To be an accomplished artist, especially one considered an “outsider artist,” is to be the master of one’s own language. The self-taught painter Bill Traylor was clearly such a master, with his abstract depictions of his life experiences during the Reconstruction and Jim Crow America; memories articulated with long-limbed human figures, oval dogs, sketched out crowds, and squabbling couples, fondly described by an art expert here as “beautiful simplicity.” It’s entirely true with Traylor’s case that one person can look at a painting and see a few shapes, colors, and maybe some faces, while others see a full text.

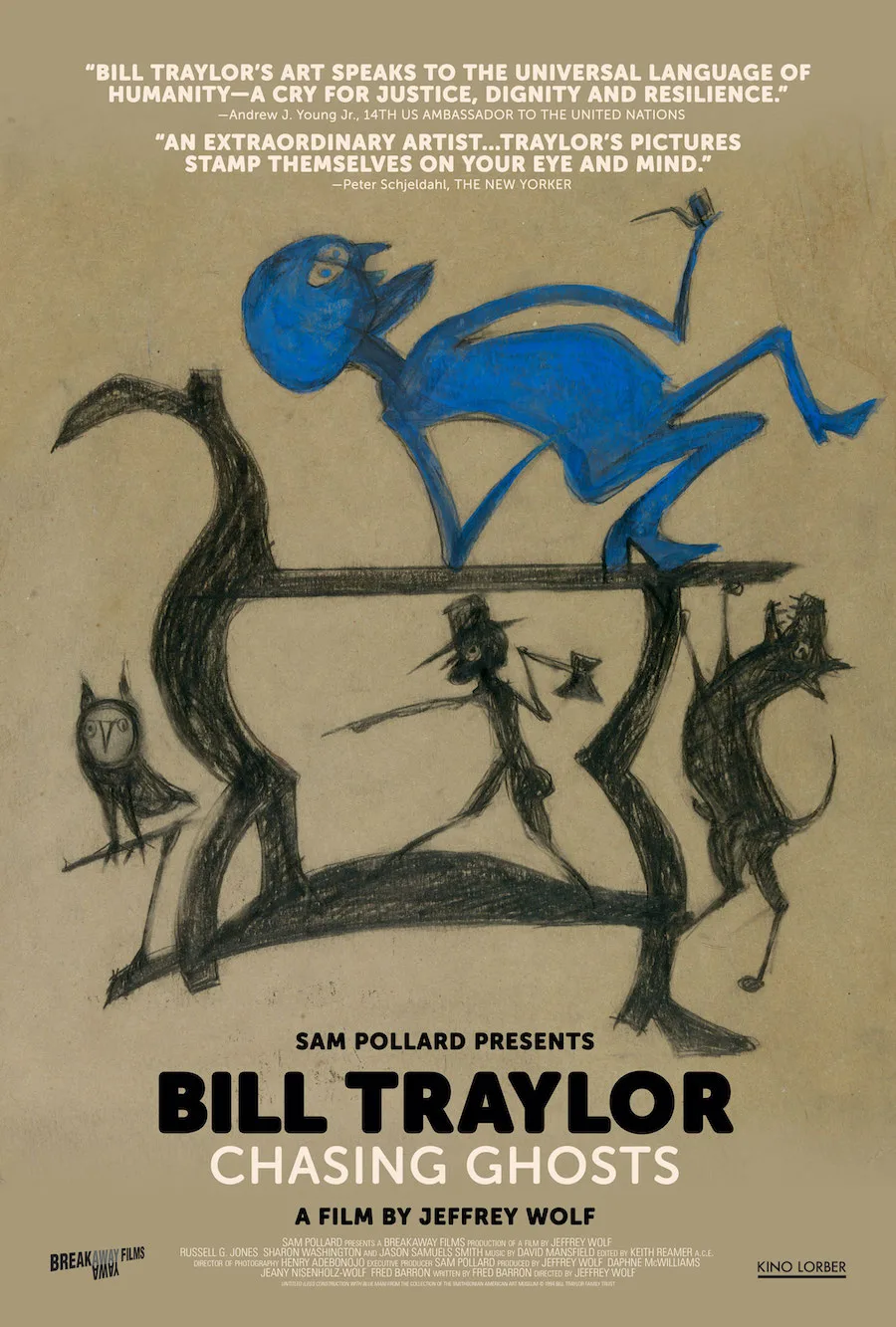

Getting someone to understand that language can be a whole other deal. “Chasing Ghosts” has a great idea in showcasing as much of Traylor’s work as possible, and next to the creations of other Black artists, but its talking head presentation is fairly didactic. Traylor’s abstract paintings don’t so much come to life through this documentary but are lovingly promoted, and the filmmaking’s own artistic approach can contradict the verve that Traylor’s fans associate with his work.

