The CCTV footage from Kuala Lumpur International Airport on February 13, 2017 shows two teenage girls, moving separately, coming up the escalator, strolling past the shops, seemingly without a care in the world. One has long hair. The other has a short bob, and wears a white T-shirt with “LOL” visible on the front. The girls converge on a short pudgy man, and attack him from behind, although the footage is so pixelated it’s hard to tell what has happened. The girls then walk away, separately, holding their hands in the air, visit the restrooms, and then leave the airport, taking separate cabs back into the city. The man they attacked turned out to be Kim Jong-nam, half-brother to Kim Jong-un, “dear leader” of North Korea. The girls’ hands were slathered with the lethal nerve agent VX, which works so rapidly there’s little to no time for treatment: Kim Jong-nam is seen on the CCTV footage, already limping slightly as the VX takes effect, accompanied by airport security. He would be dead within 20 minutes. The two girls, the Vietnamese Doan Thi Huong, and the Indonesian Siti Aisyah, were arrested a couple days later. They both claimed to have been participating in a YouTube prank show. They thought it was body lotion on their hands. They had no idea the man they attacked was anyone important. One of them had no idea who Kim Jong-nam even was. A news anchor asked: “Were the women trained assassins or innocent pawns of North Korean agents?”

Amidst the frenzy of international press, this would be the crucial question, not only for the girls’ beleaguered defense attorneys, but for everyone watching. The details are almost too far-fetched to believe. It feels like a meme come to life: Spreading a deadly nerve agent in some poor unsuspecting guy’s eyes just for the lulz. LOL! Could the two girls have really been that naive? Could they really have had no idea what they were doing? Could this brazen in-broad-daylight attack really have been part of a long con organized by North Korea to get rid of the potential “rival” for Kim Jong-un’s “throne”? Or were these two apolitical girls—with no known connection to North Korea—in actuality cold-blooded assassins?

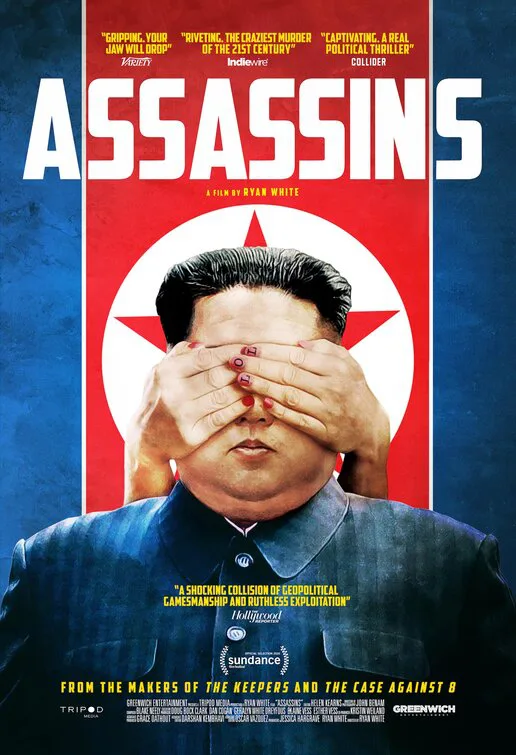

There is so much news in the world it’s impossible to absorb it all. Documentaries and podcasts often fill that gap. This is what Ryan White’s documentary “Assassins” does, and he does it with straightforward clarity, an admirable choice particularly considering the outlandish nature of some of what went on. You’d think the tendency to “play up” the outrageous-ness would be irresistible, that it would be fun to “riff” on the more unbelievable aspects, via visual flourishes or pointedly ironic needle drops. The jokes practically write themselves. But White resists. In his mostly excellent documentary “Ask Dr. Ruth,” White “spiced up” the narrative with animated sequences, and an actress-voiced voiceover: these did little to illuminate the subject and felt unnecessary. Here, White plays it straight, and deftly untangles the different webs of meaning and implication, political, social and otherwise, to draw us into Siti and Doan’s worlds, to understand how the girls were tricked and used as pawns in a deadly North Korean family feud.

Both Siti and Doan came from humble families, naive country girls, caught up in forces beyond their understanding in the “big city.” Doan had artistic aspirations. She wanted to be an actress. She participated in the trend of “prank videos,” modeled after the Jackass trilogy (although not nearly as creative). The work was intermittent, but at least it wasn’t dirty or back-breaking. Siti’s backstory is a bit more grim: she left her village and moved to Jakarta where she found work in a clothing factory. She married her boss, gave birth to a child at 17, whom she then lost to her ex in the eventual divorce. She moved to Kuala Lumpur and drifted into sex work. When a taxi driver named John (one of the many mysterious figures who enter this story) tells Siti about a potential job participating in prank videos through a Japanese company, Siti jumped at the chance. It was better than sex work. The girls were managed by another mysterious person named “Mr. Y,” who made sure the girls rehearsed the pranks beforehand, coaching them on the effects necessary. “Everyone has their own roles to play,” Mr. Y texts Doan, a chilling message if you think of him not as a Japanese video-producer but as a North Korean secret agent.

White knows we need guides for all of this, and he has chosen well. Two journalists interviewed for “Assassins” walk us—step by step—through this absurd and, at times, horrifying chain of events. There’s Hadi Azmi, a Malaysian journalist who covered the story from start to finish, up to and including the eventual 2019 trial. (No spoiler to say that both girls were eventually released.) Azmi is an excellent guide, explaining the limits on the press in Malaysia’s state-owned media, and how this came into play during the search for truth. Both girls faced the death penalty. There was powerful pressure to find them guilty, to not look further into the improbabilities of the case as it stood. Azmi says, with a wry grin, “Malaysia is one of those weird countries who actually has diplomatic relations with North Korea.” Another excellent guide is Anna Fifield, the Washington Post’s bureau chief in Beijing, who has been covering North Korea since 2004. Using a family tree graphic, she lays out the “Mount Paektu bloodline” of North Korea’s dynasty, showing why Kim Jong-un had such a vested interest in getting rid of his older brother, who—not incidentally—was also the favored son of their father, the doted-on first-born.

The question of “guilt” was cut-and-dried: you can see the attack on the footage. They did it. But are they guilty under the circumstances? Fifield says, “In many ways, this is the perfect crime.” It really is. And North Korea almost got away with it, and would have gotten away with it, if it weren’t for skeptical people like Azmi, who smelled a rat early on, and for people like the girls’ legal teams, whom White eventually loops into the story. We’re witness to their struggles to build a case, going through the 1000s of text messages from the girls’ phones (not one word about North Korea in any of them, damning evidence for the prosecution), the conferences (private and public), the lawyers’ challenges in presenting the material to an unfriendly court.

There are many tantalizing “roads not taken” in “Assassins.” White keeps the story focused on the girls. He plays audio recordings of them being interviewed from prison, where they sound dazed and disoriented. The geopolitical implications are clear, although this is not “Assassins”‘ primary concern. With his brother out of the way, Kim Jong-un has nothing to fear for the foreseeable future. After Kim Jong-nam’s murder, a bombshell drops that he had been a high-level CIA asset, and was holding a suitcase full of American cash. Considering all we just saw in the film, it’s even more sickening then to listen to President Trump’s comments upon hearing the news, where he sided with North Korea over America’s intelligence community.

Siti Aisyah and Doan Thi Huong are free. But Kim Jong-un still won. The victory here is only partial.

Now available in virtual cinemas.