“A Stranger Among Us” sets a love story – or half a love story – in the midst of a murder investigation, and both elements are mishandled. The love story isn’t even supposed to get us steamed up, and anyone familiar with good crime fiction will find the mystery part of the story hopelessly shallow and childish; the solution would not strain Nancy Drew.

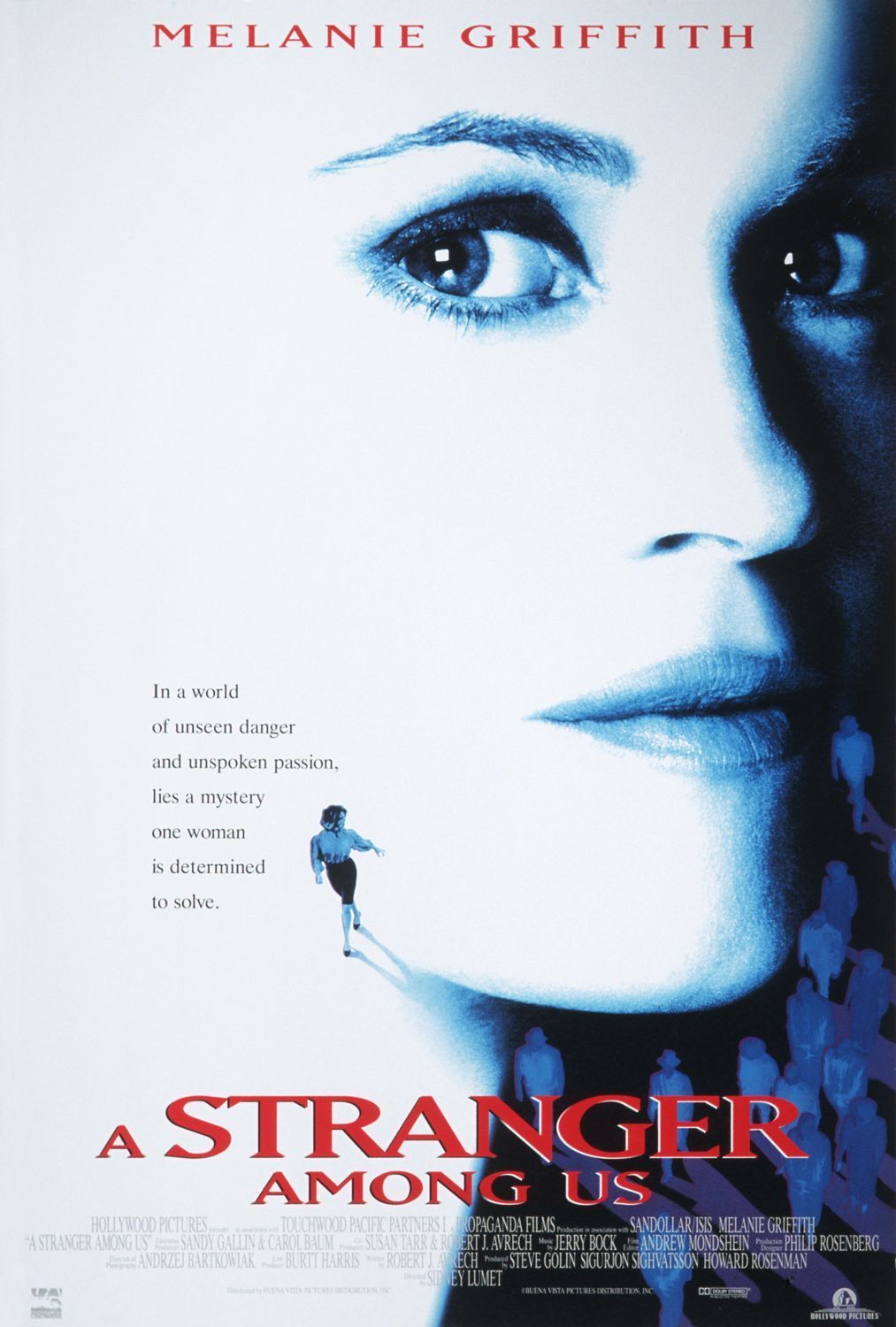

The film stars Melanie Griffith as a New York detective with a reputation for acting first and asking questions later. Assigned to investigate a disappearance connected to a jewel robbery, she finds herself in the middle of a closely knit community of Hassidic Jews.