Given Traylor’s status as an artist whose work was more promoted after his death than during his life, his paintings requires the fullest picture possible, and a great deal of context. How else to best understand these rectangular torsos, the triangular teeth, or the one-dimensional locations? Wolf’s interviewed experts provide some compelling insight, like how the color blue on a figure’s legs referred to the emotional doldrums of the blues itself, or how the relationship dynamics to be found within how a woman and a man are shown clashing, pointing in different directions. But an airy description like “beautiful simplicity” echoes throughout, and Wolf’s documentary favors bulky historical context more than it does analysis when it comes to making Traylor accessible. It can’t decide if its main audience is a celebrated art gallery or a school trip, though both have their merits.

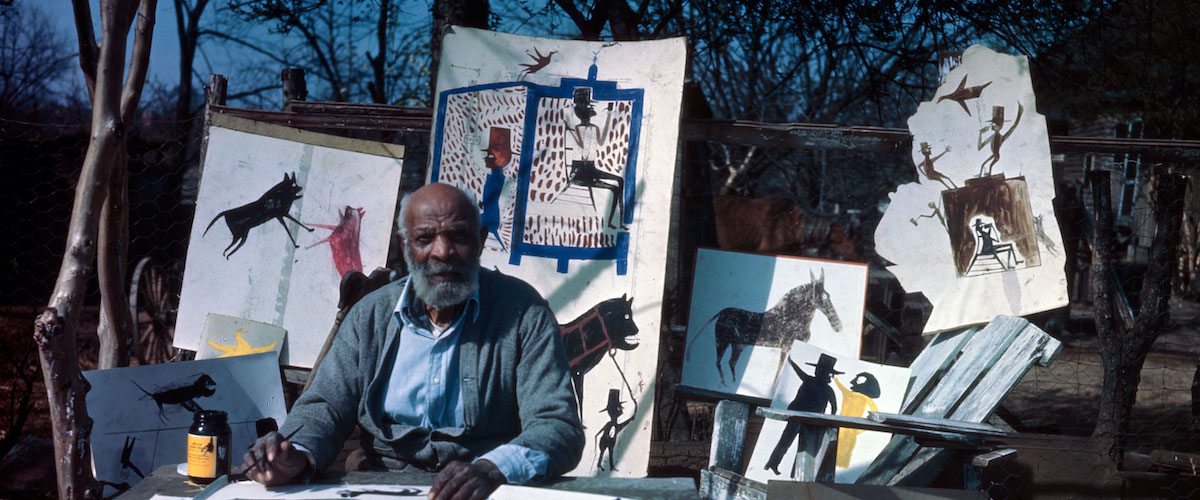

Traylor created hundreds and hundreds paintings in his 80s, a type of final chapter after initially being born into a family of slaves that shared a long-time bond with the white family who owned them (which is where the last name Traylor came from). His paintings, many of which he drew on the back of cardboard or any paper scraps he could find, were completed in Montgomery, Alabama, a resting place after decades of being a sharecropper, and dancing, carousing, and taking care of his growing family as America supported and terrorized people just like Traylor. Taken as a whole (the documentary displays dozens and dozens of them, though countless were lost over time) the paintings are like fascinating journal entries from a perspective of Black America not as thoroughly documented, with some of Traylor’s takes more mystical or playful than others.

In bringing this story to light, Wolf is working with a small amount of specific archival material—an understandable part of this production, along with its budgetary constraints. There’s certainly not a lot of photos of Traylor or his upbringing, and his life events seem mostly charted by the few remaining written spreadsheets. But Wolf tends to create a larger American history background with flourishes that brings out its more History Channel-like inclinations: voiceover reenactments from the words of leaders and ex-slaves, slow scans over art of historical clashes, and generic B-roll footage. Paired with its talking head interviews which are already aesthetically rough-around-the-edges themselves, the presentation runs dry in spite of its valuable information.

Wolf’s sharper choice is to emphasize this historical context by supplementing Traylor’s creations with other Black artists; their expressions are like practical special effects that add more depth to this larger story of Black art, discovered and shared. Wolf gives time for the words of Zora Neale Hurston or Langston Hughes to wash over us in brief meditative passages, their observations reflecting the most recent discussed point in Traylor’s life. Stoic monologues by actors Russell G. Jones and Sharon Washington dominate a minimal stage, sharing bits of Traylor’s saga to an unseen audience; the furious silhouette of tap dancer Jason Samuels Smith vividly accompanies a passage about how backwards limbs and curled legs represent dance in Traylor’s work. It becomes clear that if the doc isn’t going to stretch itself too far with its own storytelling tactics, its vision of the past is at least chock-full of Black artistry.

A sincere doc like this nonetheless has to be persuasive, to help us fully feel what the experts do as they speak with great reverence about its subject. “Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts” gets more stuck when it comes to its own expressions, and I would have appreciated more to take away regarding how Traylor’s compositions themselves could stand on their own. But Wolf’s film captures what feels most important: it’s successful in getting one to understand the vitality of this artist’s language, and why it demands more visibility in history.

Now playing in select theaters and via virtual cinemas.