“Apt Pupil” uses the horrors of the Holocaust as an atmospheric backdrop to the more conventional horror devices of a Stephen King story. It’s not a pretty sight. By the end of the film, as a death camp survivor is quoting John Donne’s poem about how no man is an island, we’re wondering what island the filmmakers were inhabiting, as they assembled this uneasy hybrid of the sacred and the profane.

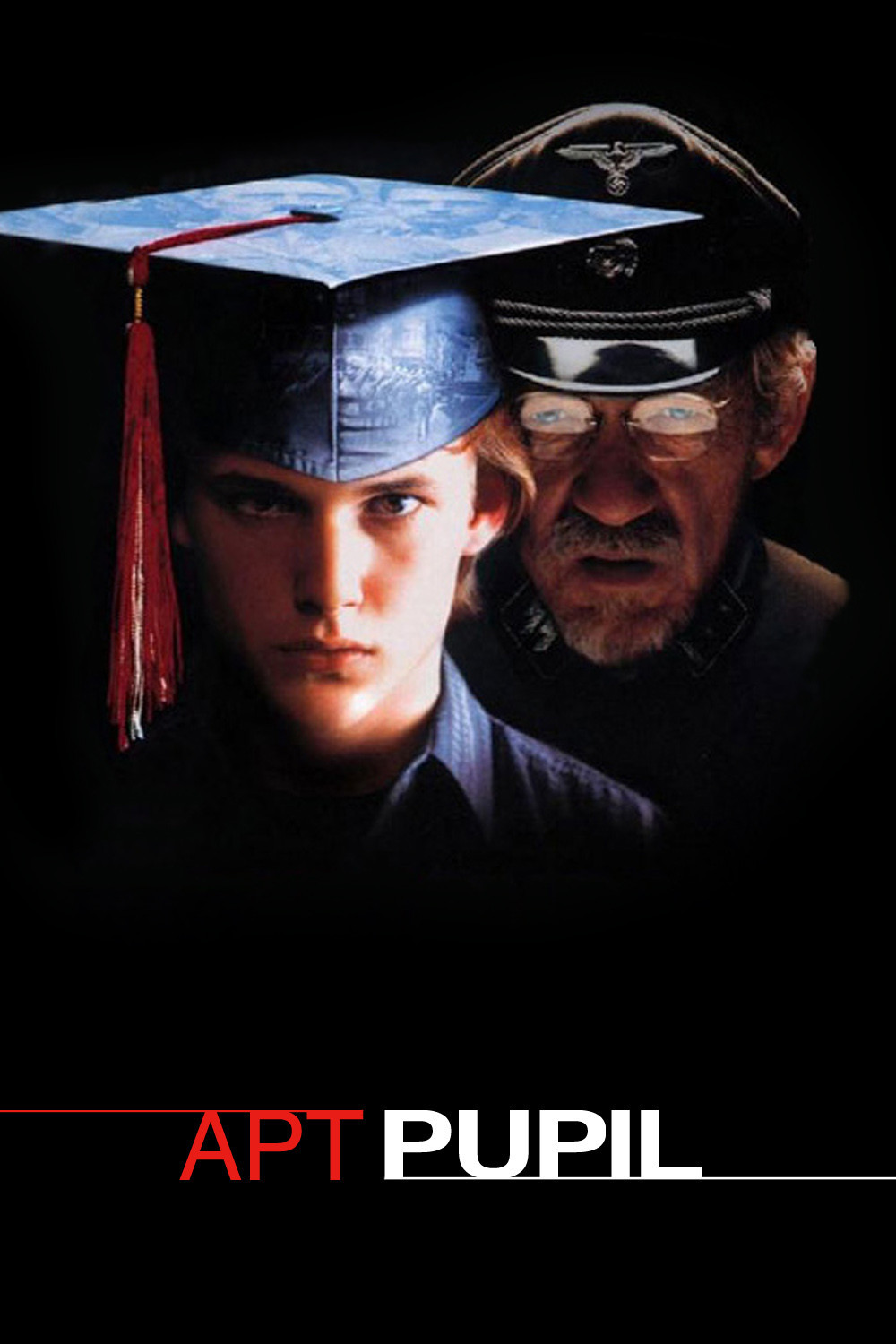

The movie is well made by Bryan Singer (“The Usual Suspects“) and well acted, especially by Ian McKellen as Kurt Dussander, a Nazi war criminal who has been hiding in American for years. The theme is intriguing: A teenager discovers the old man’s real identity, and blackmails him into telling stories about his wartime experiences. But when bodies are buried in cellars and cats are thrown into lighted ovens, the film reveals itself as unworthy of its subject matter.

Bran Renfro is the co-star, as Todd Bowen, a bright high school kid who after a week’s study of the Holocaust, notices a resemblance between a Nazi criminal and the old man down the street. Using Internet databases and dusting the old guy’s mailbox for fingerprints, Todd determines that this is indeed a wanted man and confronts him with a strange demand: “I want to hear all about it. The stories. Everything they were afraid to tell us in school. No one can tell it better than you.” The old man is outraged, but trapped. He shares his memories. And the film, to its shame, allows him to linger on details: “Although the gas came from the nozzles at the top, still they tried to climb. And climbing, they died in a mountain of themselves.” Soon the boy undergoes a transformation into a bit of a Nazi himself. He brings the old man a Nazi uniform, makes him put it on and orders him to march around the kitchen: “Attention! March! Face right!” When the old man protests, young Todd barks: “What you’ve suffered with me is nothing compared to what the Israelis would do to you. Now move!” The movie at least doesn’t present the old man as repentant. Indeed, under the urging of the boy, he seems to regress to his earlier state, and there is the particularly nasty scene where he attempts to gas a neighbor’s cat in his oven. (Does he succeed? The movie’s shifty editing seems to permit two conclusions.) This scene is paired with another in which an injured bird is killed by a bouncing basketball.

Is there some kind of social message here? Some overarching purpose? If there were, then the material itself would not automatically be offensive. But the later scenes in the movie seem more–not less–exploitative. After the old Nazi tries to kill a spying bum and push him down the basement stairs, he calls on the kid to finish the job: “Now we see what you are made of!” We even get the tired cliche where a body seems to be dead and then rears up, alive. And of course victims being hit over the head with shovels.

All of this plays against a subplot where the kid tells lies at school, and even blackmails the old Nazi into posing as his grandfather at a counseling session. And at the end, after it is far too late for the film to change its nature, there is an attempt at moral balancing, including the poetry-quoting patient in the next hospital bed. That John Donne poem, about how no man is an island, about how we are all part of the larger humanity, ends with words that might profitably be considered by the filmmakers: “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”