OK, admit it: which one of you introduced actor-turned-filmmaker Tim Blake Nelson to nihilism? Nelson (“Leaves of Grass,” “Eye of God“) is smart enough to independently discover works like “Ex Nihil” and “The Conspiracy Against the Human Race,” questionable philosophical tracts that recently came to a wider attention once “True Detective” Nic Pizzollato cited the latter book as a source of inspiration for his signature drama’s first season. But I’d prefer to believe that “Anesthesia,” the fifth film to be written and directed by Nelson, wasn’t originally Nelson’s idea. This will hopefully make sense later.

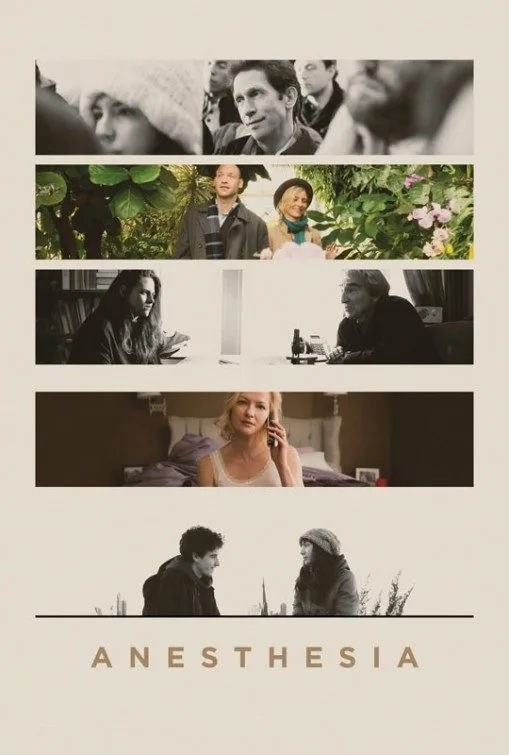

“Anesthesia” is equal parts civics lesson and ideological confession. It’s like if “Pay It Forward” had an exceedingly glum sequel that questions whether or not human beings know that they cannot affect positive change in each other’s lives, and therefore distract ourselves from life’s meaninglessness with everything from drug abuse to child-rearing. An all-star cast of actors, including Kristen Stewart, Gretchen Mol, Glenn Close, Corey Stoll and Michael K. Williams, band together to breathe dramatic life into Nelson’s “echo chamber,” to paraphrase one of his more astute lines of dialogue.

Several fantastically contrived subplots, including a family struggling with news that mother Jill (Jessica Hecht) may have malignant cancer and a high-powered lawyer (Williams) who tries to help his childhood best friend (K. Todd Freeman) to quit his drug habit, suggest that people are all connected, either by their mutual sense of responsibility and/or apathy. Philosophy professor Walter Zarrow (Sam Waterston) gives voice to many of Nelson’s concerns in lectures, and has private conversations with students like self-harming depressive Sophie (Stewart). Zarrow asks his students to consider if we can find meaning beyond ourselves, if the urge to procreate is not mindless, after a fashion, and if we are simply perpetuating our beliefs without interrogating them. In other words: if we examined our motives, would we find that we’re predisposed to futilely exist, work away at our respective jobs, and then pass on our unproductive values to our children? Does anything have a point, and if not, why not just give up?

Nelson’s characters are defined almost exclusively by their concerns and their patterns of behavior, making Waterston’s character the most attractive since he gets all the good speeches. This makes it especially hard to take “Anesthesia” seriously whenever its various stories break down into a series of monologues. Poor Kristen Stewart does a fantastic job with lousy material when Sophie confesses that she burns her forearms with a curling iron to confirm that she exists. There is real pain in Sophie’s biggest rant, and it doesn’t just come from Stewart’s performance, but that sympathetic hurt is considerably dulled by the fact that we don’t really know who Sophie is beyond one pointless cafeteria altercation, and a couple of theoretical conversations with Zarrow. Large parts of “Anesthesia” consequently feel like strangers’ confessions.

This is a movie about empathy, after all, but human emotions that have been reduced to abstract consideration. Joe’s struggle with addiction is probably the best part of “Anesthesia” because Nelson devotes time to representing Joe’s anger. He curses frantically as he struggles to break out of a hospital gurney he’s been strapped into against his will. And he half-prays, half-curses Jeffrey when he doesn’t pick up his “goddamn phone.” This pain feels very real even though it’s also essentially a type of character. Joe contrasts with Zarrow’s optimism, and represents one end of an emotional spectrum that multiple characters, including young pothead Hal (Ben Konigsberg), gravitate towards.

The film often leads the viewer around in circles (as Zarrow fearfully admits during one of his later speeches); it’s a weirdly over-determined cri di coeur that feels simultaneously over- and under-done. Still, I want to recommend Nelson’s film in spite of how misconceived it is simply because it asks interesting questions, albeit in some of the most banal ways imaginable. That recommendation seems to be the only way out of Nelson’s echo chamber: invite people in, and make the conversation a dialogue. I’m very curious to read people’s thoughts on the film. So if you see “Anesthesia,” please tell me what you think. And in the meantime: if you turned Tim Blake Nelson on to nihilism, you can tell me that, too. I won’t judge, promise.