“Hey, are you alright?” my friend Phil asked, seeing me 20 minutes after I emerged from a screening of “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk.” I was wondering the same thing myself, and pondering my recent medical history in doing so. A few weeks ago, just after a trip overseas, I came down with one of the worst colds I’ve ever had. I got some meds that mostly cleared things up within a few days. Then I go to Ang Lee’s movie and come out feeling much as I had during the worst of the cold—woozy and feverish.

Did the film literally make me sick, or return me to the illness I thought I’d left behind a few days before? If so, I can imagine a couple of reasons why.

First, “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” was shot in 3D at a frame rate of 120 per second (five times the normal rate) at 4K, with the aim of producing a picture that offers far greater clarity and detail than standard movie images. Sony Pictures, though, elected not to go the expense of outfitting theaters so it could be viewed in the way it was shot, so it will be seen as Ang Lee intended it in only a handful of theaters in the country. The version I saw was the “normal” version that will be released most places, which prompts a question: Would the “real” version have left me feeling less ill, more ill or about the same?

I would guess more, or about the same, to the extent that the feeling was owed to the movie’s unusual visuals. The experience left me recalling an event I attended back around the year 2000, where several industry experts explained the nature of digital projection, which was soon to be introduced to movie theaters. One noted that film has an innate graininess and lack of definition that digital shooting and projection can eliminate. But, he said, his team did an experiment where they filmed a driver’s-eye-view of a car careening down at a mountain road. Shown as a standard film image, it gave viewers the sense of an exciting rollercoaster ride. But with the graininess of film removed and a hyper-clear digital image put in its place, the same scene was so realistic that it made some moviegoers vomit.

Previously, the most noteworthy proponent of higher-frame-rate movie images has been the legendary cinematographer Douglas Trumbull, who shot “2001: A Space Odyssey.” But Kubrick’s sci-fi epic—with its slow-moving planets, spaceships and vast distances—is arguably one of the few examples of a film that benefits from hyper-real images. Used in a standard dramatic movie like “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” the technique engulfs the viewer’s eye in a surfeit of razor-sharp detail that entail, quite literally, too much information. I don’t know how many people will share this sensation, but for me the effect was akin to a mild case of car sickness.

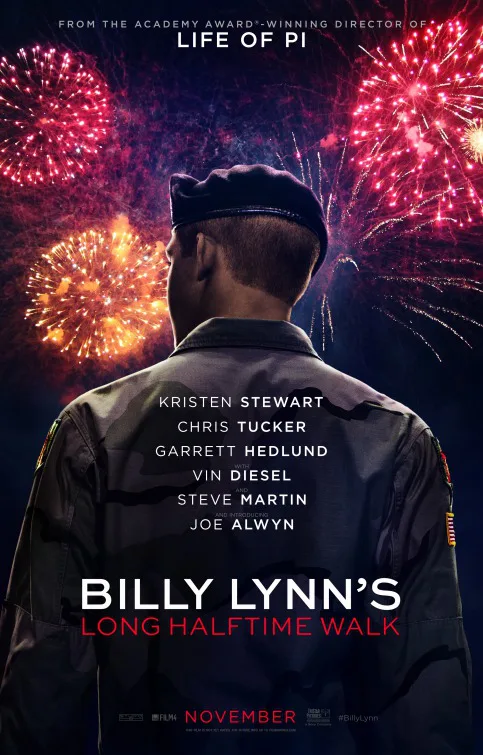

The second factor, which may be connected to the first, is the film’s main setting. Transpiring in 2004, the story (scripted by Jean-Christophe Castelli from Ben Fountain’s novel) follows the members of Bravo Squad, American soldiers from the Iraq War sent on a publicity tour after one of their number, Billy Lynn (Joe Alwyn), is acclaimed a hero for an on-camera attempt to rescue a fellow soldier during a firefight. For most of the single day we observe them, they are at a Dallas Cowboys football game, where they will take part in the halftime show. Though the film recurrently flashes back to the squad’s experience in Iraq, and Billy’s earlier dealings with his Texas family, we are repeatedly immersed in the football stadium’s garish grotesquerie and bizarre artificiality, complete with Jumbotron—an environment that oddly compounds the photography’s dizzying impact.

In an election year four decades ago, Robert Altman made a film called “Nashville” that X-rayed the ways showbiz leads Americans into thickets of self-serving fantasy and delusion. To an extent, “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” seems to have similar things on its mind. The soldiers have a handler/agent (Chris Tucker) who spends much of the story on the phone trying to get a movie deal for them. That effort eventually leads them into the presence of a thoroughly odious zillionaire played by Steve Martin, who seems to be channeling Dick Cheney.

Then there’s the way soldiers are used in the halftime spectacle, when they’re paraded on the field behind Destiny’s Child. (Beyoncé is seen only from behind, as a bod beneath a bouncy wig: surely the movie’s most ridiculous special effect.) Yes, the boys are simply propaganda tools put on display like gladiators in ancient Rome, and it’s here that Billy reaches the climactic memory of his heroic deed, which doesn’t seem so glorious in retrospect: filmed in a single shot, it shows him tangling with an Iraqi fighter, then getting on top of him and sliding a knife into his throat.

The contrast between this grisly reality and the way it’s framed as jingoistic spectacle makes a satiric point that’s a bit too obvious to be effective. But that’s in keeping with the rest of the movie, unfortunately. The characters are paper-thin, the dialogue trite and superficial. And needless to say, this is another movie about the Iraq War that only cares about its impact on Americans, not its causes or, heaven forbid, its effects on Iraqis. The film’s only slight glimmer of political consciousness comes in the character of Billy’s sister (Kristen Stewart, excellent as always), who tries to talk him out of returning to Iraq.

When a book is written some day on “The Semiotics of Cute,” surely there’ll be a chapter devoted to actor Joe Alwyn, who boasts cuteness roughly akin to that of Matt Damon in “Good Will Hunting.” Even the cheerleader he romances at the big game (Makenzie Leigh) can’t help but remark that he’s “so darn cute.” And would the reason for that be that, at a key moment, the audience is supposed to choke up at a giant close-up showing a single tear rolling down his cheek? Do ordinary-looking soldiers stand no chance of tugging at our heart strings?

Ang Lee is a great director whose last film, the Oscar-winning “Life of Pi,” made ingenious and very effective use of 3D technology. But that film had a much better story than “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” which displays many of Lee’s skills but does little to advance the case for high-frame-rate cinematography.