

This doesn’t mean they lack subtlety. It means they keep a lot of things to themselves. We follow two adolescent boys, Osvaldo (Pedro Abrísio da Silva) and Ireneu (Ademilson Concianza Verga), the first the son of the leader, the second he of the haircut and a yearning for sneakers. The leader Nadio (Ambrosio Vilhalva) is strong enough to lead the group onto the farmlands, enforce discipline and deal with many newcomers. But he’s an alcoholic, with his booze happily supplied by a merchant who controls them by giving credit. Shades of the company store.

Sex is in the air. The farmer’s teenage daughter, in a bikini, and one of the boys, in a loincloth, begin meeting at the river, he to collect water, she to swim, and although they don’t get very far, an intriguing tension rises between them. On both sides there is the allure of unfamiliarity.

The group is chronically low on food and funds, and Nadio correctly realizes that day labor is a form of bondage. He begins to call his followers “the movement.” Sooner or later, there will be a clash, and there is, but one that unfolds in a way unique to these people.

“Birdwatchers” is impressively filmed and never less than interesting. If it has a weakness, it’s that this is a familiar sermon: Save the rain forest. Respect its inhabitants. Bechis and his co-writer, Luiz Bolognesi, don’t really develop the characters much beyond their functions. But the reality of the Indians and the locations adds its own strength.

Note: I learn from the film’s press material that the European-sounding sacred music was composed by Domenico Zipoli, an Italian Jesuit who lived with this same Guarani tribe in the 1700s.