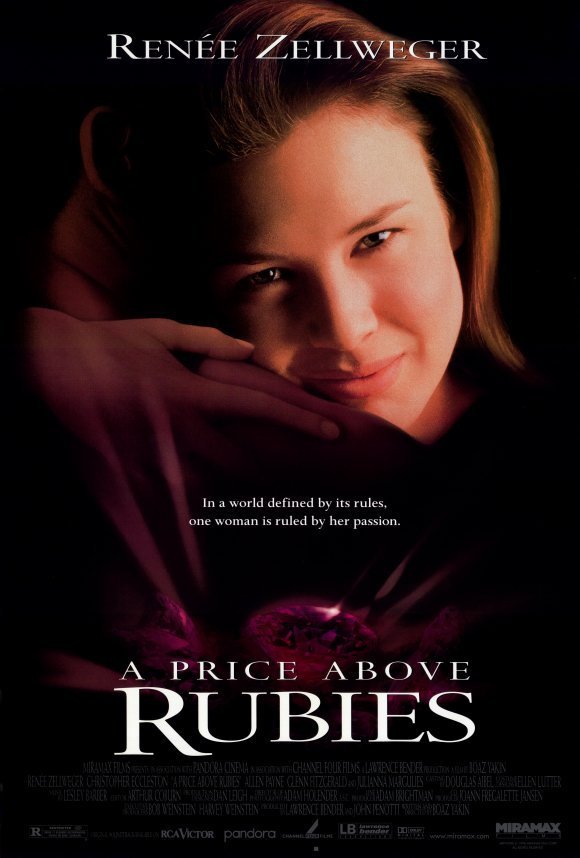

“A Price Above Rubies” tells the story of a woman who burns for release from the strictures of a closed society. We learn much about her during the film, but not much about her society–a community of Orthodox Hasidic Jews, living in Brooklyn. Perhaps that’s in the nature of commercial filmmaking; there is a larger audience for a story about the liberation of proud, stubborn Renee Zellweger (from “Jerry Maguire“) than there is for a story about why a woman’s place is in the home.

During the film, however, questions about the message were not foremost in my mind. I was won over by Zellweger’s ferociously strong performance, and by characters and scenes I hadn’t seen before: the world, for example, of Manhattan diamond merchants, and the parallel world of secret (untaxed) jewel shops in Brooklyn apartments, and the life of a young Puerto Rican who is a talented jewelry designer. The film also adds a level of magic realism in the character of an old homeless woman who may be “as old as God himself.” Zellweger plays Sonia, the daughter of gemologists who steer her away from the family business and into an arranged marriage with a young scholar named Mendel (Glenn Fitzgerald), who prefers prayer and study to the company of his wife. (During sex, he turns off the light and thinks of Abraham and Isaac.) Sonia’s unhappiness makes her an emotional time bomb, and it is Mendel’s older brother Sender (Christopher Eccleston) who sets her off. First, he tests her knowledge of jewelry. Then, he offers her a job in his business. Then, he has sex with her. It’s rape, but she seems to accept it as the price of freedom.

“A Price Above Rubies” is the second film by writer-director Boaz Yakin, whose “Fresh” (1994) was able to see clearly inside an African-American community; here, although he is Jewish, he is not able to bring the Hasidim into the same focus. All I learned for sure about them is that the men wear beards and black hats and suits, and govern every detail of daily life according to the teachings of rabbis and scholars. The women obey their fathers and husbands, and the group as a whole shuns the customs of the greater world and lives within walls of rules and traditions. There is not a lot of room for compromise or accommodation in their teachings, which is a point of tension in modern Israel between Orthodox and other Jews.

Sonia does not find this a world she can live in. She is rebellious when her husband insists their son be named after the rabbi, rather than after Sonia’s beloved brother, who drowned when he was young. She is opposed to the boy’s circumcision (“he’s like a sacrifice!”)–but, to be sure, her husband also faints at the sight of blood. She is as resentful of Mendel’s long hours at study and prayer as another wife might be toward a husband who spent all of his time in a bar or at the track. And there is that unquenched passion burning inside of her. (In equating her sexual feelings with heat, Yakin unwittingly mirrors the convention in porno films, in which women complain of feeling “hot … so hot” and sex apparently works like air conditioning.) After her brother-in-law sets her up in the jewelry business, she glories in her freedom. She wheels and deals with the jewelry merchants of the city. On a park bench one day, she sees a black woman with beautiful earrings, and this sends her on a search for their maker, Ramon (Allen Payne), a Puerto Rican who sells schlock in Manhattan to make money, and then does his own work for love.

This man is unlike any Sonia has ever met, but at first her love is confined to his jewelry. She encourages him, commissions him, reassures him that his work is special. But then Sender discovers their connection and tells Sonia’s husband and family, and Sonia is locked out of her house, cut off from her child, and divorced.

It is hard to see why Sender would take that risk, considering what a powerful weapon Sonia has: She could accuse him of rape. But perhaps he knows she wouldn’t be believed. His values are hardly those of his prayerful brother’s; he believes we sin in order to gain God’s forgiveness (or perhaps even his attention), and that “the quality of our sins sets us apart.” I was always completely absorbed in Sonia’s quest. Zellweger avoids all the cute mannerisms that made her so lovable in “Jerry Maguire,” and plays this young woman as quiet, inward, even a little stooped. She knows she must find a different kind of life for herself, and does.

The film has been protested by some Hasidic Jews, who especially disliked the circumcision scene. Yakin did little for his defense by claiming it was “comedic”–which it is not remotely. Like the Amish of “Kingpin” and the Catholics of the early scenes in “Household Saints,” these Jews come across as exotic outsiders and holdouts in the great secularized American melting pot. What may offend them as much as anything is that their community is reduced to a backdrop and props for Sonia’s story. It would be an interesting challenge for a filmmaker to tell a story from inside such a community. “Witness” came close to suggesting the values of the Amish, I think, but then how would I really know?