“Asylum” is well-titled, since everyone in it is more or less crazy, mostly more. It’s an overwrought Gothic melodrama that has a nice first act before it descends into shameless absurdity. To care about the story you would have to believe it, which you cannot, so there you are. Yet the movie is well made, and the actors courageously try to bring life into the preposterous story. Perhaps the original novel by Patrick McGrath held up better, or perhaps imagined images have a plausibility that gets lost when a movie makes them literal.

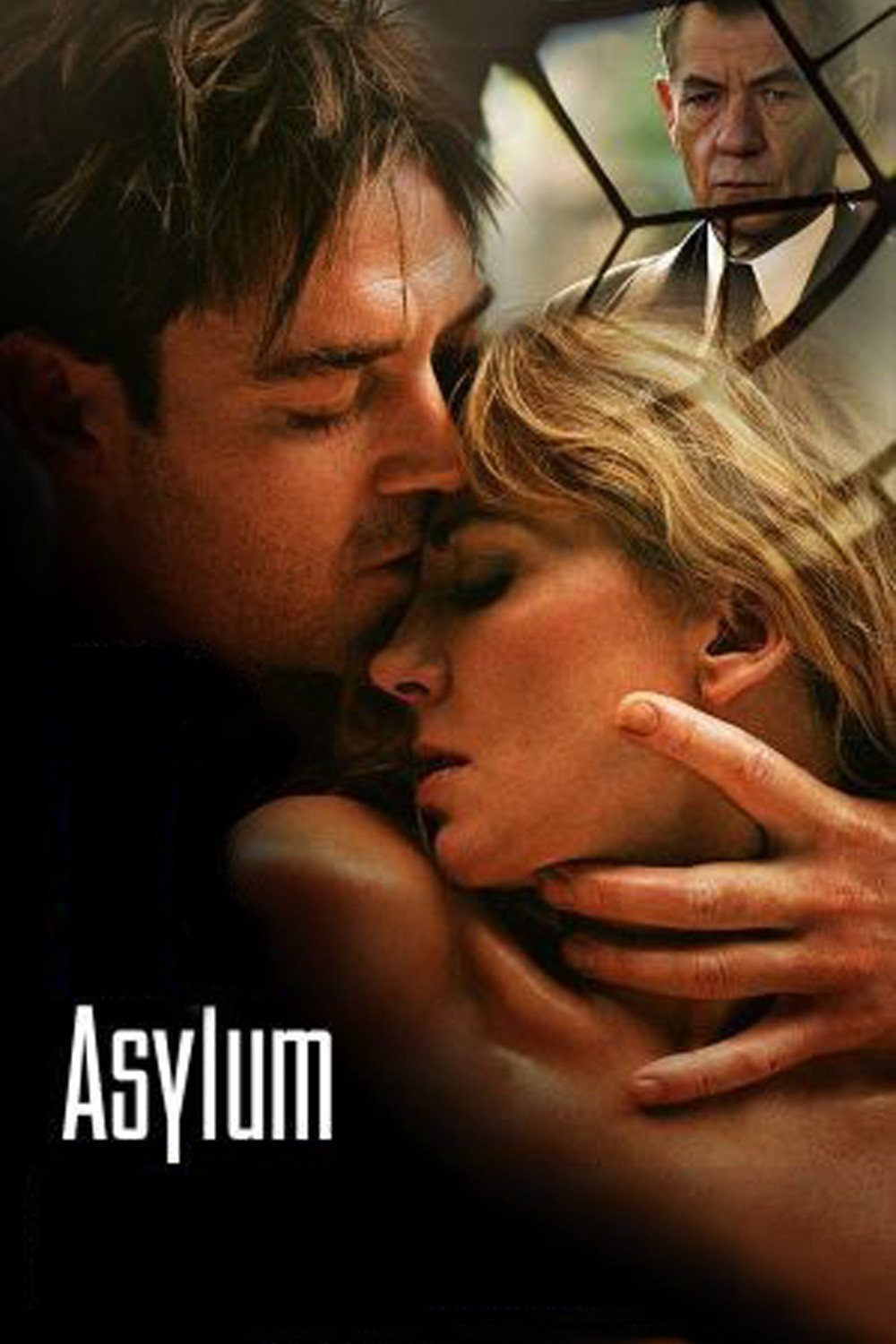

The story is set circa 1960 in a vast old asylum built in the Victorian era — one of those buildings looking like an architectural shriek. Max Raphael (Hugh Bonneville) has arrived to become the new superintendent; he brings his wife Stella (Natasha Richardson) and their son Charlie (Gus Lewis). All is not well in this family, but then nothing is right in the asylum, where the long-serving Peter Cleave (Ian McKellen) resents being passed over for Max’s job. He’s expected to serve as Max’s second-in-command, leading to acid one-liners that McKellan delivers like dagger thrusts:

Max: “May I remind you that I am your superior?”

Peter: “In what sense?”

Max and Stella seem separated by a vast emotional gulf. Charlie is not much loved by his parents. He finds a friend in one of the patients, Edgar (Marton Csokas), who becomes his buddy and sort of a father-figure, which would be heartening if Edgar had not been declared insane after murdering his wife, decapitating her, and so on and so forth.

Edgar undertakes to rebuild a gardener’s shed that Stella wants to make use of. Soon she is making use of it with Edgar. There is this to be said for Natasha Richardson: Required to play an asylum-keeper’s wife who has sudden, frequent and heedless sex with an inmate, she doesn’t leave a heed standing.

Edgar’s diagnosis is “severe personality disorder with features of morbid jealousy.” With admirable economy, the movie eventually applies this diagnosis to just about everyone in it except little Charlie, who is way too trusting, and not just of Edgar. There are lots of scenes involving British twits who are well-dressed but with subtly disturbing details about their haberdashery and styles of smoking. They sit or stand across desks from one another and exchange technical jargon that translates as, “I hate you and your kind.” Meanwhile the cinematographer, Giles Nuttgens, makes the asylum into a place so large, gloomy and forboding that we suspect maybe “Eyes With No Face” is being filmed elsewhere on the premises.

If I’m spinning my wheels, it’s because we’ve arrived (already) at a point in the plot where major developments start to tumble over one another in their eagerness to bewilder us. In my notes I find many entries beginning with such words as:

Yes, but … Why would … Surely they … Yet he … How could …

And then several one-word entries followed by too many exclamation points, such as:

Drowns!!!

But I do not want to spoil these developments, and so will not reveal who drowns, except to say it’s not every movie that reminds you of “Leave Her to Heaven.” There is also a question, some distance into the film, of the plausibility of certain living arrangements. Also of their wisdom, of course, but wisdom at this point has been left so far behind it’s churlish to double back for it.

The director, David Mackenzie, made “Young Adam,” also the story of a married woman attracted by a young and possibly dangerous man. The screenplay is by Patrick Marber, who wrote “Closer,” a movie about four-way sexual infidelity involving characters who deserved each other. Certainly the characters in “Asylum” richly earn their fates, and by the end we are forced to reflect that although they are indeed mad, at least the villain is acting reasonably under the circumstances.