“The only distinction between Bush and Gore is the velocity with which their knees hit the floor when big corporations knock on the door.” — Ralph Nader, repeating one of his talking points in the Los Angeles Times, June 27, 2000

“I think Nader is a Leninist. He thinks things have to get worse before they get better.” — Media critic Eric Alterman in “An Unreasonable Man”

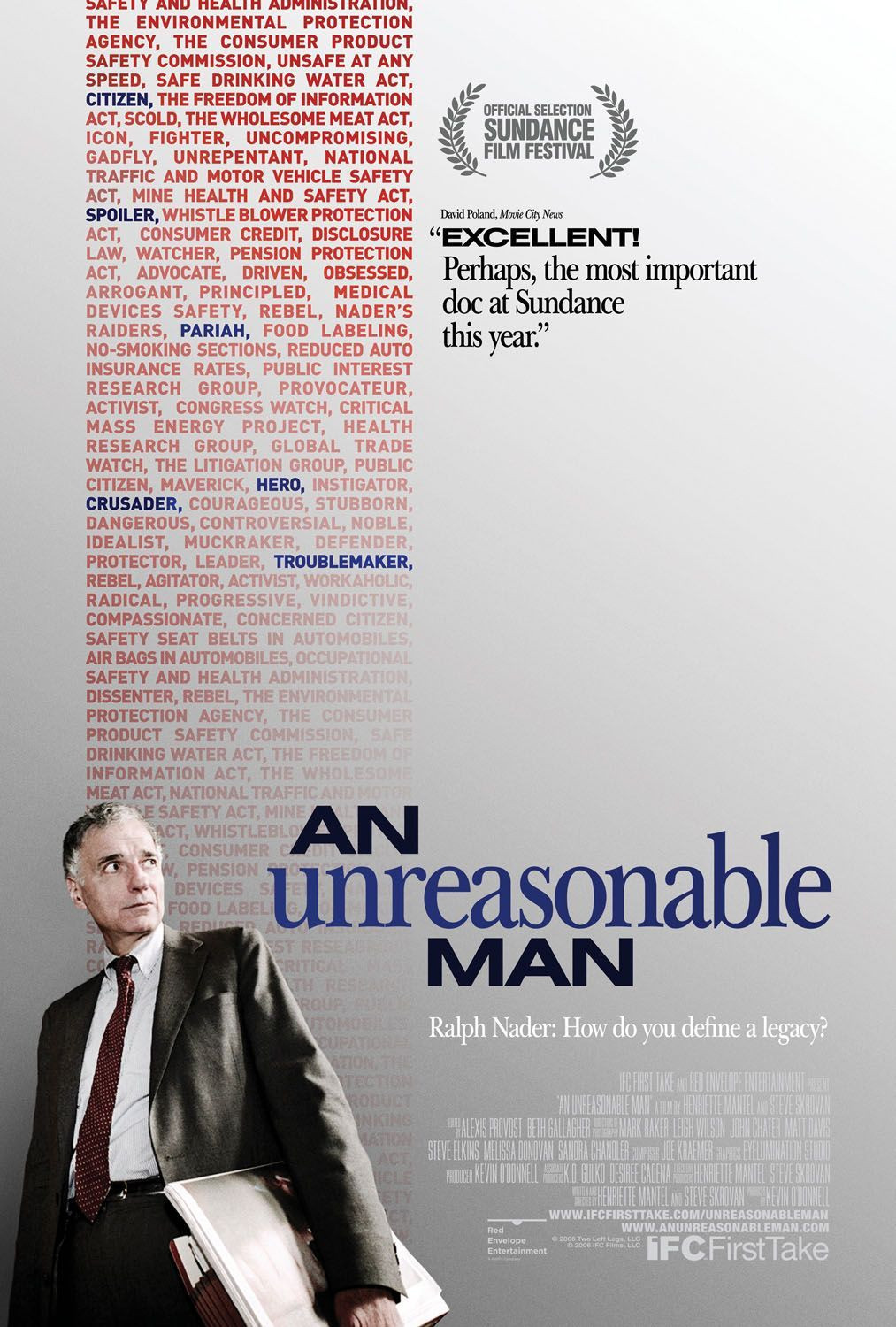

If the collapse of presidential candidate Ralph Nader’s reputation has been a “tragedy” of Shakespearean dimensions, as his friend Phil Donohue says near the beginning of “An Unreasonable Man,” then it’s reasonable to ask: What is the nature of that tragedy?

Is it that Nader, a consumer advocate who once stubbornly fought for progressive reforms that saved lives and held corporations and government accountable for their actions, has been treated as a pariah since the 2000 presidential election? Or is it that, having entered partisan politics, Nader has just as stubbornly placed the importance of his symbolic candidacy ahead of the real-world reforms he once struggled to bring about?

