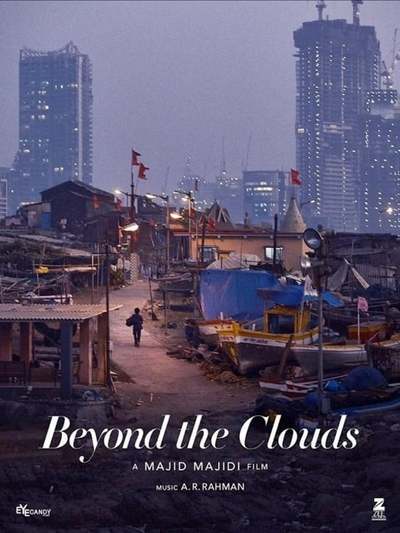

There’s something off about “Beyond the Clouds,” a beautiful but obnoxious Indian-set drama. The film—the latest from Iranian co-writer/director Majid Majidi (“Baran,” “Children of Heaven“)—certainly looks good thanks to cinematographer Anil Mehta’s typically gorgeous presentation of Mumbai’s crowded streets and labyrinthine back alleys. But Mehta’s visual compositions are dissatisfying after a point, mostly because the pseudo-mystical, live-and-let-live philosophy they espouse doesn’t ring true when applied to a story about poor people struggling to transcend their treacherous living conditions.

Mehta (“Lagaan,” “Veer-Zaara”) can only do so much in a story that, like Majidi’s most famous ’90s films, feels simultaneously too spacey and too neat to say anything insightful about the plight of Amir (Ishan Khattar), a teenage drug dealer who must look after Ashik (Goutam Ghose)—the abusive and now hospitalized husband of Amir’s self-less sister Tara (Malavika Mohanan)—long enough for Ashik to bail Tara out.

From the start, Tara’s tragic circumstances are conflated with Amir’s lack of responsibility. He must become human enough to not only accept responsibility for his actions, but also realize his responsibility to her. This is a major challenge since Amir often does whatever it takes to get ahead, including threatening Ashik’s life, and offering to sell a child into prostitution. Amir is, in this way, unkindly treated like a product of his environment. Still, the film’s dogmatic message is clear: there are moments of beauty in this teenager’s life that are meant to prove that he is spiritually stronger than all of the seemingly unavoidable/unforeseeable material obstacles in his way. Even the mobbed-up gigolo/dealer that Amir works for, and the obstinate brother-in-law he wants to smash to bits … all of these problems are supposedly surmountable.

This unbelievably optimistic mentality makes it hard to take seriously Majidi and co-writer Mehrad Kashani’s rote scenario. Majidi and Kashani hold Amir’s feet to the fire by asking him to not feel trapped by his complex living situation. He must forgive Ashik (notice that there’s no discussion of the corrupt nature of the Indian court system). He must save his sister. He must find a way to support himself. He must be kind to Ashik’s estranged mother and extended family.

Meanwhile, Tara rots in jail. She’s only believably human in the scene where she gets fed up with her Kafka-esque situation and screams that she needs to be let out immediately. She paces back and forth, like Jack Nicholson howling with rage in the much-missed Milos Forman’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.” And she demands attention, but Amir can only do so much. He follows her movements from the other side of a see-through glass wall that separates prisoners like her from visitors like him. This is the most honest scene in “Beyond the Clouds,” a rare moment of clarity where the filmmakers admit: there are limits to what we can do for our loved ones, no matter how much we owe them.

Unfortunately, Majidi and Kashani also often insist on piling the weight of Mumbai’s collective troubles on Amir’s shoulders. Never mind that the kid is only 19 years old, and doesn’t have a parent or mentor-like figure that can help him figure out how to be his best self. What seems to matter most to Majidi and Kashani is that Amir has enough friends and resources to make bad decisions. So why shouldn’t he be judged like an adult fictional character? In this unsparing context, it’s hard to stomach scenes where Ghose seduces the camera with his genuinely seductive smile, and antic energy. He does a charming improvised dance for a former colleague—right before he stabs his friend in the hand. Amir even looks suave enough to convince his murderous, tight-wad gigolo boss to pay him on time.

But what’s the point of “Beyond the Clouds”? Why tell your audience that it’s more important to go beyond themselves than it is to be better as themselves? Majidi is clearly drawing on the artistic tradition of Italian neo-realist films like “Bicycle Thieves,” “Umberto D,” and “Rome, Open City,” but shows no signs that he made it through to the end of the best of those movies. Spoiler alert: people remain homeless, hungry, and sad at the end of them! They don’t get to transcend their circumstances because that, to put it mildly, would be a cop-out.

I don’t care how stunning the Mehta-lensed landscape shots of Mumbai are. The point of these scenes is to watch Ghose find his way through and into the story. But “Beyond the Clouds” isn’t a city symphony: it’s a conflicted tribute to a cruel, and bewitching slum. Majidi and Kashani’s shared vision feels incomplete, as if they were moments away from realizing how to temper their story’s condescending, but well-meaning perspective, but never got around to doing it.