Addiction is a tricky phenomenon to depict on screen because it’s such an insidious, internal disease. What often ends up happening is that we see the same sorts of manifestations of the damage it can cause, both to the abuser and to the people who love that person, resulting in cinematic clichés.

Director and co-writer Felix Van Groeningen mostly avoids those familiar horrors in “Beautiful Boy,” instead depicting one young man’s struggles with methamphetamine as a series of sun-dappled, time-hopping vignettes. His father’s efforts to pull him away from the brink—over and over again, with increasingly fruitless results—provides some semblance of a stable throughline.

It’s a heartbreaking true story and one that surely will resonate with viewers who’ve experienced addiction themselves. But there’s a gauzy detachment in Van Groeningen’s approach that keeps it from achieving the kind emotional wallop it seemingly intended. It’s almost too pretty in a self-consciously artful way, and that overriding aesthetic suffocates the underlying truth of the lead actors’ performances.

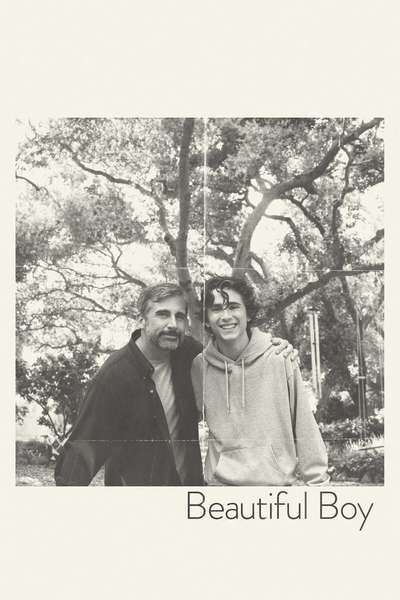

Steve Carell and Timothee Chalamet offer deeply felt work in bringing the story of father and son David and Nic Sheff to life. “Beautiful Boy” is based on both of their memoirs: David’s Beautiful Boy: A Father’s Journey Through His Son’s Addiction and Nic’s Tweak: Growing Up on Methamphetamines. Both men are writers—David Sheff is a longtime journalist—and individual details give their tale a rich specificity. Van Groeningen, the Belgian filmmaker whose “The Broken Circle Breakdown” earned a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar nomination in 2014, creates a vivid sense of place in remote, woodsy Marin County, California, just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco.

But the non-linear narrative in the script co-written by Luke Davies too often strips the story of its potential power. “Beautiful Boy” jumps all over the place in time, needlessly cutting to flashbacks and flash-forwards in ways that are more than just confusing. They repeatedly take us out of the moment, especially as the film is building to its emotional crescendo. Maybe these wisps of memories are meant to reflect the characters’ inner state of chaos. Often, they evoke a sense of melancholy for an earlier, simpler time. But what they wind up doing overall is detracting from the actors’ strong performances. Carell and Chalamet are both so good, you long to see them simply interact with each other for an extended period.

In his first major role since his star-making turn in “Call Me by Your Name,” Chalamet plays Nic Sheff, a college-bound 18-year-old with a promising future ahead of him. He’s young, gorgeous and tormented; hugely charismatic and wise beyond his years, he’s a bright young man with a taste for poetic depressives like Charles Bukowski and Kurt Cobain. Twitching and raging through highs and lows, Chalamet is James Dean-ing the hell out of the role.

As the father who’s constantly trying to rescue him, Carell undergoes his own roller coaster ride. Since “Beautiful Boy” is told mostly from his perspective, Nic remains a tantalizing enigma. There’s hope, and then there isn’t, and then there’s hope again. Rehab leads to a halfway house leads to another relapse. Anyone who’s ever dealt with an addict can sympathize: You can love someone, but you try as you may, you can’t fix them.

Still, David struggles to do just that, mostly on his own but with some help from his artist wife (Maura Tierney), with whom he has two young kids, and his ex-wife (Amy Ryan), who can only do so much to save her son by phone from Los Angeles. (With the exception of a chase toward the end, “Beautiful Boy” woefully wastes its strong women.) When David puts his skills as a veteran journalist to work in trying to understand the draw and the damage of this drug, it lifts “Beautiful Boy” from its moody morass and gives it some much-needed momentum. The fact that he’s mostly measured and methodical makes the rare moments when he explodes that much more startling.

But too often, the film relies on painfully on-the-nose song choices to punctuate a scene or express what its characters are feeling. These include Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold,” Nirvana’s “Territorial Pissings” and a silky-smooth Perry Como cover of “Sunrise, Sunset.” The soundtrack goes beyond commenting on the action to actively distracting from it. There might have been more power—and beauty—in a more understated approach all around.