This eminently sympathetic documentary, made by Henriette Mantel and Steve Skrovan, a pair of comics who are friends of Nader’s, tilts strongly toward the former point of view while still paying lip service to the latter. It comes front-loaded with strong condemnations of the former Public Citizen No. 1 from prominent critics and ex-colleagues, including Columbia University’s Todd Gitlin and former President Jimmy Carter, who say Nader has self-destructively sold out his principles. By adopting campaign rhetoric insisting there were few significant differences between the Democratic and Republican candidates, and thereby helping to install George W. Bush in the presidency, they say, Nader has discouraged third-party activism (look at the practical results!) and further enabled the institutional deregulation that has dismantled many of the important protections Nader fought to implement earlier in his career.

“An Unreasonable Man” fudges questions about Nader’s motives, and the consequences of his behavior, in several respects. It disputes what he said about the differences between the parties but never quotes from what he’s on the record saying at the time. By the end of the film, when the music swells and Nader delivers a stump speech into the camera (“There’ll never be a hill that you don’t have to climb when it comes to injustice in this world … “), it’s obvious what this movie really is: a two-hour commercial for a possible Nader 2008 presidential campaign. In 1992, Bill Clinton claimed to be the “Man from Hope.” In 2007, Nader paints himself as an ideologically pure crusader in “An Unreasonable Man.”

But, you may ask, why should anyone care about who Nader is, or once was? The movie endeavors, selectively, to address such questions. And the trouble with it, the dishonest thing about it, is not that it has a pro-Nader spin — docs have every right, maybe even a duty, to make arguments and advocate points of view. Because “An Unreasonable Man” is pitched as a primer for people who don’t know much about Nader in the first place, they may perceive it as a both a call to action (which it is) and a “fair and balanced” portrait of Nader’s career (which it isn’t), simply because it presents some opposing views. The movie is lively and informative, but (in ways the old Nader might have appreciated) it made me feel like arguing with it. Frustratingly, the film avoids as many issues as it raises.

Why, for example, didn’t Nader run on the Green Party ticket in 2004? The movie doesn’t say. If Nader entered the 2000 race with the goal of attracting 5 percent of the popular vote (he only got 2.7, but the movie doesn’t tell you that), and then won only 0.4 percent in 2004 (less than Gore’s popular vote victory in the previous election, but the movie doesn’t tell you that either), what does that say about the support for, and effectiveness of, his candidacy? Who does he represent, and who is listening to what he’s saying? If his aim is to change the system from within, is there some deficiency in the message, or there a problem with the messenger? If he’s been abandoned by so many of his allies and blackballed by the media, might not someone else make for a more productive and persuasive spokesperson at this point? Or does he simply repeat the same self-justifying behavior, with diminishing returns, expecting a different result (Einstein’s definition of insanity)?

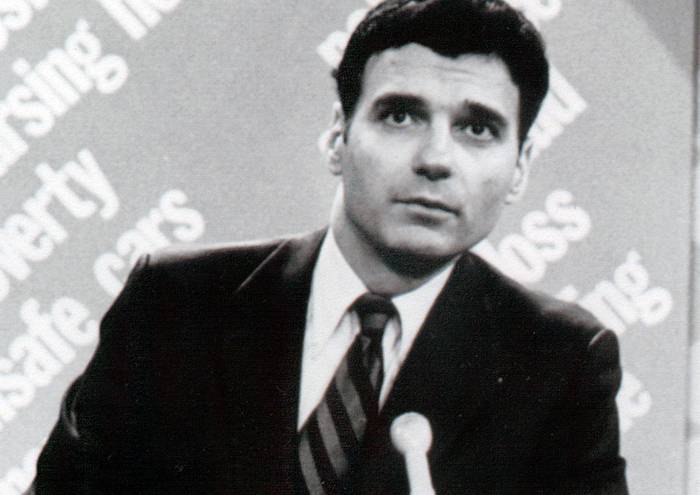

“An Unreasonable Man” offers a brisk overview of Nader’s early days as he took on the American auto industry, noting in a 1959 article in The Nation (“The Safe Car You Can’t Buy”): “It is clear Detroit today is designing automobiles for style, cost, performance and calculated obsolescence, but not — despite the 5,000,000 reported accidents, nearly 40,000 fatalities, 110,000 permanent disabilities and 1,500,000 injuries yearly — for safety.” At the time, car owners had little idea so many of these accidents, deaths and injuries were preventable with simple safety measures like seat belts, which the manufacturers were keeping off the market.

As Nader articulated in his best-selling 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile, the free market (like democracy itself) can’t function freely unless citizens have the facts they need to make informed decisions: “A great problem of contemporary life is how to control the power of economic interests which ignore the harmful effects of their applied science and technology.”

Nader became a valuable brand name for consumer rights, and citizen’s rights, fighting for regulations to protect consumers and open up government. He put his name and resources behind scores of causes, from food and drug labeling to environmental protections to the Freedom of Information Act — many of which have been conspicuously defanged by the Bush administration.

Nader says: “I don’t care about my personal legacy. I care about how much justice is advanced in America and our world day after day.” If that’s true, some would suggest — though not the makers of this film — that the man needs to take a good look around him, followed by a long, hard look in the mirror.

Note: Director Steve Skrovan will appear Saturday at the Music Box, and there will be a live video conference Q&A with Ralph Nader after the movie’s 7 p.m. screening Saturday.