Terence Davies is ever a filmmaker in search of lost time. I do not believe he has ever made a feature film that is set in the present day, unless you count his 2008 documentary on his beloved hometown of Liverpool, “Of Time and the City,” a present day from which he mourned the past. This is not to say that Davies is any kind of nostalgia monger. In gazing at the past, he casts a cold eye on the oppression suffered by his characters, particularly his female ones. See his staggering 2000 adaptation of Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth,” starring Gillian Anderson, a near-surgical dissection of hypocrisy among the New York upper crust at the turn of the 19th century to the 20th. Also his 2011 “The Deep Blue Sea,” filmed from a Terence Rattigan play, in which Rachel Weisz’s Hester is trapped in a loveless marriage in post-World War II Britain.

“A Quiet Passion,” his latest film, goes back further in time than any of his past pictures, to the middle of the 19th century, and returns him to America, a place he has now visited three times in his filmography. (His 1995 film of John Kennedy Toole’s novel “The Neon Bible” was set in 1940s Georgia.) Working from his own original screenplay, “A Quiet Passion” treats the life and the work of the poet Emily Dickinson, whose vast body of work was mostly unpublished in her lifetime. The movie begins with young Emily (played by Emma Bell) keeping still in the middle of a chairless schoolroom as her fellow students move to the left or to the right, following the instructive questioning of a teacher who asks in just what way they desire to “come to God and be saved.” Standing in the middle of the room Emily tells her teacher, “I am not even awakened yet.” Therefore, she asks, “How may I repent?”

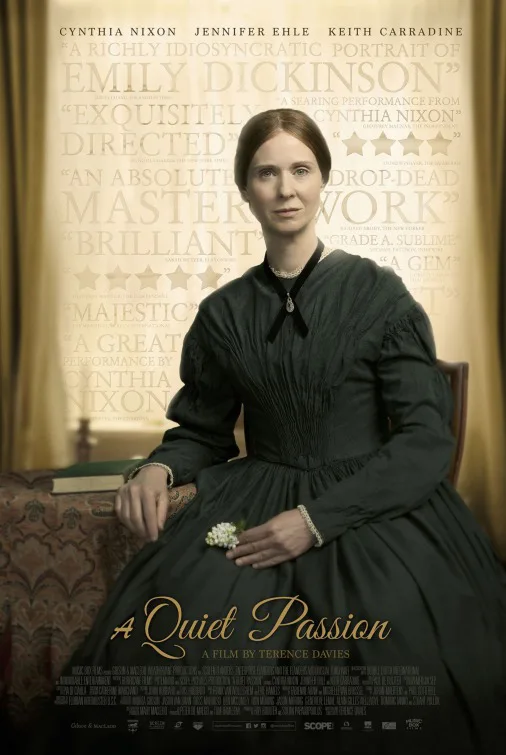

We learn a little about how Emily acquired such seeming impudence. Her father, Edward, portrayed with solemnity and an unavoidable touch of wryness by Keith Carradine, is a lawyer with liberal proclivities and possessed of some religious skepticism, not exactly an au courant view in Amherst polite society. That said, he is also quite conventional in his views of women and their place, albeit surprisingly indulgent of his children at times. At supper with the now-adult Emily, played by Cynthia Nixon, he complains of a plate being dirty. Nonplussed, Emily picks up the plate and drops it to the floor, letting it shatter. She tells dad it is not dirty anymore. He actually seems amused.

The days of Amherst go by uneventfully enough at first. Emily whiles away the hours with her younger sister Vinnie (Jennifer Ehle) and best friend Vryling Buffam (Catherine Bailey). They stroll through gardens and go to teas and trade quips. Emily publishes a scant poem or two in a local journal run by a friend of her fathers. There are suitors and marriages—for others. Emily is too outspoken, too disinterested, too Emily to do anything but be herself. And to write, mostly in secret. Davies does not view Dickinson as any kind of eccentric. Indeed, one feels that Davies strongly identifies with her. His dedication to his portrait is spectacularly evident in every shot of this very unusual movie. At first he presents his story and characters in the form of tableaus, like something out of a silent picture. The characters speak stiffly and stand as if posing. As the movie continues, and certain events that came to define America and its character—particularly the Civil War—touch the lives of the Dickinsons, and we hear more of Emily’s work in voiceover, the movie’s style becomes less constricted, more fluid, but still retains an unearthly quality. Just as Dickinson’s poetic mode of personal expression and ear for idiosyncratic metaphor anticipated modernism, so here does Davies’ cinematic style slip certain bonds and achieve an unquiet fluidity. The effect is remarkable.

And it is grounded, and made most exemplary, by Cynthia Nixon’s performance. Every actor in this movie is wonderful. But Nixon’s precision in portraying every particular mood of Emily—for each individual scene calls for absolute specificity—is simply spectacular. There are points in Emily’s life when she is racked by illness, or possessed by a seeming madness. Her fury at the misbehavior of a family member in one scene late in the film, as she rails against a perceived lack of integrity, is chilling because Nixon makes the viewer see the extent to which Emily is actually turning that rage back upon herself. Every scene in the movie contains a performance revelation of almost equal power. I will be very surprised if I see a better performance from an American actor this year.

“A Quiet Passion” is not suffused with the romantic ache or agony of some of Davies’ other films. It does not mourn for what Emily Dickinson did not have. Rather it admires her for what she was, and what literary posterity made of her. And it invites the viewer to take seriously her mode of thought and of art; not just to take seriously, but to revel, inasmuch as one is able to revel in work that is simultaneously so austere and so rich. Like the movie itself.