“A Time for Drunken Horses” supplies faces to go with news stories about the Kurdish peoples of Iran, Iraq and Turkey, people whose lands to this day are protected against Saddam Hussein’s force by a no-fly zone enforced by the United States. Why Hussein or anyone else would feel threatened by these isolated and desperate ly poor people is an enigma, but the movie is not about politics. It is about survival.

In dialogue over some of the opening scenes, we meet three young Iranian Kurdish children: Ameneh, a teenage girl; Ayoub, her brother, who is about 12, and Madi, their 15-year-old brother, a dwarf whose fiercely observant face surmounts a tiny and twisted body. They live with their father, who, Ameneh matter-of-factly reports, works as a smuggler, taking goods by mule into Iraq, where they fetch a better price.

The children work every day in a nearby town. They are child labor, put to work wrapping glasses for export, or staggering under heavy loads they carry around the marketplace. Their hand-to-mouth existence undercuts easy Western theories about child labor; they work to eat, and will be dead if they don’t.

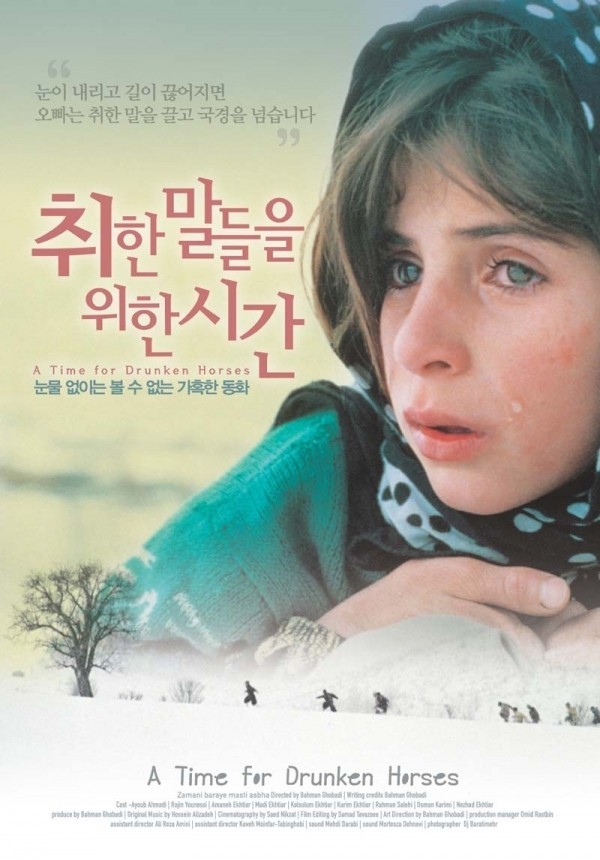

We see them in the back of a truck returning to their village, and there is a shot that emotionally charges the whole film. Ayoub and Ameneh sit close together, both helping to hold little Madi. Ayoub caresses the hair of the little creature, and Ameneh gently kisses him.

They love their crippled brother, who never speaks throughout the film, who must have regular injections of medicine, who needs an operation, who will probably die within the year even if he gets the operation.

The truck is stopped by guards and impounded. The three siblings struggle together through the snow, separated now from their father. Their existence is more desperate than ever. They become involved with mule-trains that smuggle truck tires over the mountains to Iraq. The high mountain passes are so cold that the mules are given water laced with alcohol, to keep them going–thus the title. Ameneh agrees to marry into a Kurdish family from across the mountains, if they will pay for Madi’s operation. What happens then I will not reveal.

The movie is brief, spare and heartbreaking. It won the Camera d’Or, for best first film, at Cannes this year. Some find it boring, but I suspect they are lacking in empathy (one Internet critic magnanimously concedes that the movie “might have contained some appeal” if “my life were pathetic enough”). “A Time for Drunken Horses” has the same kind of conviction as movies like “The Bicycle Thief,” “Salaam Bombay” and “Pixote“–movies that look unblinkingly at desperate lives on the margin.

The larger message is perhaps in code. The Iranian cinema, agreed to be one of the most creative in the world today, often makes films about children so that politics seem beside the point, even if they are not. First-time filmmaker Bahman Ghobadi, who wrote and directed this film, may or may not have intended to do anything but tell his simple story, but the buried message argues for the rights of ethnic minorities in Iran and everywhere.

His visual style is documentary. There is little doubt that most of what we see is actually happening, or does happen much as it is represented here. The sight of the mules with two big truck tires lashed to their backs has an intrinsically believable quality.

As for the children, Madi (Mehdi Ekhtiar-Dini) is obviously sadly malformed; there is a touching shot of his eyes peering out apprehensively from beneath the big hood of his coat as he rides in a mule’s saddlebag.

Ameneh is played by Ameneh Ekhtiar-Dini, who has the same last name as Madi, and is probably his sister; I learn from the notes that in general “the villagers play themselves.” I have read about the Kurds being bombed, about the no-fly zone. All merely words, until I saw this movie. Now I will think of little Madi peering out to see what luck he can expect today.