“Your indifference cost these men and women their most valuable commodity—TIME! It’s the one thing they’re running out of.”—Jon Stewart

Of all the speeches in recent memory, few have channeled the indignant fury of the quintessential Capra protagonist as eloquently as the one delivered last month by Stewart, who served as our nation’s sardonic conscience during his 16-year run as host of “The Daily Show.” While addressing a House committee largely comprised of conspicuously empty chairs, Stewart shamed the inaction of Congress in aiding 9/11 first responders, real-life heroes abandoned by the country they sacrificed everything to protect. There wasn’t a hint of irony or self-aggrandizement in his blisteringly emotional takedown, echoing the democratic principles embodied by James Stewart as both Jefferson Smith and George Bailey.

As governments continue to be overtaken by special interests around the world, profits will inevitably be prioritized over the well-being of the working class, destroying countless lives in the name of competition. It’s no wonder why our international cinema has currently become populated by 21st century Capra-esque protagonists like Ken Loach’s Daniel Blake and Stéphane Brizé’s Thierry Taugourdeau. The latter character was portrayed by Vincent Lindon in Brizé’s 2015 gem, “The Measure of a Man,” a quietly incendiary portrait of a laid off factory worker who finds crucial employment at a supermarket, where he is tasked with ratting out shoplifters.

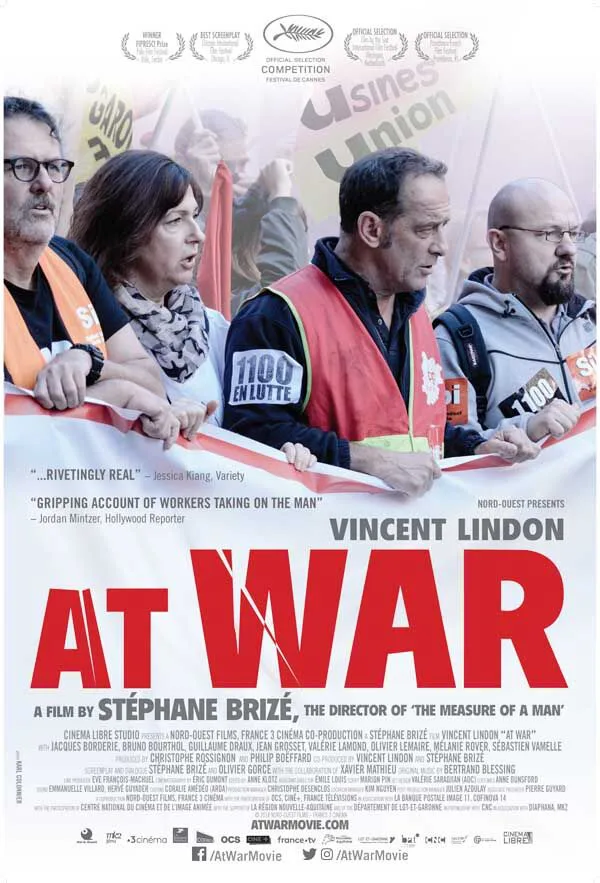

The simmering frustrations and indignities endured by the disenfranchised souls so compassionately observed by Brizé is brought to a full boil in his latest collaboration with Lindon, appropriately titled “At War.” With his mustache shaven off and eyes often bulging with outrage, Lindon brings a considerably fiercer presence to his role here as Laurent Amédéo, the spokesman for 1,100 employees at Agen, a French car part supply plant, who are left jobless when it is closed by Perrin Industries. This sudden move by the company breaks their promise made two years prior that workers’ jobs would be secured for at least five years, provided they work longer hours for no additional pay while forfeiting their bonuses in the process.

In the film’s first of many heated confrontations set within the sterile interiors of boardrooms cloaked in the façade of civility, Laurent and his fellow union representatives quickly demonstrate that they are the opposite of naive, adding up the hours of unpaid labor that saved the company million of euros, increasing Agen’s profits considerably over the past year. With courts approving the company’s right to close the plant, despite no evidence of their decision’s economic necessity, Laurent leads the union on a 23-day strike, refusing to return to work unless they are granted a meeting with Hauser (Martin Hauser), the CEO of Perrin’s German parent company, Dimke Group, which oversaw the recent growth of shareholder dividends.

Viewers familiar with Michael Moore may find it impossible to watch “At War” without being frequently reminded of the documentarian’s still-unsurpassed 1989 muckraking masterpiece, “Roger & Me,” centering on the systematic obliteration of his hometown, Flint, Michigan, after the closure of its General Motors plant. Moore brilliantly injected humor into his exposé by juxtaposing the bleakness of the subject matter with his absurdist pursuit of an interview with GM’s CEO, Roger Smith, only to be faced with a barrage of stooges asking him to leave. Perhaps knowing that his microcosmic examination of middle class dissolution would be a bitter pill to swallow at feature-length, Moore utilized scathing satire as his weapon to combat corporate smarm, lacerating his targets with every impeccably placed quip and cut.

