With a 54 kilometer border shared with Russia, the city of Manzhouli in China is in the country’s most northern corner. It is the busiest land port of entry in the country. Railways pass through the city, a series of arteries and tributaries, allowing for trade and movement of goods. This economic lifeblood cycles endlessly along the same tracks as trains lumber ahead constantly on their predestined path. In Hu Bo’s epic first and final feature film, “An Elephant Sitting Still,” there is a mythical elephant who lives in Manzhouli, sitting still, indifferent to the cruelty of the world.

Hu Bo attended the Beijing Film Academy and graduated with a B.F.A. in directing. He made a couple of short films and was also a novelist, publishing two books “Huge Crack” and “Bullfrog” in 2017. Shortly after completing his short film “Man in the Well” and “An Elephant Sitting Still,” Hu Bo took his own life. He was just 28 years old.

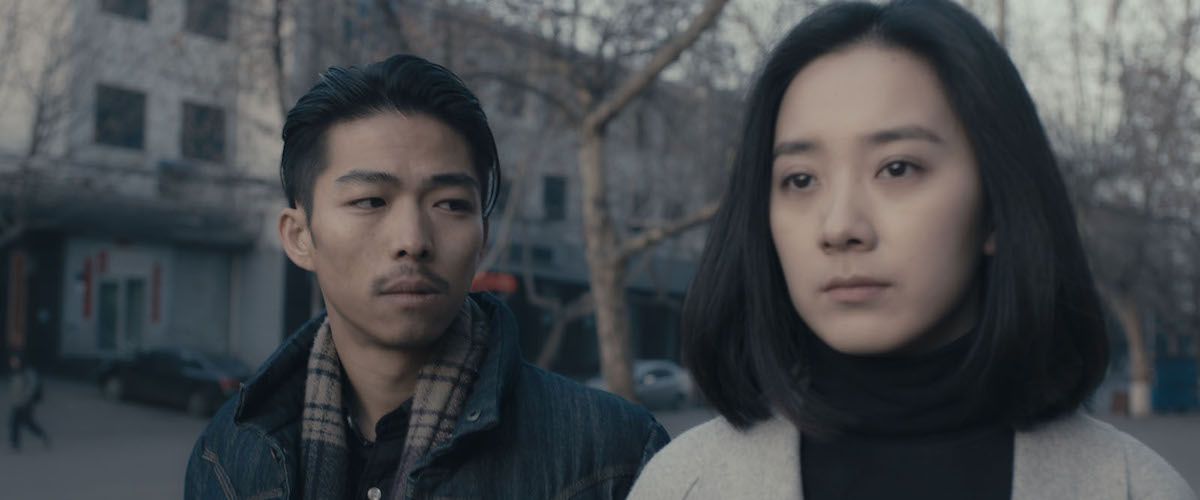

“An Elephant Sitting Still” runs at 230 minutes and is overwhelmingly grey. The sun rarely peeks out from beyond the clouds and the four central characters are burdened with a deeply seated hopelessness. Long takes are filled with aching silences, as captured by an uncomfortably intimate camera. In a convergence of destinies, the characters are drawn to the city of Manzhouli and the influence of a mythical elephant.

If cinema’s central identity is tied to capturing time, “An Elephant Sitting Still” captures the drudgery of time once its spiritual significance has been lost. Taking place within a single 24-hour period, the character’s lives are filled with incident. There are sexual affairs, violent altercations and tragic deaths, but rather than being the impetus for change, these actions feel part of an unrelenting cycle of violence. The preference of long takes does not translate into peaceful filmmaking, but rather kinetic nervousness, as Hu Bo abandons static set-ups in favor of a mobile and frenetic camera. The mise-en-scene reflects characters and environments caught in a perpetual loop with little hope for escape.

The camera often comes close to the characters, suggesting a lack of bodily autonomy and freedom, acting like an invasive surveillance. It feels like a detective searching for answers to an impossible puzzle. Who are these people? What are their dreams and aspirations? How do they find the reason to keep on living? As the camera usually adopts a low-angle perspective, there is a strange reverence attached to these images as well. Even with a sometimes aloof and cold performance style, the characters are imbued with love and adoration by a camera that feels invested in shedding light on their struggle and endurance.

The constant movement of trains serves as a crucial backdrop within the film. The railways rather than being a path of freedom become bogged down with bureaucratic limitations, unreliable schedules and frequent scams. The promise that Manzhouli offers as an important port of entry does not translate to real change or transformation even if it remains largely inaccessible to the film’s desperate characters. The crackling uncertainty of economic instability results in broken families, homes and bodies. All the characters seem to live lives they would never have chosen if given any options. Just like a train’s path is pre-written and inescapable, straying from pre-destiny feels cataclysmic rather than liberating.

But the film is not completely hopeless. While circumstances are claustrophobic and stifling, Bo’s movie seems to balance that with strange and surreal impulses of the heart. The characters are beaten down by life but they are still capable of love and connection. As “An Elephant Sitting Still” runs towards its epic confrontational climax, a sense of doom is measured against the growing influence of love.

Love becomes a bit of a double-edged sword, however, as it is often presented as a sacrifice above all. Love is one-sided, as is the case with a young student having an affair with her teacher. For a small time gangster, love means giving yourself over to people and systems that will almost inevitably betray you. Love means obligation, which often means tethering yourself to people who have long been broken by mistreatment and inequality and who no longer have the capacity to return it. Love does not overcome all within a broken social system: love leads to shame, betrayal and unhappiness.

Yet, love and beauty remain a constant source of minute, if not fleeting, pleasure. It is not a cure-all in the way it would be in a Disney princess fantasy, but it is enough to sustain existence in spite of its high risk and low reward ratio. The film is not down on love as much as it is realistic in its portrayal of it within a system of inequality and oppression. It is impossible to watch its final act and not feel the warming sensation that maybe tomorrow will be different, bringing change and offering beauty, love or hope.

By the movie’s last shot, the camera has stepped outside of the intimate closeness of its characters. They can finally breathe, allowing for a spiritually transcendent ending, one of the greatest in contemporary film history. Suddenly there is scope, perspective, and spiritual silence. The pace remains slack but time has regained meaning outside of suffering, at least for a few hours along an unfamiliar path.