Did one of them commit the crime? Unthinkable! cries the old rabbi (Lee Richardson). But there are no other suspects, and so Griffith moves into the rabbi’s home. If she lives in the midst of these people, she thinks, she may grow to understand them, and solve the crime.

I doubt the NYPD routinely sends officers to room with possible suspects, but never mind; the movie is obviously setting up the same kind of formula that worked in “Witness” and all of the other fish-out-of-water movies. We know the rules enough to know that the cop will fall in love with one of the members of the community, and, sure enough, Griffith finds herself powerfully attracted to Ariel (Eric Thal), the handsome young student who is destined to be the next leader of the community.

In the version of this movie that played at the Cannes Film Festival in May, that set up a tug-of-war in her heart, because she also had a love affair going with her partner on the force, Nick (Jamey Sheridan), who is wounded in the opening sequence and spends most of the movie in the hospital. “A Stranger Among Us” was not well-received at Cannes, and went to its own cinematic hospital, emerging from surgery with the role of the partner much reduced. This shortened version of the film has a different ending that blots out that other love affair, substituting a life-goes-on exchange between Griffith and another cop.

So what we’re left with is Griffith’s attraction to the young rabbinical student, who patiently explains that a marriage has been arranged for him with the daughter of a French rabbi, and that he must resist the attractions of the flesh, including hers. Since he does so successfully, and since we agree he should, there is no dramatic tension here – just some strained dialogue.

That leaves the crime. And if there has ever been a crime, in all the history of crime movies, that has a lamer solution than this one, I cannot remember it. I will not give away the details, paltry and unsatisfactory as they are. But if you see the film, notice such moments as (a) how Griffith conveniently discovers the body, (b) the gee-wow-golly speech in which she instantly figures out everything, and (c) the clues in the handbag. A high schooler in summer writing workshop could dream up a mys tery more challenging than this one.

Regarding those scenes: Given the blatant clue of those blood stains on the ceiling, what’s surprising is that everyone else on the police force didn’t discover the body before Griffith did. And when she instantly figures out the identity of the criminal, the clues she uses have been available all along. But the screenplay by Robert J. Avrech has her blurt out her reasoning in one lame, awkward speech, so contrived and obvious that it got bad laughs both times I saw the film. Later developments – the opening of the handbag, for example – got more bad laughs.

So. What we have here is a half-witted crime movie, wrapped in one love story that’s a non-starter, and with its other love story consigned to the editing-room floor. Is there anything that can be salvaged? How about the portrait of the Hassidic Jewish community? I dunno.

The movie is shot in a peculiar style, with New York looking bright and clean-edged except for the scenes involving the Hassidic Jews, who live in a different world, filled with dark reds and browns and always in soft focus. When they appear on the screen we get simple-minded music that insists how colorful, quaint and foreign these people are. In the first scene set in their community, Jerry Bock’s music is so inappropriately comical it seems to call for cartoon characters. Theology is limited to greeting-card cliches such as, “God counts the tears of women.” “A Stranger Among Us” was directed by Sidney Lumet, for whom it is an aberration in a usually distinguished career. He has made so many good movies over the years (“Network,” “Dog Day Afternoon,” “The Verdict,” “Running on Empty,” “Q & A”) that I can only assume this project somehow went wrong at the start and he was unable to salvage it. Maybe the original love triangle read well on paper; who knows? What’s impossible to understand is how professional filmmakers could convince themselves that audiences would find the simple-minded crime plot even slightly plausible.