In contrast, Brizé’s film lives up to its title by taking us directly to the front lines of the wronged workers’ battle with company heads, foregrounding their plight with wall-to-wall urgency bereft of amusement. Cinematographer Eric Dumont lenses an opening street march with such disorientating handheld flourishes, you’d think that the activists were storming the beach at Normandy. As they did in “The Measure of a Man,” Brizé and Dumont keep the viewer engaged by allowing various stretches of the film to unfold in immersive long takes, with the camera darting back and forth during overlapping exchanges. Occasionally the back of an onlooker’s head will obscure the action, never more poetically than when Laurent is sandwiched by blurred figures on either side of the frame, expressing his newfound sense of alienation from his peers.

Though Lindon’s riveting performance is inarguably the film’s anchor, he is again accompanied by an exceptionally superb ensemble of nonprofessional actors, many of whom share the same names as their characters. Hauser may be the unreachable Roger Smith of this scenario, but the CEO who emerges as most reprehensible of all is Perrin’s CEO Censier (Guillaume Draux), a man incapable of containing his smug grin when declaring that the newly jobless employees can feel free to move elsewhere. Functioning as a referee of sorts during these tense encounters is the French president’s special adviser, Grosset (Jean Grosset), a blathering pest whose alleged efforts in service of the union amount to little more than hollow talk.

I especially liked the level-headedness of the union’s lawyer (Valérie Lamond), so skilled at arguing that the government’s obligation to Agen’s workers is a moral one, while stressing the employees’ refusal in being the “shareholder’s adjustment variable.” She also chimes in with a reasonable tone of voice whenever Laurent gets fired up. The tragic flaw of Laurent’s volatile temper repeatedly threatens to be his undoing, even as he urges his peers to maintain a cool composure, hushing their raucous chants and insisting that they fight cleverly. As tensions rise between Laurent’s loyal colleagues, particularly the pregnant Mélanie (Mélanie Rover), and those willing to give in to a hefty severance package, a few of the rebelling workers resort to the type of misogynistic name-calling characteristic our own president.

Laurent’s uncooperative activists admittedly have a point when they complain about his utter disinterest in how the media has been portraying their movement. Compressing the aspect ratio is to be expected when a film jumps to news coverage, yet Brizé takes a more nuanced approach to these segments, illuminating how the unused screen space mirrors the limited context provided by each perspective. The most shocking event is viewed on an iPhone, and its jarringly melodramatic punctation on the narrative is one of the film’s few missteps. More effective is the carnage brought about by enraged workers that a reporter narrates with play-by-play commentary, failing to detail the criminal acts that fueled this violence. In one of the film’s most harrowing sequences, riot shields are brandished by officers to push Laurent and his crowd of activists out of a lobby, herding them like cattle. It’s an apt metaphor for how the vulnerable are provoked into violence by literally being shoved out of public view until they snap.

Among the most chilling truths illustrated by Brizé and co-writer Olivier Gorce is how those driven purely by money will always remain more united than their adversaries because they aren’t divided by issues of empathy. The filmmaker’s depiction of infighting among union members could easily apply to America’s current Democratic party fractured by compromise and deceit. Though there’s a cathartic power to many of Lindon’s outbursts in the picture, his failure to restrain his rage during the much-anticipated meeting with Hauser is distressing in its lack of control. Of course, would any of us have fared better upon learning that the company is not lawfully bound to selling their plant, even with a potential buyer circling that could prove to be the union’s salvation? Like Censier, Hauser knows precisely what he’s doing when he laces his words with sarcasm, prompting the sort of response that will ultimately serve as exploitative fodder for news cameras.

“At War” is an exhausting film to watch in the best sense, venting our anger at the dehumanizing forces in society until we are left drained, contemplating our impending challenges with newfound clarity. The pension that secured the future of my father’s generation is no more, forcing the majority of Americans into a lifetime of hustling, racing the inexorable progression of “TIME,” as indelibly exclaimed in the Chambers Brothers’ metronome-like tune, “Time Has Come Today.” That song could’ve easily been selected as the anthem for this film, with its evocation of displaced souls crushed by the tumbling tide. To prevent his movie from devolving into two hours of shouting matches, Brizé mutes the dialogue at numerous moments, replacing it with Bertrand Blessing’s minimalist score, never more potently than when an older activist is removed from blocking the entrance to the plant, before being roughed up by officers in riot gear. The music’s rhythmic, industrial quality here suggests the gears of injustice as they churn away, indifferent to the lives they happen to be grinding up.