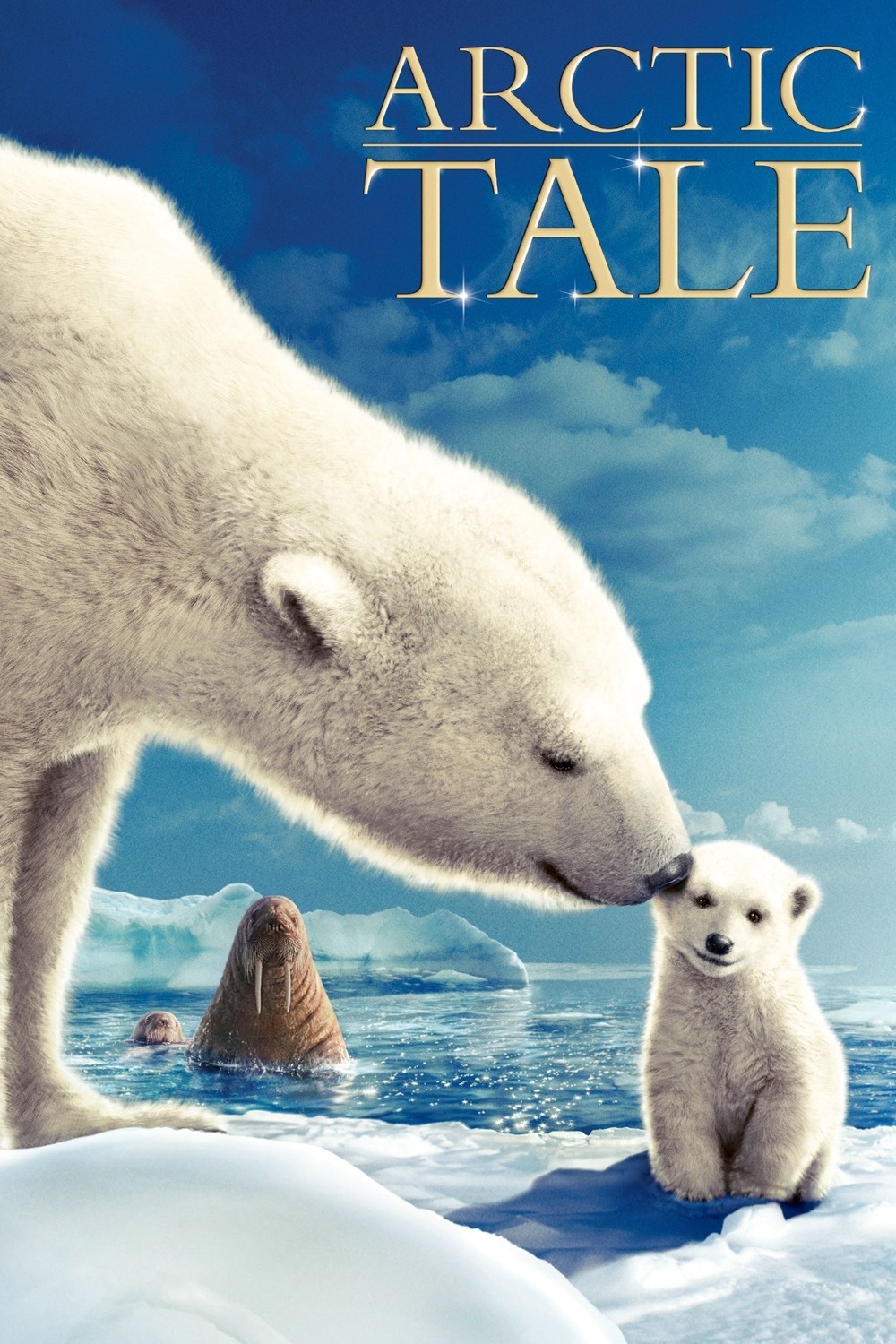

“Arctic Tale” journeys to one of the most difficult places on earth for animals to make a living, and shows it growing even more unfriendly. The documentary studies polar bears and walruses in the Arctic, as global warming raises temperatures and changes the way they have done business since time immemorial.

Much of the footage is astonishing, considering that it was obtained at frigid temperatures, sometimes underwater, and usually within attacking distance of large and dangerous mammals. We follow two emblematic characters, Nanu, a newborn polar bear cub, and Seela, a newborn walrus. The infants venture out into their new world of blinding white and merciless cold, and learn to swim or climb onto solid footing, as the case may be. They also get lessons from their parents on stalking prey, defending themselves against predators, and presumably keeping one eye open while asleep.

The animals are composites of several different individuals, created in the editing room from footage shot over a period of 10 years, but the editing is so seamless that the illusion holds up. The purpose of the film, made by a team headed by the married couple of director Sarah Robertson and cinematographer Adam Ravetch, is not to enforce scholarly accuracy but to create a fable of birth, life and death at the edge of the world.

It is said that the landmark documentary “March of the Penguins” began life in France with a cute soundtrack on which the penguins voiced their thoughts. The magnificence of that film is explained in large part to Morgan Freeman’s objective narration, which was content to describe a year in the lives of the penguins; the facts were so astonishing that no embroidery was necessary.

“Arctic Tale,” however, chooses the opposite approach. Queen Latifah narrates a story in which the large and fearsome beasts are personalized almost like cartoon characters. And the soundtrack reinforces that impression with song: As dozens of walruses huddle together on an ice floe, for example, we hear “We Are Family” and mighty blasts of walrus flatulence.

They might also have been singing “we are appearing in a family film.” The movie might be enthralling to younger viewers, and the images have undeniable power for everyone. The dilemma the movie sidesteps is that being a polar bear or a walrus is a violent undertaking. In a land without vegetation, evolution has provided animals that survive by eating each other. In one blood-curdling scene, Nanu’s mother cautiously shepherds her cubs away from a male polar bear that would, yes, like to eat them. The walrus with her baby is automatically paired (it seems) with another female walrus, an “auntie,” who volunteers to help protect the little family. This is all the more unselfish considering what happens to the auntie.

The film does not linger on scenes of killing or eating, preferring to make it clear that such events, and other tragedies, are happening not far offscreen. The eyes of little audience members are spared the gory details. But the comfy view of Arctic life, opening with those two little bear cubs romping in the snow and snuggling under mom for a snack, quickly descends into a struggle for survival.

It’s hard enough for them to live in such an icy world, but harder still when the ice melts. When ice grows scarce, so will polar bears and walruses, because although both species are accomplished swimmers, they are mammals and have to breathe and need to crawl up on ice floes. Queen Latifah’s narration, co-authored by Al Gore’s daughter Kristin, makes it clear that global warming is to blame. We see Nanu walking gingerly across ice that is alarmingly slushy, and we can only speculate about how that makes her feel.

The movie gives some attention to other northern ice forms, including jellyfish, birds and foxes who trail behind polar bears to eat the remains of their kills. We see no humans, not even the Inuit who assisted the filmmakers.

In the end, I’m conflicted about the film. As an accessible family film, it delivers the goods. But it lives in the shadow of “March of the Penguins.” Despite its sad scenes, it sentimentalizes. It attributes human emotions and motivations to its central animals. Its music instructs us how to feel. And the narration and overall approach get in the way of the visual material.